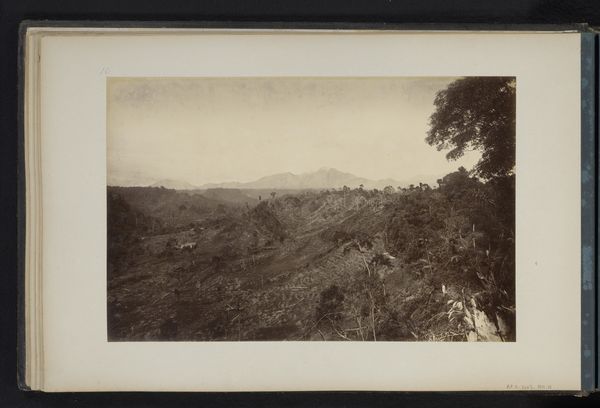

photography, albumen-print

landscape

indigenism

photography

orientalism

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 242 mm, width 367 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

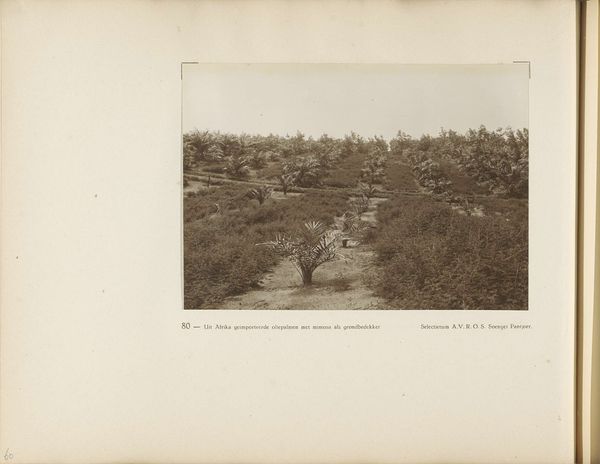

Editor: We’re looking at "Gezicht op de Gambir plantage, Sumatra," a photograph, an albumen print, by Heinrich Ernst & Co, dating to around 1890-1900. It depicts a plantation scene, very lush, almost overwhelmingly so. There's a clear tension between the wildness of the landscape and what I assume is the cultivated plantation. How do you interpret this work, especially considering its historical context? Curator: Well, it's impossible to view this photograph outside the context of Dutch colonial expansion. These idyllic-looking plantation scenes were tools in promoting the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, as a lucrative and manageable territory. Notice the framing; the photographer positions the viewer as outside observers, looking "down" on the plantation. Do you think this impacts our perception? Editor: Absolutely. There's a sense of detachment, of distance. It feels staged, a presentation of a "productive" landscape to potential investors, maybe? Not a raw, documentary style image. Curator: Precisely. The "picturesque" framing reinforces that detachment and romanticizes a system built upon exploitation and forced labor. Albumen prints like this were popular for their sharp detail and warm tones, ideal for selling an exotic but controlled image of the colony back home. This is Orientalism at play, reducing a complex reality to palatable, consumable imagery. Editor: So it's not just a pretty picture, but a carefully constructed message about colonial power? Curator: Exactly. These photographs were rarely about objective truth. They were about shaping perceptions and legitimizing a particular social and political order. And the distribution of these images, their display in exhibitions, magazines – it all solidified that colonial gaze. Editor: That gives me a whole new perspective. I came in seeing a landscape, but now I see a form of propaganda. Curator: It’s a reminder that art, especially art from this period, requires critical engagement with its historical and political implications. Images can be very persuasive, even when seemingly straightforward.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.