tempera, painting, fresco

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

landscape

#

painted

#

fresco

#

oil painting

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

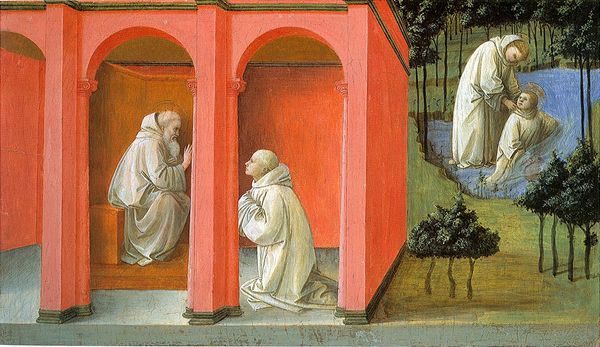

Dimensions: 40 x 235 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: As we move on, take a moment to observe "St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio" by Filippo Lippi, created around 1438. It’s a tempera on panel, currently residing in the Uffizi Gallery. Editor: The subdued color palette lends this piece a kind of humble gravity. I am interested by the lack of expressive features—there seems to be a communal suffering here, a sense of labor. Curator: Indeed. Let’s consider the production context. Lippi, trained in the Carmelite order, painted this during a time of significant civic projects in Florence, often funded by wealthy families to consolidate power. The material wealth, used to create narrative scenes, could then serve to legitimize social hierarchies. Editor: That is an interesting point! The placement of the ecclesiastical elite vis-a-vis other religious servants reveals a stratified society, no doubt. This painting highlights the church's active role in urban planning. Is it a form of soft power at work here, cloaked in religious guise? Curator: Exactly. The very tempera Lippi used involves pigment sourced from minerals and plants, carefully mixed and applied—a craft deeply intertwined with both manual labor and economic investment. The application itself showcases skill, but also a reliance on materials secured through a network of commerce and extraction. The value is constructed at multiple levels, would you not agree? Editor: Of course. It's worth analyzing Lippi's presentation of St. Fredianus' act itself: directing a river. Control of natural resources represents real political capital. To see him pictured with servants naturalizes it further; almost to the point of divine right. I see echoes of broader socio-political projects aimed at controlling populations through access. Curator: Ultimately, thinking about paintings like this involves confronting what the availability of pigments and a patron’s wealth meant for both the subject depicted and its reception. What’s made visible—and invisible. Editor: In summary, Lippi presents Fredianus as both a figure of religious reverence and an agent of ecological alteration; but more urgently, he highlights the complex power dynamics within Renaissance Florence, and how those were materialized—literally, onto panels like this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.