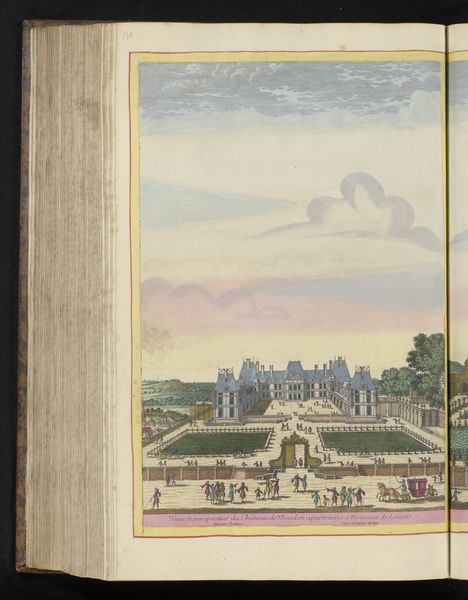

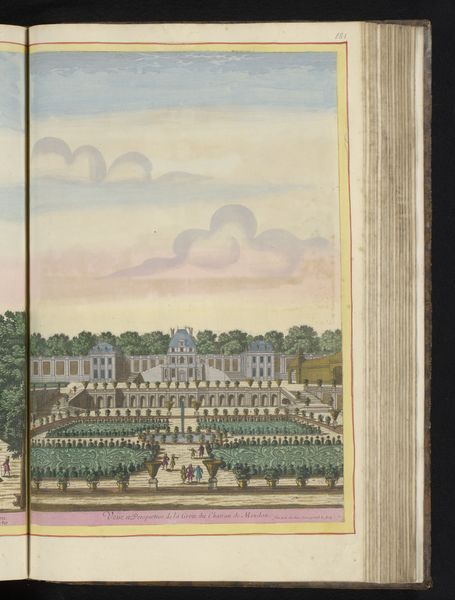

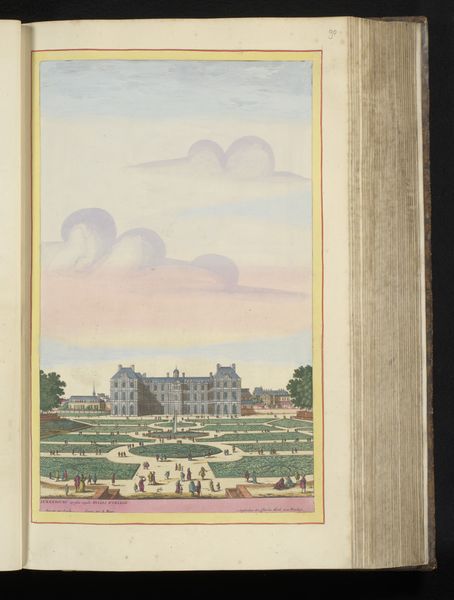

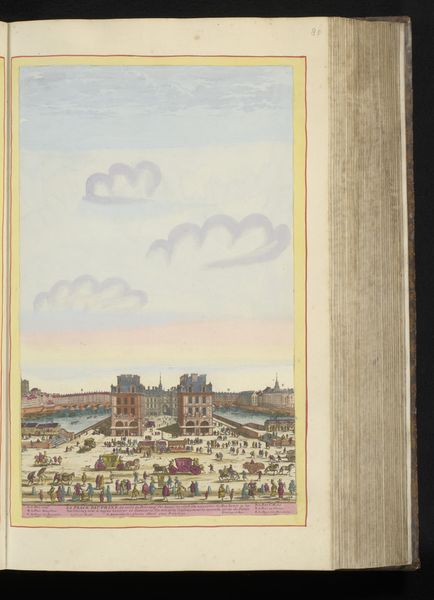

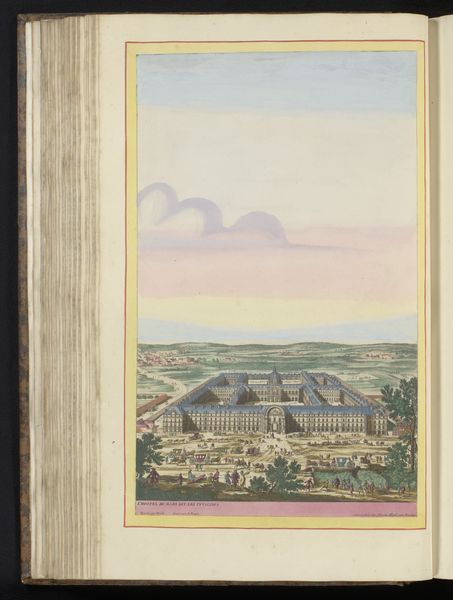

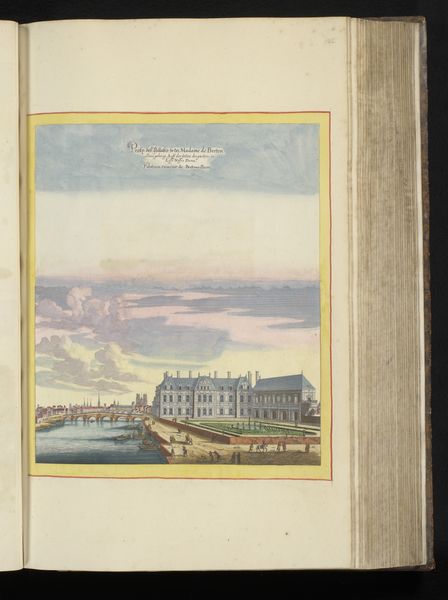

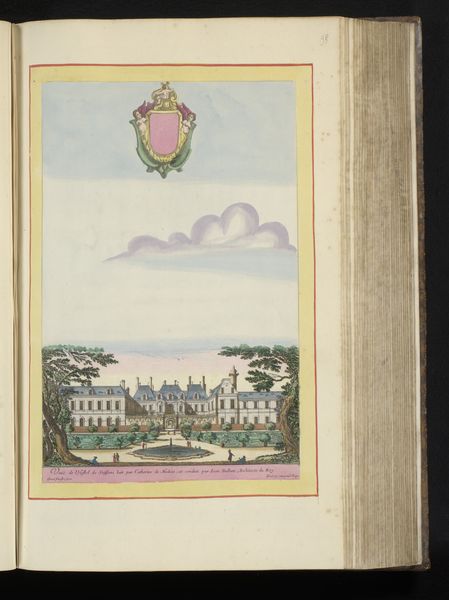

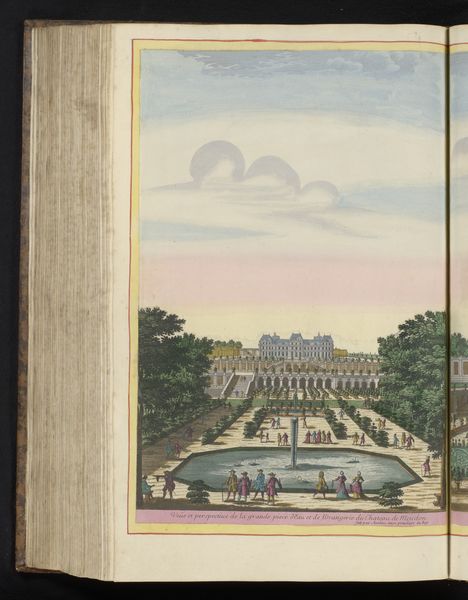

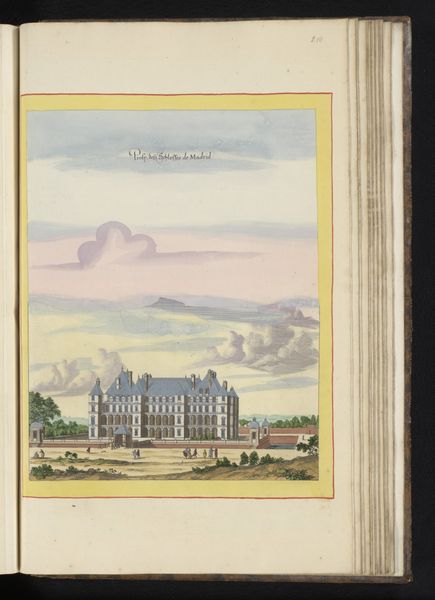

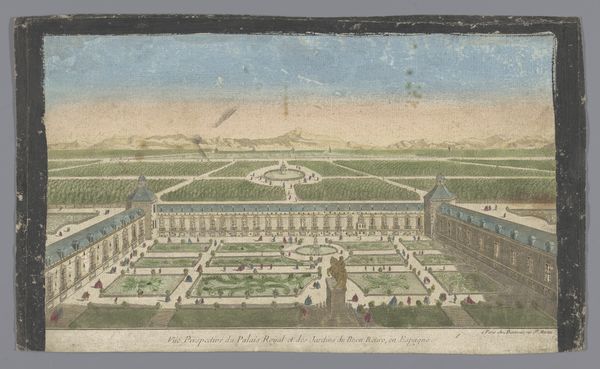

drawing, coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

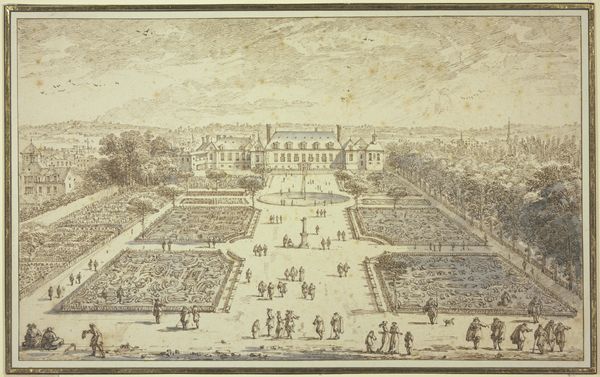

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 440 mm, width 309 mm, height 535 mm, width 328 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this, I feel an odd mix of longing and resignation. It’s so orderly, so precise, but somehow also a bit melancholy. It reminds me of faded silk, all potential beauty tamed by age and... well, privilege. Editor: And privilege indeed! We're looking at "Gezicht op het kasteel van Meudon vanaf de tuinen," or "View of the Castle of Meudon from the Gardens." It's a drawing rendered between 1675 and 1717 using colored pencil and watercolor by Pierre Aveline. The scene is utterly aristocratic. The composition highlights human dominance over nature—nature shaped into submission to reinforce social hierarchies. Curator: Absolutely! You’ve got this imposing chateau perched perfectly at the center, presiding over manicured gardens. Each element screams control—nature molded into geometric perfection! I find it both visually compelling and deeply unsettling, it also looks so lifeless and untouched. I guess that's what an unachievable, artificial ideal ends up as. Editor: The style points squarely towards the Baroque, that age of spectacle and absolute power. Think Louis XIV, the Sun King, projecting absolute authority through architecture and landscape. Each meticulously placed bush or fountain reflects that centralised power. Every step or every breath of the privileged. And, as we know, who bears the burden of such a performance? Curator: The everyday folks. Always, right? Still, you can’t deny the technical skill. The rendering of depth, the almost photographic attention to detail…it’s breathtaking, even if what it represents leaves a bad taste in your mouth. Also, isn't this type of rendering for mass production? Does this suggest that the image had propaganda purposes? To disseminate ideas and ideals of French royalty to a larger crowd? Editor: Precisely. Prints like these often circulated widely, solidifying royal imagery in the popular imagination and functioning almost like social media of their day, spreading carefully curated narratives of wealth and legitimacy. Its political dimensions can be appreciated if we analyse its scale; think about the land needed to keep such display alive, think about what or who such amount of land displaced. Curator: Exactly, it's propaganda hiding under the guise of prettiness. Well, now I’m even more conflicted. The beauty seduces you even as the ideology repels you. Thanks for sharpening my view—I'm seeing much more now. Editor: Anytime. And maybe recognizing that tension—the push and pull between aesthetics and ideology—is the point. The drawing forces us to confront not just its own historical context but our own relationship to power and privilege, and that's quite a gift, regardless its history or purpose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.