drawing, paper, ink

#

architectural sketch

#

landscape illustration sketch

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

mechanical pen drawing

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

cityscape

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

initial sketch

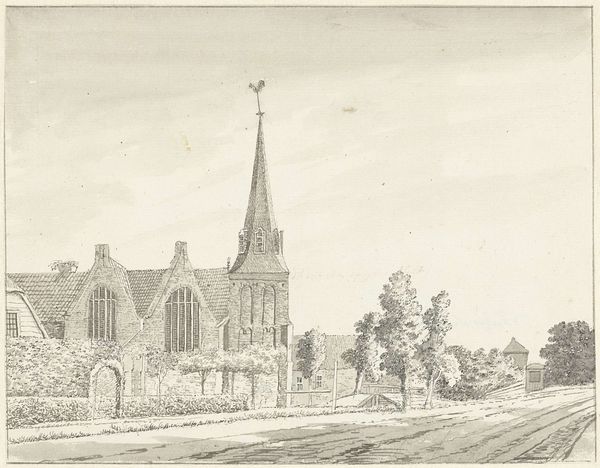

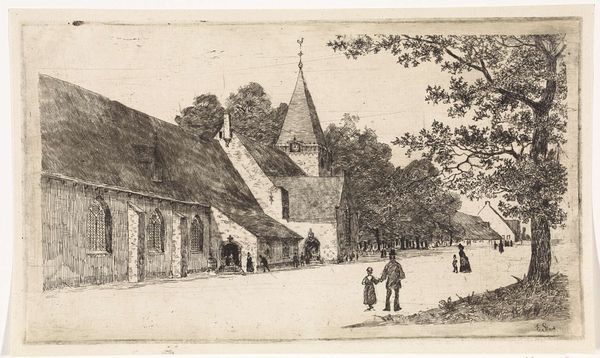

Dimensions: height 133 mm, width 172 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Cornelis Pronk's "Achterste deel van de Grote kerk te Edam," or "Rear view of the Great Church at Edam," created in 1727. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's remarkably detailed for what looks like a quick sketch! I mean, there's a lightness to it, but those architectural details, rendered in ink… it feels both spontaneous and incredibly precise. Curator: Precisely! Pronk was a master draughtsman, renowned for his topographical drawings. He'd meticulously document buildings and landscapes. You can see the architectural specificity – every window, every stone feels accounted for. But there's also an artistic looseness, a sketch-like quality in the trees surrounding the church that softens the structure itself. Editor: I'm fascinated by the material constraints he faced. Think about the paper, the ink available at the time. And the sheer skill required to achieve such delicate lines and shading with just a pen. It’s a directness that speaks volumes about the craft of image-making. Did Pronk use these sketches simply for topographical purposes or were these also sold as individual artworks? Curator: He probably used them as source material for larger, more elaborate commissions. Though these sketches themselves are certainly appreciated for their artistic merit now! To me, it feels like he's capturing not just the church, but a moment in time – the people strolling by, the light filtering through the trees... a fleeting atmosphere, really. There is a stillness, like he has found the perfect quiet observation point. Editor: Exactly! It brings up interesting questions about the function of art, especially in an era defined by merchant culture. Was it primarily documentation, a means of recording place and history for practical reasons? Or could the craft elevate something beyond the purely utilitarian to be collectible for personal appreciation? Maybe the better question is simply why not both. Curator: And that's precisely where its beauty lies, I think. It blurs the line between documentation and artistic expression. Editor: I appreciate the look 'behind the scenes.' It’s easy to imagine the artist working, finding his spot, preparing for his masterpiece. Thanks for walking us through the view. Curator: My pleasure! There’s a humble grandeur that invites us to see the beauty in the everyday, which I always appreciate.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.