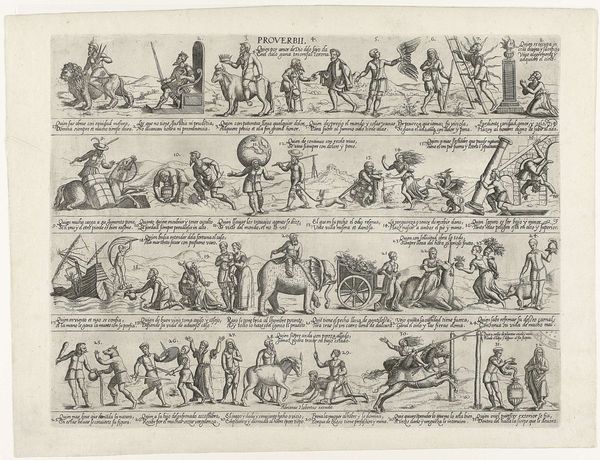

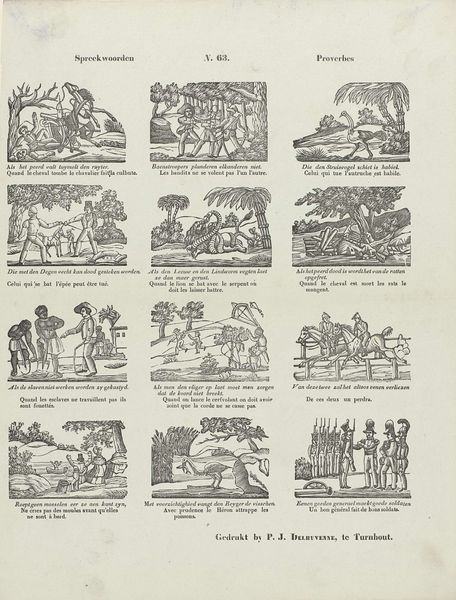

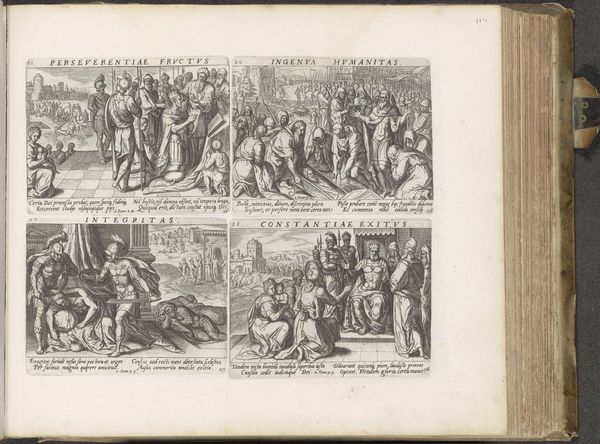

![Veldslagen, waar dat Mars zyn felle woed' kwam koelen, / En menig grooten held, den schicht ter dood deed' voelen [(...)] by Philippus Jacobus Brepols](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2QwMWVmNWEzLTg5MDktNDU5Ny05OGE5LWVkZjU0ZDFiZjFiYy9kMDFlZjVhMy04OTA5LTQ1OTctOThhOS1lZGY1NGQxYmYxYmNfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

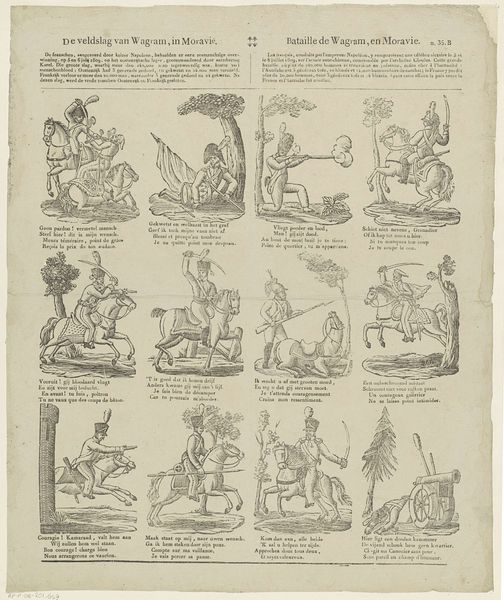

Veldslagen, waar dat Mars zyn felle woed' kwam koelen, / En menig grooten held, den schicht ter dood deed' voelen [(...)] 1800 - 1833

0:00

0:00

philippusjacobusbrepols

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

graphic-art

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 340 mm, width 391 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

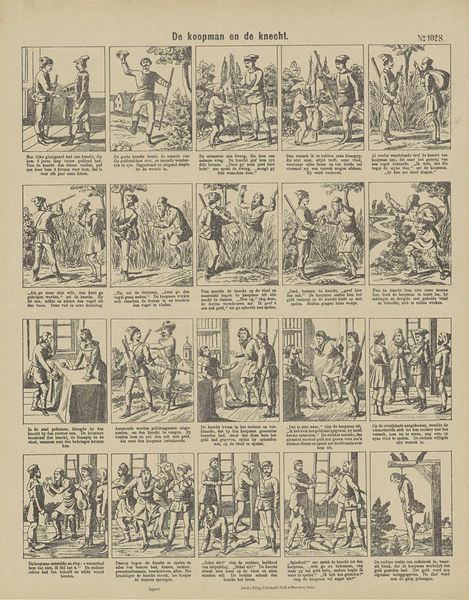

Editor: So, this print is titled "Veldslagen, waar dat Mars zyn felle woed' kwam koelen," created between 1800 and 1833 by Philippus Jacobus Brepols. It's currently at the Rijksmuseum, and it looks like an engraving, with lots of small scenes depicting battles and military life. It feels quite…didactic, almost like a history lesson in visual form. What's your take on this piece? Curator: I see it as a fascinating, albeit romanticized, construction of national identity during a tumultuous period. Consider the social and political landscape: the Netherlands had just gone through a revolution, and these types of prints were often used to instill a sense of patriotism and shared history. What stories do you think it’s trying to tell and for whom? Editor: Well, the scenes are quite heroic, even when they seem gruesome. It is clearly presenting war as something glorious, so I would suggest it might be for young, impressionable men. Almost propaganda in some sense. Curator: Exactly. And it connects to a long history of art being used to justify war, but consider *how* it does so. There's a distinct emphasis on leadership, sacrifice, and, notably, idealized masculinity. Does this "masculine" presentation reinforce existing social hierarchies? Editor: I think it does. These images, while seemingly about national pride, also subtly reinforce who belongs in the nation and who gets to define its narrative. They’re certainly not showing women involved in combat or leadership roles, just as support. Curator: Precisely. And think about the lines: this academic and realism style, in which the characters become symbols and generalized versions of manhood. The lines contribute to an idea instead of being concerned for reality. What do you make of that decision? Editor: That makes a lot of sense; the romanticized depiction and the generalized lines do help create the symbolic, rather than historical depiction of nation and citizen. I didn't realize how deeply gender and class were embedded in even seemingly straightforward historical depictions. Curator: Right. It reminds us that art is never neutral, and historical depictions can act as both records of the past and prescriptions for the future. I never considered the importance and presence of constructed masculine figures in forming this art piece.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.