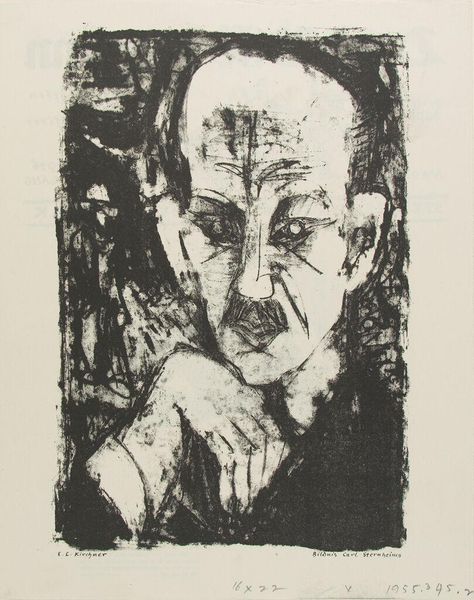

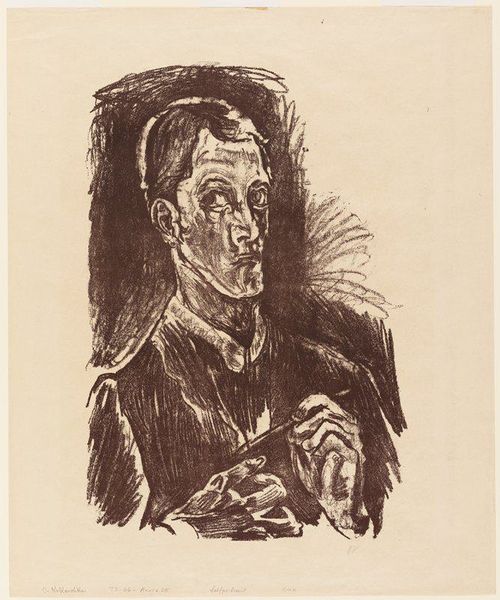

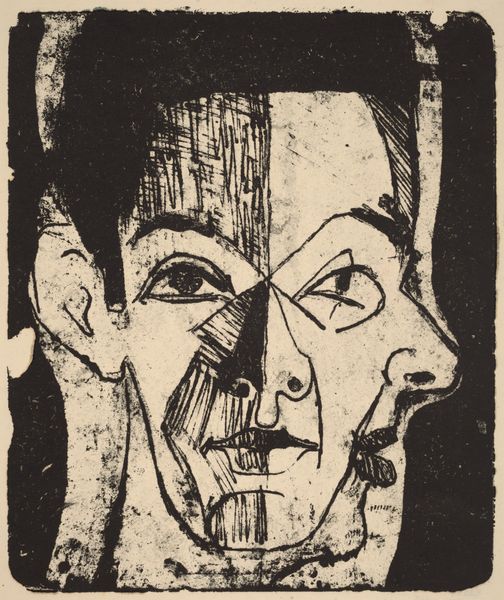

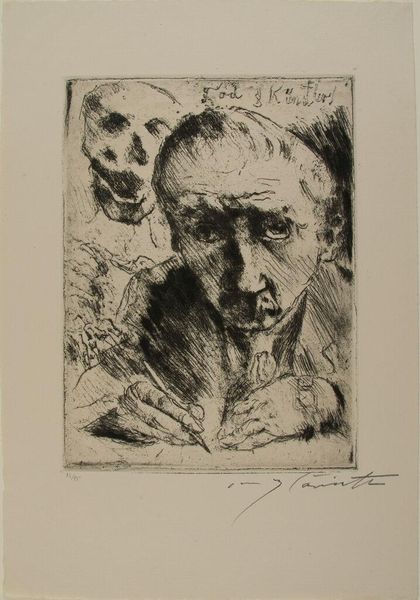

lithograph, print, ink

#

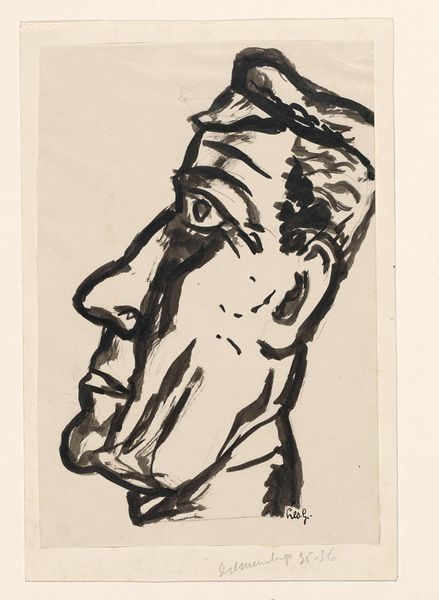

portrait

#

germany

#

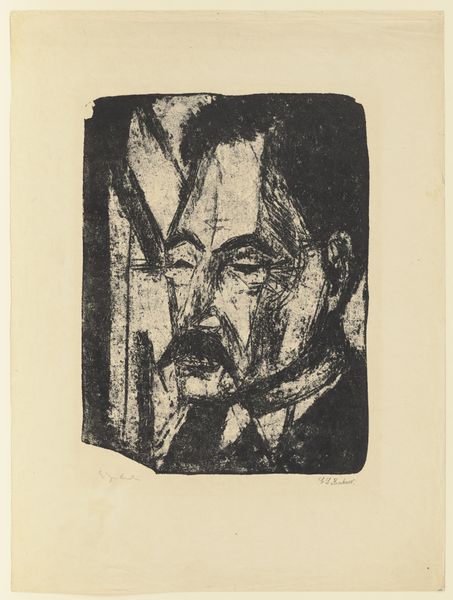

lithograph

# print

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

ink

#

tattoo art

#

monochrome

Dimensions: 13 13/16 x 10 13/16 in. (35.08 x 27.46 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

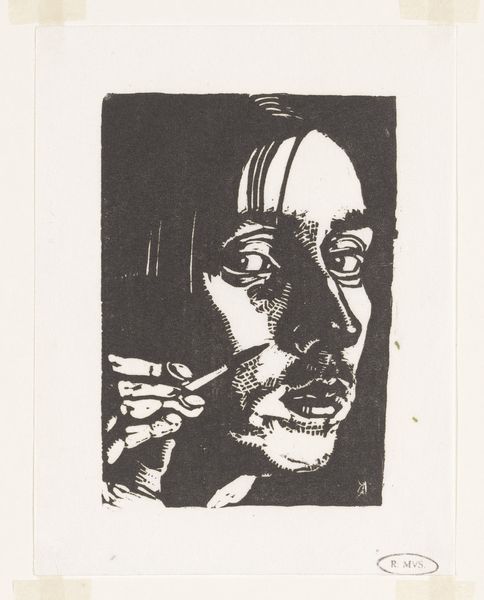

Curator: Looking at Kirchner’s "Portrait of Carl Sternheim," a lithograph from 1916 now residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I'm immediately struck by the stark contrast and intensity of emotion it conveys. Editor: The harsh, almost brutal, lines give it such a sense of unease. It's unsettling, yet compelling. I keep wanting to look away, but something holds me captive. Curator: Those lines are incredibly symbolic in German Expressionism. Artists often used distorted features to depict inner turmoil. Here, the monochrome palette emphasizes Sternheim’s somber gaze and thoughtful pose. There's a certain darkness, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Absolutely. Consider the historical context: 1916. World War I raged, profoundly impacting German society and art. The sense of disillusionment and psychological trauma permeates much of the Expressionist work produced during that period, shaping how we, even now, interpret it. This is more than just a likeness. Curator: Precisely. Kirchner saw Sternheim—a playwright—as part of an avant-garde artistic circle, a patron almost. This image becomes an icon then, for their cultural moment: the Weimar Republic, the cultural shift that marked modernity itself. Editor: But, as with all portraits, there's the power dynamic. Artist and sitter. Patron and creator. How much control did Sternheim have over his own image, his own representation for posterity, especially within this tumultuous era? The very act of creating a print – designed for circulation – places it firmly within the arena of public perception and potentially political discourse. Curator: And I’m sure those spiky, almost aggressive strokes felt revolutionary in the day; now, we know how much psychological weight Kirchner was able to load onto simple monochrome portraiture using these marks. The stark symbolism is very striking, don’t you agree? It becomes almost emblematic of the era’s anxiety and creative intensity. Editor: Thinking about how art reflects—and refracts—society is endlessly rewarding. Curator: Absolutely, providing insight through symbolic representations of internal struggles.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938) was a leading artist of the German Expressionist movement of the early twentieth century. A painter, sculptor, and graphic artist, Kirchner, along with fellow artists Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, helped found "Die Brücke" (The Bridge), a loose association of avant-garde German and Austrian artists formed in 1905 in reaction to the prevailing academic traditions of German art. The group’s manifesto underscored its commitment to the unrestricted freedom of artistic expression. Its collective style was characterized by bold colors, semi-abstraction, violent imagery, and emotionally evocative subject matter. Later members of the group included Otto Mueller, Emile Nolde, and Max Pechstein. Although "Die Brücke" disbanded in 1913, its principles and activities continued to fuel Expressionism as a driving force in the evolution of modern art, and for several years Kirchner took its trajectory to new extremes. Carl Sternheim (1878–1942) was a prominent German playwright and satirist and leading proponent of German Expressionism. He founded the Expressionist literary journal "Hyperion." The Nazi government banned Sternheim’s plays and short stories after coming to power in 1933 because of his attacks on the moral failings of the German middle class. A friend and longtime patron of the artist, Sternheim sat for his portrait during a period when Kirchner was recovering from a mental breakdown brought about by the horrors of warfare he witnessed while serving as an infantry soldier in the German Army in 1914 and 1915.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.