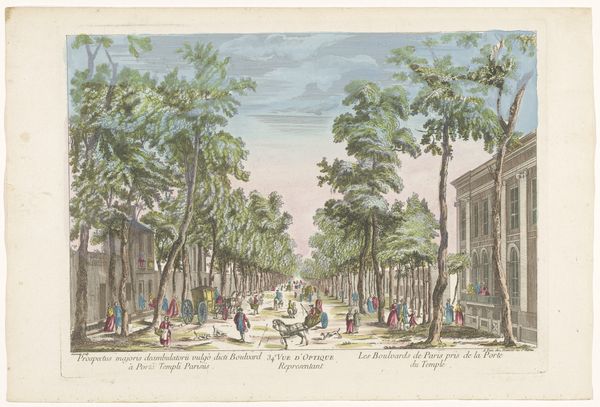

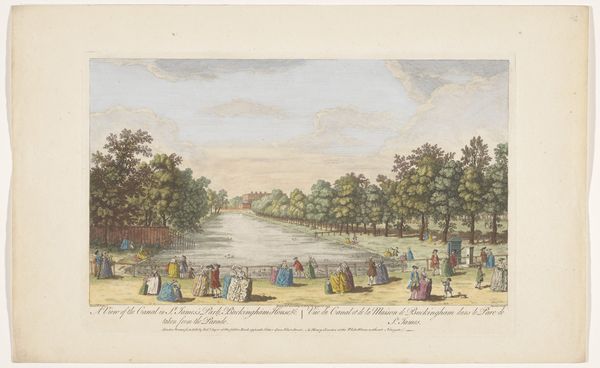

Gezicht op een boulevard te Parijs gezien vanaf de Porte Saint-Antoine c. 1759 - 1796

0:00

0:00

louisjosephmondhare

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 388 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Gezicht op een boulevard te Parijs gezien vanaf de Porte Saint-Antoine," or "View of a boulevard in Paris seen from the Porte Saint-Antoine" by Louis-Joseph Mondhare. It’s an aquatint from around 1759-1796, located here at the Rijksmuseum. The colors are delicate, and the scene is bustling with carriages and figures. What strikes you about it? Curator: What interests me is the material process behind this image and its context. Aquatint, as a printmaking method, democratized image production. Before this, who had access to depictions of Paris? What kind of labour went into making this image reproducible, and who consumed it? Was it accessible only to the wealthy elite who also occupied those boulevards, or did it allow others a glimpse into that world? Editor: That's interesting; I hadn’t considered the accessibility aspect. So the value lies not just in the aesthetic but in the shift it represents in how images were disseminated? Curator: Precisely. Consider the physical effort to create the copper plate, the specialized knowledge required for the aquatint process, the paper used. It all speaks to the means of production and the networks of artisans and consumers necessary to bring this image into being. Is this not Rococo being consumed? Editor: Right, like a material record of a specific social and economic moment. Before, I saw it as just a pretty scene, but thinking about it as a product changes my perspective. Thanks. Curator: And by thinking about its materiality, we realize it is less "a pretty scene" and more a produced artifact – connected to labor, class, and the rise of consumerism. It changes the questions we ask of it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.