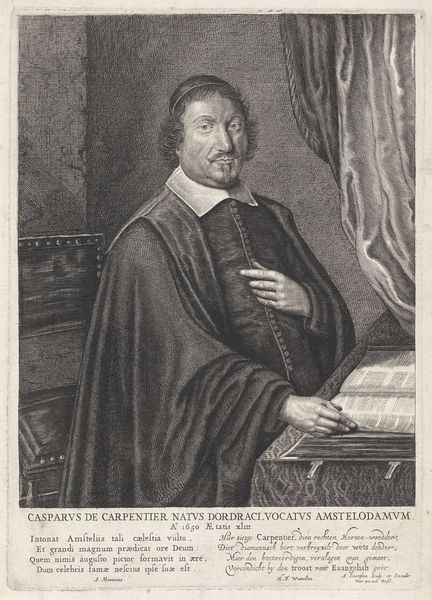

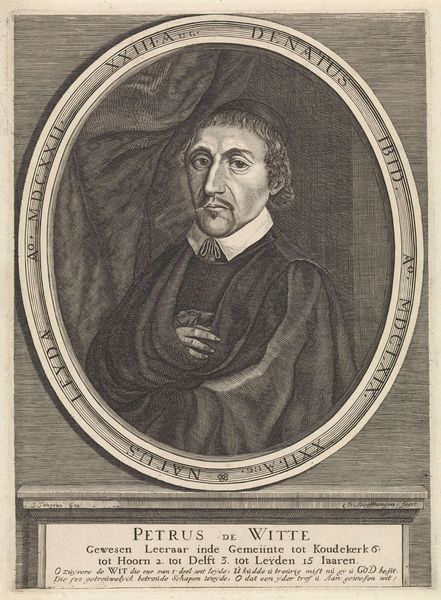

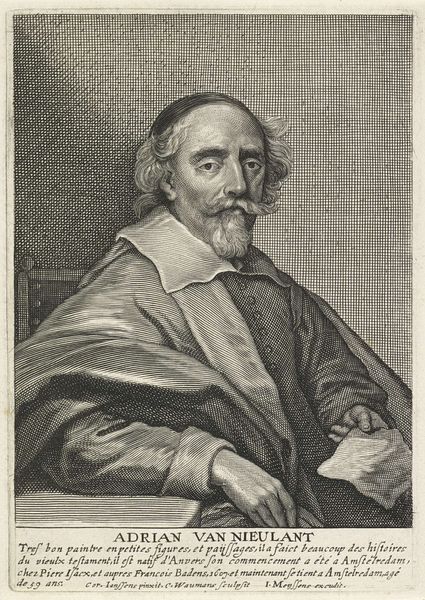

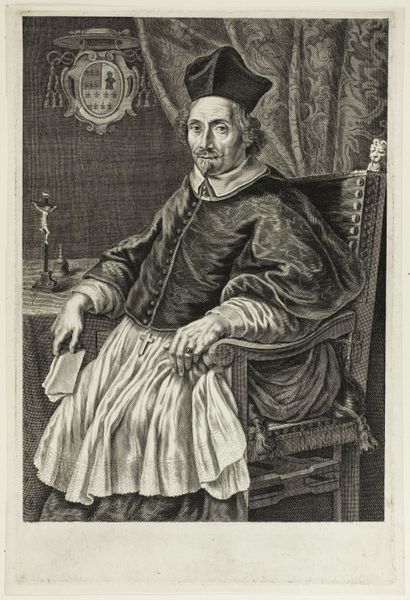

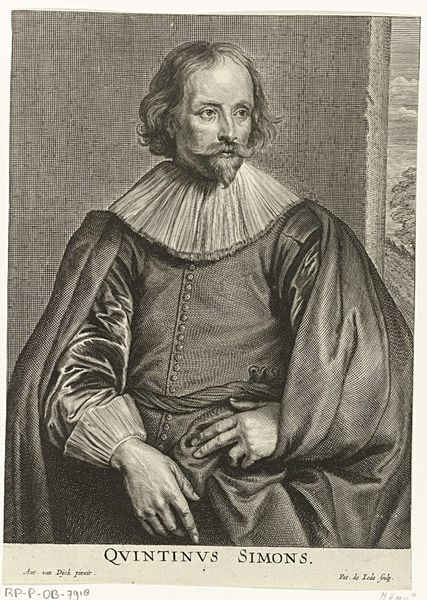

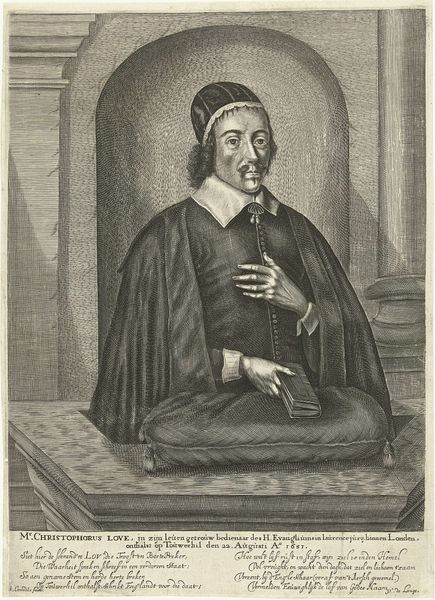

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

portrait reference

#

animal drawing portrait

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

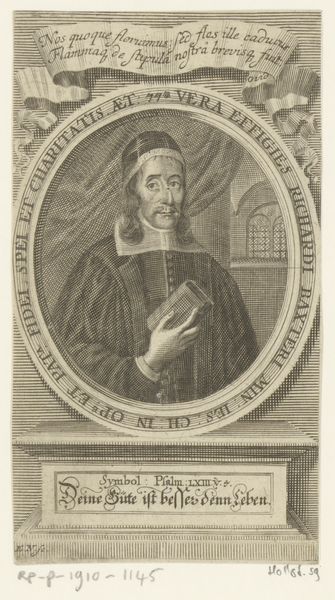

Dimensions: height 142 mm, width 88 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The somberness is striking, isn’t it? Almost a feeling of restrained melancholy. Editor: It is indeed. What we have here is a portrait, an engraving executed sometime between 1651 and 1652. The inscription identifies the sitter as Christopher Love, and the engraver as A. Conradus. Curator: The level of detail achieved through engraving is remarkable, look at the meticulous rendering of his garments. It brings to mind questions of artisanal skill, apprenticeship systems, the engraver's studio. What was the relationship between Love, the sitter, and Conradus, the man who made this image? Was it commissioned, and if so, by whom and at what price? Editor: He seems to hold himself with an almost priest-like gravitas, doesn’t he? The hand placed just so upon his chest; a symbolic gesture of piety, of holding something sacred close to the heart, perhaps? Curator: Yes, the act of bearing witness, which is visually underscored by his book, held as an object, reminds me about the means of early book production that makes literary culture available for all. In some way it makes Christopher Love a physical medium for carrying text forward in history, and available to audiences as consumers. Editor: Consider also the background. A simple yet solid column is only partially visible, implying steadfastness. The gridded texture feels almost like a wall; together, these lend the sitter an air of being enclosed. Perhaps mirroring, even subtly reinforcing, his devotion to his faith amid possible societal turbulence. It creates a fascinating tension between internal faith and external constraints. Curator: Such portraits functioned within very specific circuits of economic and symbolic exchange. How did they negotiate notions of status, power, and even religious conviction in their own time, and what do they tell us about shifting systems of value? This engraving in its reproducibility could easily move among spaces of the Protestant movement at the time of political turmoil and civil wars, circulating among different audiences of the text itself. Editor: It makes you consider what endures. While we may never know the specifics of this commission, Love’s portrait resonates because certain visual languages, especially those around faith, have a remarkable continuity. Even now, that careful hand placement carries significant weight. Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about it now, the historical implications are even more present than before, considering that the artist was dealing with an icon in his own time. Editor: An icon then, viewed today as both a relic and a work of enduring symbolism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.