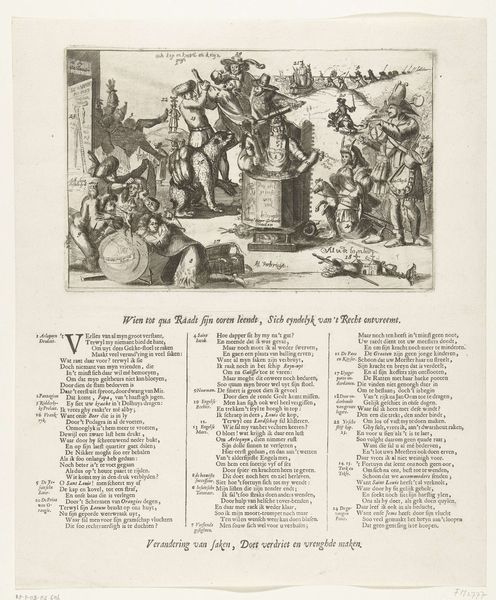

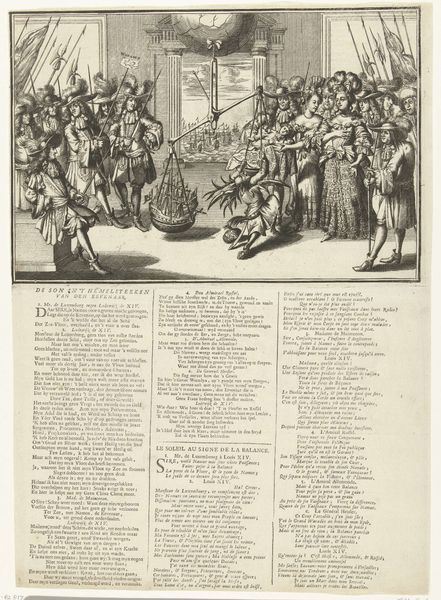

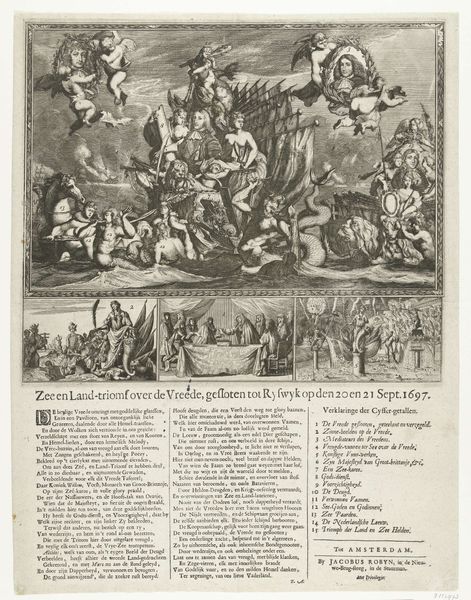

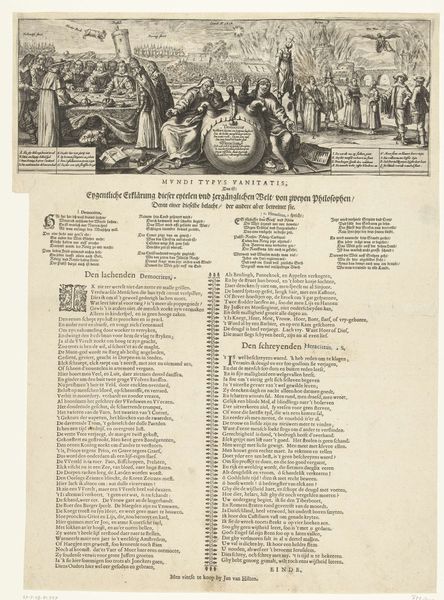

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

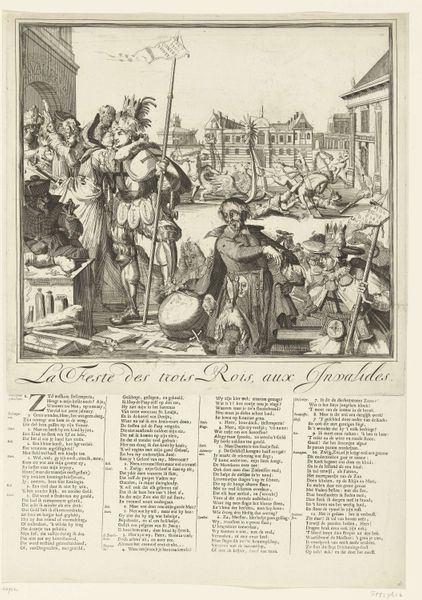

graphic-art

#

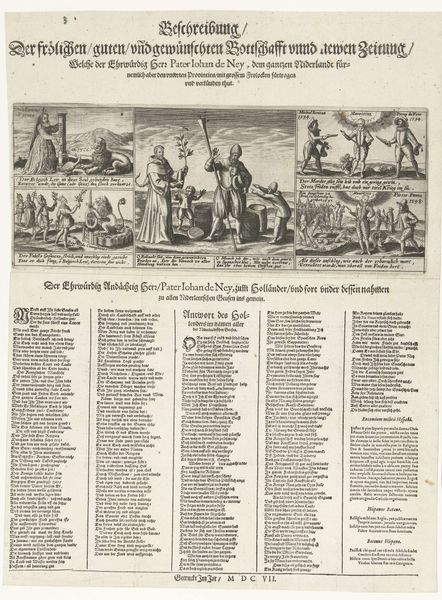

allegory

# print

#

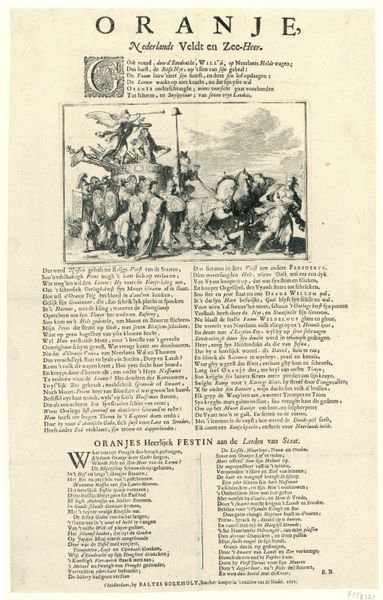

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 398 mm, width 311 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Spotprent op de Vrede van Utrecht", a print made in 1713 by Abraham Allard. It's brimming with figures and symbolism, and honestly, it’s a little overwhelming at first glance. There's so much going on. What can you make of it? Curator: It’s indeed quite dense. From a historical perspective, this print functions as a piece of political commentary. The Peace of Utrecht, which it depicts, was a series of treaties that ended the War of the Spanish Succession. The artist, Abraham Allard, uses allegory to express a particular viewpoint on the political climate of the time, likely criticizing the terms of the peace. Notice how certain figures are emphasized while others are marginalized. Consider who benefits and who suffers in this representation. Editor: So, the arrangement of the figures isn't just decorative; it's a way of conveying political messages about power dynamics. The composition directs us to feel sympathetic towards specific groups, is that right? Curator: Precisely. Ask yourself, who are these 'peace-loving heads' arriving in Utrecht, as the title suggests? What are their motivations and agendas? Are they truly bringing peace, or are there ulterior motives at play? Also, how are women represented in the piece? Do their roles signify anything about the socio-political expectations of the time? Editor: That makes me wonder about the specific symbols used. Are there any visual cues that would have been particularly meaningful to audiences back then, but might be lost on us today? The dog for example. Curator: Yes, the dog is likely meant to represent fidelity. Considering the image as a whole, what are those figures loyal to? Were the represented actions seen as faithful to certain ideals or leaders, or did they signal a betrayal? Understanding these symbols reveals the print as more than just a historical record but also an argument. Editor: I hadn't considered how loaded an image like this could be. Thanks for pointing out all the subtle details; it’s much clearer now that it's more about contemporary political dialogue and critique than just peace. Curator: Exactly, we can read the print now as an intervention in the making of history. It makes you think about the role images play in shaping public opinion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.