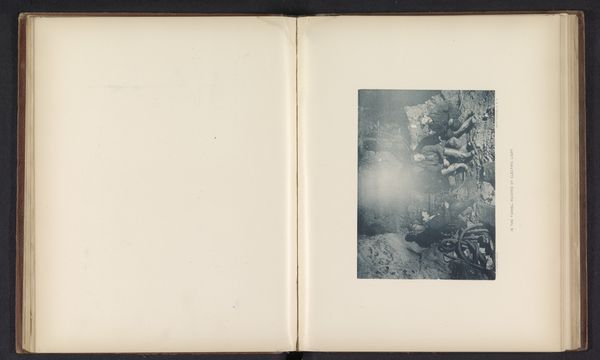

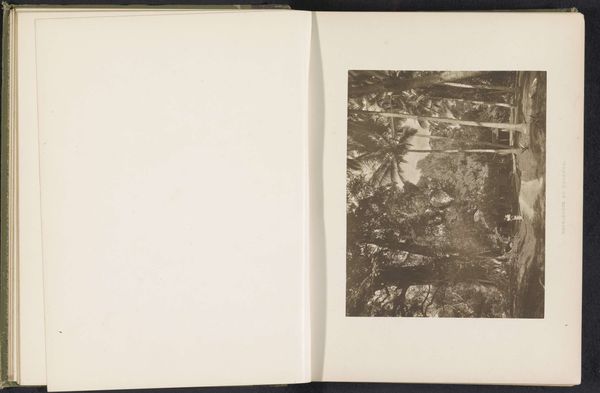

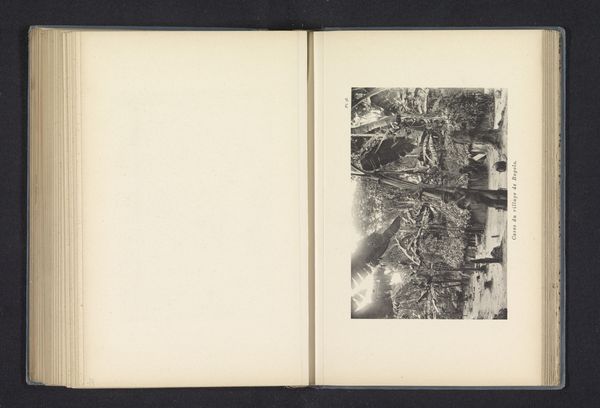

photography, albumen-print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 184 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an albumen print from 1896 by Henry William Cave titled "Rock Temple at Dambulla." Editor: It has an ethereal quality to it. Almost dreamlike in its muted tones and how the rock face emerges from the dark shadows. Curator: Indeed. Cave's work provides invaluable visual documentation of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, under British rule. This photograph speaks volumes about the colonial gaze and how sacred spaces were framed for Western consumption. Editor: The focus on materiality here is interesting. The use of the albumen print process, layering egg white and silver salts onto paper, to render a sacred rock temple raises questions about accessibility. This medium requires specialized labor to manufacture the photographic paper; it represents a specific mode of photographic production with its own network of circulation. Curator: Precisely. These images weren't simply objective records. They were actively constructed representations circulating within a very specific social and economic framework, shaping perceptions and perpetuating power dynamics. Consider, the scale—intimate album size—making this grand temple a manageable, possessable commodity for tourists and colonials alike. Editor: And look at the figures at the base of the temple; are they devotees or placed by the photographer to give us a sense of scale? There is a clear performative act being enacted here; one wonders whether the setting, though seemingly organic, is highly staged to serve the European pictorial tradition. The image subtly turns the Dambulla cave temple into a picturesque backdrop, not only downplaying its profound religious and cultural value but erasing it altogether. Curator: I concur. We must remain keenly aware of the photographer’s intention to shape our understanding, perpetuating historical and aesthetic narratives about both Ceylon and its monuments. These early photographic documents are more revealing than we often appreciate, underscoring the complexities of visual representation in colonial settings. Editor: It really invites us to reconsider how we look at landscapes captured by early photography—paying close attention to its labor, material composition, and the networks of making and viewing in those bygone eras.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.