Rozen met silhouetportretten van Willem I Frederik, koning der Nederlanden, Wilhelmina van Pruisen, hun kinderen, zijn ouders en zijn zus 1815 - 1819

0:00

0:00

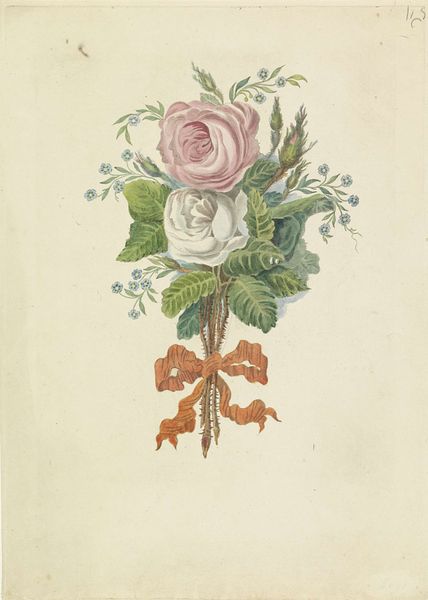

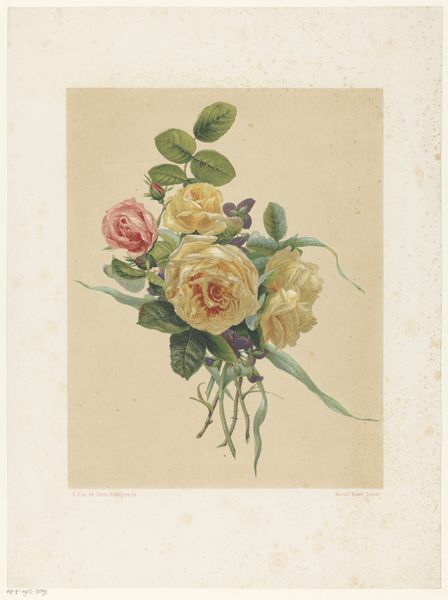

drawing, watercolor

#

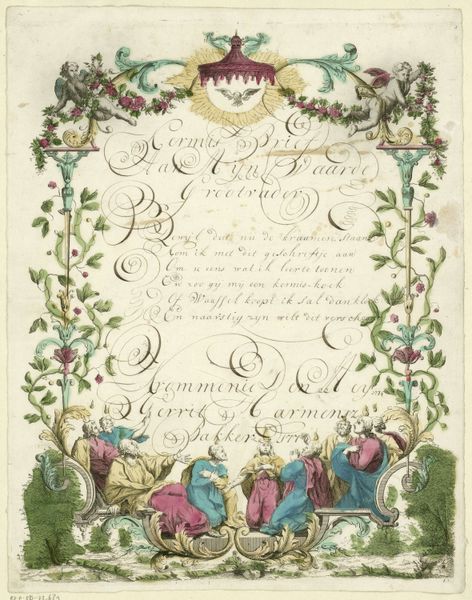

drawing

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

botanical drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 327 mm, width 226 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Roses with Silhouette Portraits of Willem I Frederick, King of the Netherlands, Wilhelmina of Prussia, their Children, his Parents and his Sister" created between 1815 and 1819 by Leonardus Schweickhardt. It's a delicate drawing primarily done with watercolor. Editor: Immediately, the formality of the portraits contrasts with the gentle medium and floral arrangement. It's saccharine, almost overwhelmingly sweet at first glance. Curator: Indeed, but let's consider the materiality of watercolor at this time. It's portable, relatively inexpensive, and readily accessible, suggesting a wider audience and perhaps a democratization of royal portraiture. Furthermore, botanical drawings were not just artistic pursuits, they were linked to scientific documentation and the expansion of global trade. What’s being consumed here? Editor: A carefully crafted image of domesticity and power, of course. This botanical illustration is more than just pretty flowers; it's a carefully constructed visual symbol intended to legitimize and normalize the reign of Willem I after a period of immense social and political upheaval, reminding the population about royalty. Those silhouette portraits worked into the floral design serve as reminders of the people behind the crown. Curator: And think of the labor involved, both visible and invisible. Schweickhardt likely worked on commission, a transaction involving money and a particular skill set. Also, the production and distribution of watercolors themselves relied on networks of trade and colonial exploitation, accessing pigments from across the globe. Editor: The orange ribbon and the inscription also gesture towards the House of Orange-Nassau, with the use of symbolism being a key element. Consider this artwork’s viewers. What impact do you suppose it had during its period? Were the families that possessed such works royalists by chance, or were they sympathetic with other societal perspectives? Curator: That intersection of art and manufacturing invites a rich investigation into consumption patterns, patronage, and the role of visual media in shaping cultural identity during the rise of nation-states. The image’s reproduction enabled its dissemination. Editor: Absolutely, I see it as a powerful, almost propagandistic, representation of royal stability and a reclaiming of national identity through carefully chosen iconography and portraiture. Curator: Thinking about the networks involved helps understand not only its function as visual material but also its relationship to labour, industrial networks, and the social economy of the time. Editor: Viewing it through the lenses of both artistic expression and the larger historical context offers a far more nuanced understanding than simply admiring the watercolor technique.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.