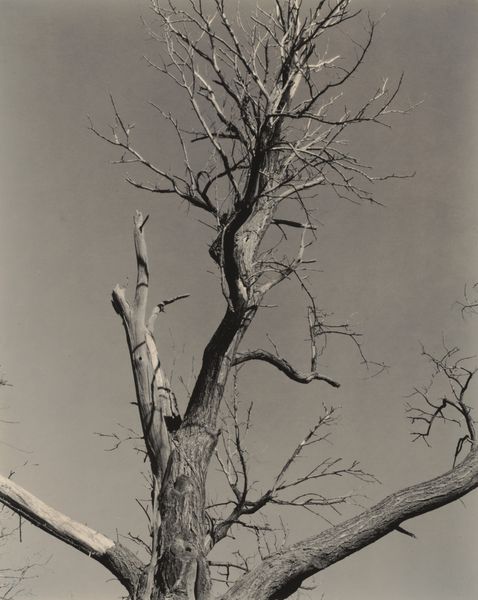

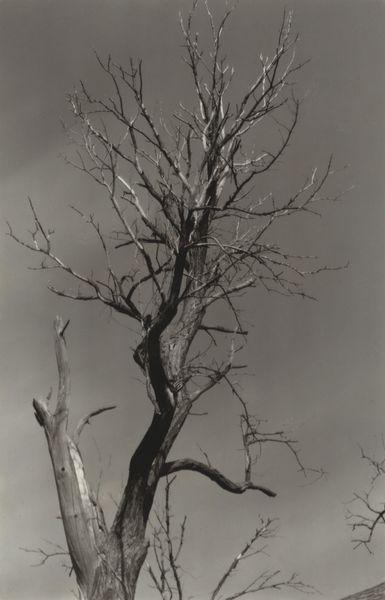

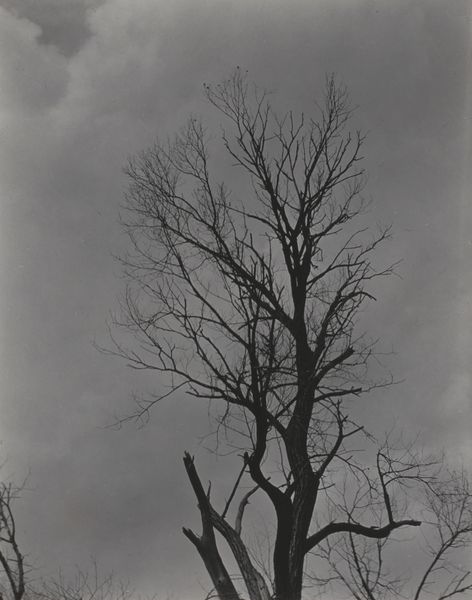

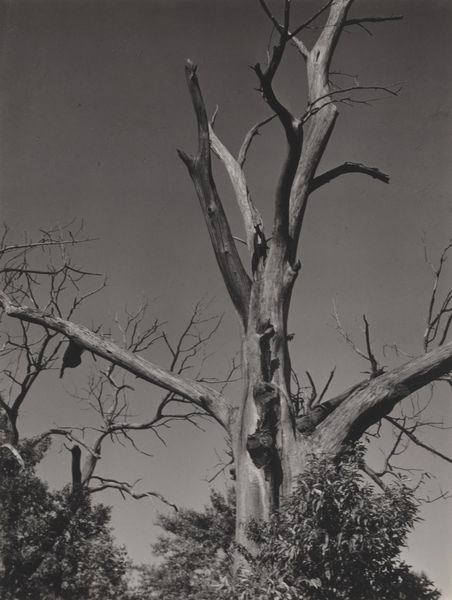

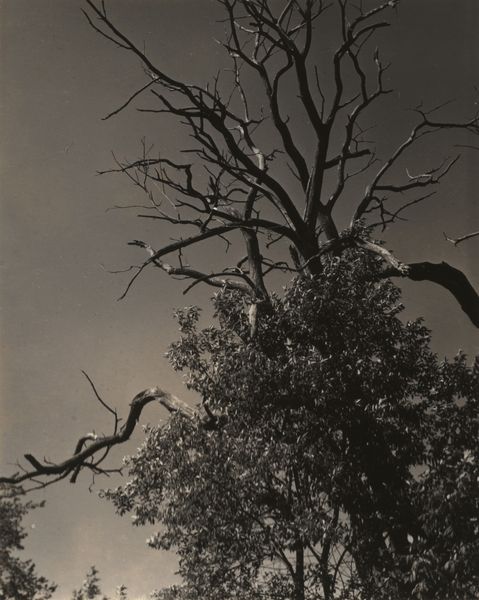

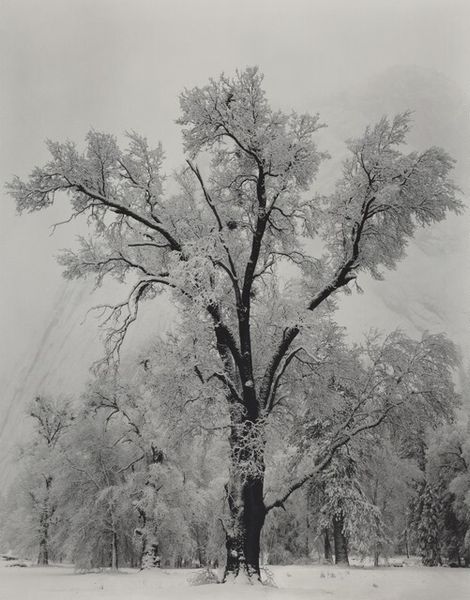

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 24.2 x 19.3 cm (9 1/2 x 7 5/8 in.) mount: 56.5 x 46.4 cm (22 1/4 x 18 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

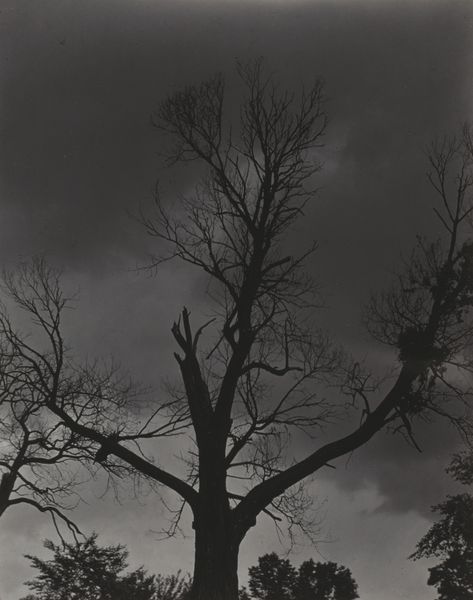

Curator: I'm immediately struck by how imposing this image is, a monumentality captured in stark monochrome. It feels intensely personal, a kind of raw confrontation with mortality, perhaps? Editor: Absolutely. What we’re looking at is a gelatin-silver print by Alfred Stieglitz, titled "The Dying Chestnut Tree," from 1927. A very loaded image, even the title tells you where we are headed. Trees often become cultural symbols for strength and longevity. What do we do with a dying one? Curator: A gut punch, frankly. It’s like witnessing a slow, agonizing decay. But there’s a stark beauty in it too, wouldn’t you say? Look at the skeletal branches reaching up, almost clawing at the sky. Is this what we leave behind? Are we clinging onto something unattainable, forever reaching into the beyond, while falling apart at the core? It is haunting, and kind of beautiful in an awful sort of way. Editor: Well, Stieglitz was deeply invested in finding equivalents – objective correlatives, if you will – for internal emotional states through photography. A dying tree can represent all sorts of concepts related to life's inevitable end: aging, resilience, loss of potential, and, as you suggested, grappling with something larger than oneself. A romantic vision, filtered through a very modern lens. The tree’s silhouette reminds us that nature is temporary and finite. Even the strongest natural forms fail over time, as with life. It all fades, which reminds us to appreciate what is and let go of what was. Curator: But that harshness also speaks to the brutal realism that underscores Stieglitz's modernism, doesn’t it? Stripped bare of any sentimental foliage, it stands defiant, a twisted monument to endurance. The light etching away the bark almost feels like pain. You could get lost in that stark contrast, just feeling the image like you’re reading Braille with your soul. Editor: The stark monochrome definitely amplifies that feeling of raw vulnerability, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths. You can see the echoes of romanticism in that search for sublime feeling in nature, a concept we know dominated painting a century prior, but Stieglitz takes it and distills it into something far more immediate and personal. So powerful is its impact. Curator: So, next time you are feeling lost and helpless, maybe this artwork will help you come to peace with those very valid emotions, or find catharsis. That’s the great thing about art – the viewer, when connecting, finds its message personally. It becomes less about the artist and more about our relationship to his creative spark. Editor: Precisely. Stieglitz offered a mirror, perhaps, more than a window, reflecting the eternal cycle of creation, destruction, and rebirth – a testament to our own human frailty.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.