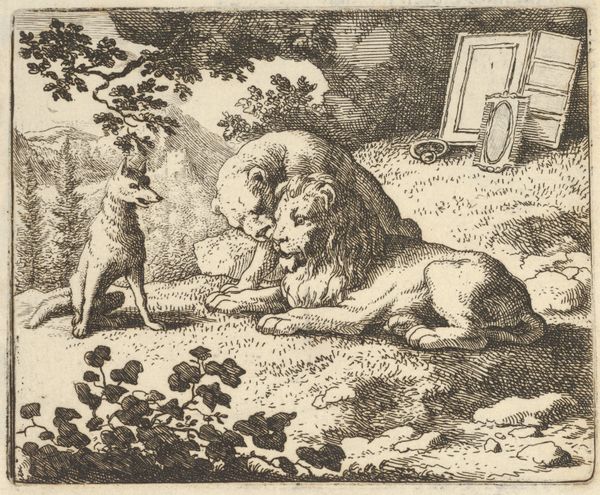

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 226 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me most immediately about this pen and ink drawing from 1664 titled, "Liggende leeuw de staart op de voorgrond" or "Lying lion with tail in the foreground," by Marcus de Bye, currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum, is its languid strength. The lion seems utterly relaxed, yet the detailed musculature speaks to underlying power. Editor: Yes, it's a surprisingly intimate portrayal for an animal often used as a symbol of royalty and power. The lion reclines almost contemplatively. What are the contexts that informed de Bye’s rendering of this powerful animal? Was it simply a study of form, or something more symbolic? Curator: It’s intriguing, isn't it? Lions in art of this era frequently signified dominion and courage, concepts intrinsically tied to the colonial endeavors and aristocratic identity construction prevalent in the 17th century. The lion as king of beasts becomes a potent symbol in European imagery, a testament to a self-fashioned, entitled worldview. Editor: And looking at it now, one cannot separate those layers from the immediate experience of seeing this regal beast. There’s a deliberate placement of the tail— in the foreground— almost as if emphasizing the tangible, the here and now of the lion’s presence. That disrupts any potential glorification; it’s a grounded perspective. Curator: Absolutely. Moreover, the seemingly untouched landscape in the background contrasts sharply with the presence of a single predator; the vastness mirrors, perhaps, a potential for expansionist dominance or echoes the wilderness tamed under its regal figure, all framed in the artist's intent and broader socio-political frameworks. The implications run deep. Editor: Indeed. Looking at the image now, with this context, I recognize its potency in carrying colonial undertones. I notice, as well, how it offers opportunities to explore shifting societal perspectives on animals and representation as cultural constructs laden with complex significance. I appreciate, however, how our contemporary viewing forces engagement with its multifaceted visual history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.