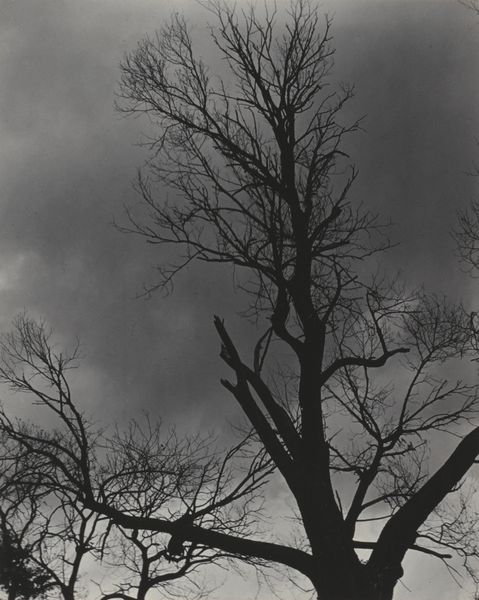

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

#

realism

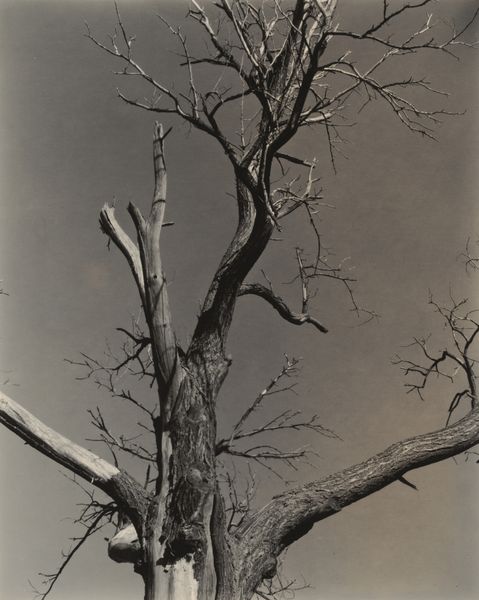

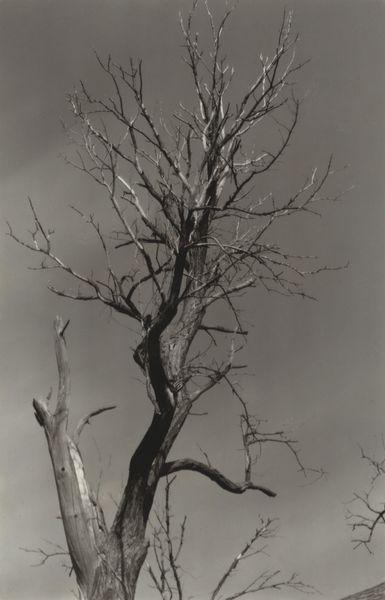

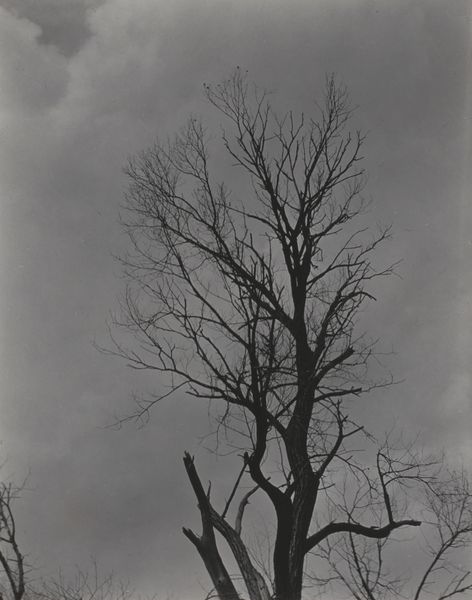

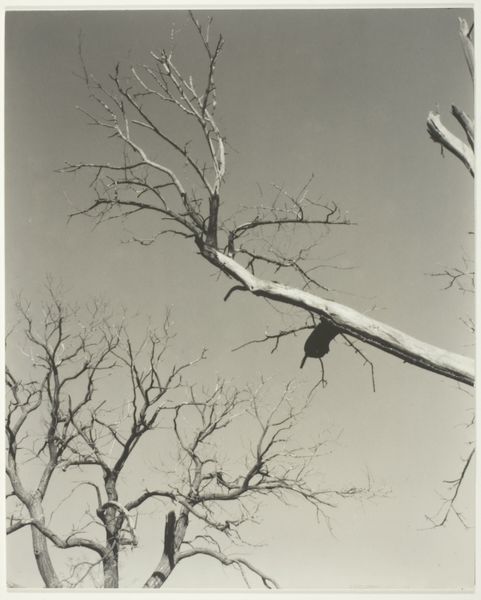

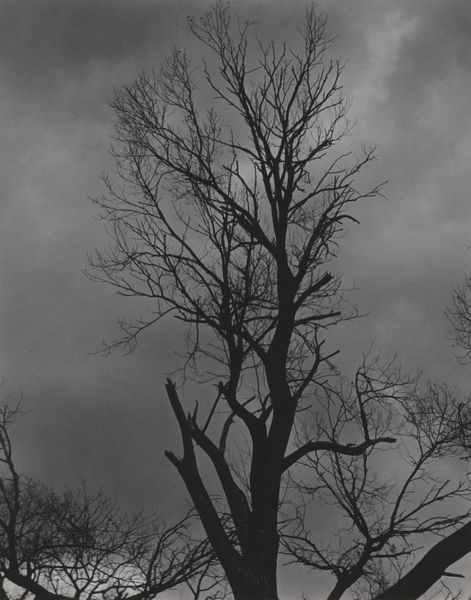

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 24.1 × 19.2 cm (9 1/2 × 7 9/16 in.) mount: 56.5 × 46.35 cm (22 1/4 × 18 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

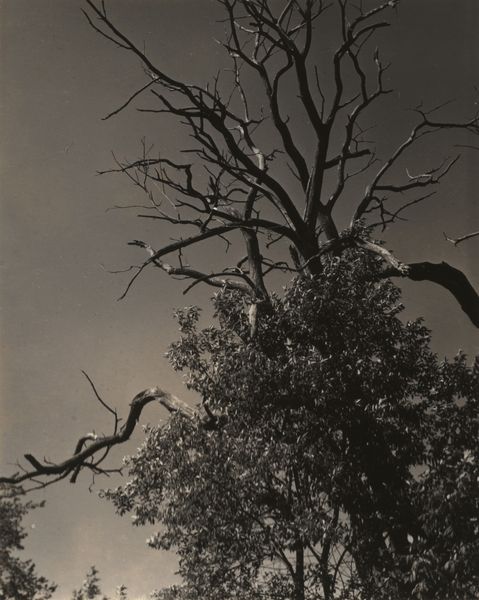

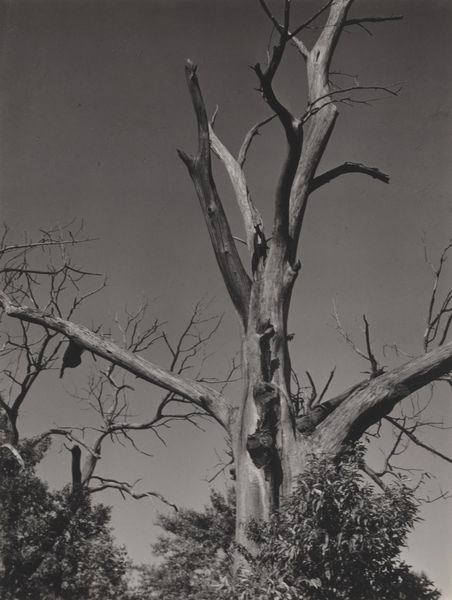

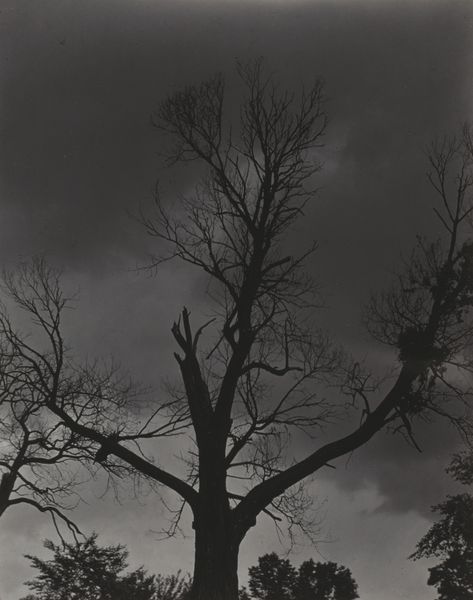

Curator: Looking up at the frame-filling branches in Stieglitz's gelatin silver print, "The Dying Chestnut Tree," made in 1927, is a rather melancholic experience. Editor: Melancholic is spot on. There's something incredibly stark and raw about the bare branches reaching up against that seemingly endless sky. The materiality, the grain of the gelatin silver process, it all contributes to a sense of vulnerability and decay. It makes me think of labor, really, how demanding is nature to accept the process of decaying with dignity? Curator: Stieglitz had a way of elevating everyday subjects. Think about his cloud studies. This tree, in its final stage, becomes a portrait, doesn't it? Pictorialism’s last breath transformed into modernism’s straightforward observation of what is. What do you make of his move away from soft focus? Editor: Well, by focusing so sharply on the details - the rough bark, the broken limbs - he seems to strip away any romantic idealization of nature, yet is that possible?. It feels so aligned with the Machine Age, everything stripped down to its essential structure, to pure process. It challenges what we consider artistic labor: he did not "create" the image per se. He used tools to reveal a new aesthetic within something dying already. Curator: Right, he’s framing a subject that resonates deeply with the anxieties of the time. Remember, the 1920s were marked by the trauma of World War I, shifting social values. Is it possible that the dying tree reflects the end of an era or old values in a new capitalistic era? Editor: Precisely! And isn't there a social dimension here too? A commentary on obsolescence. Just as industries evolve and displace workers, nature, even in its majestic form, is subject to decline and eventual decay as the world turns increasingly "urbanized". Curator: It really asks questions about time, doesn't it? And our own place within these cycles of creation and destruction. Editor: Exactly. The starkness almost commands the viewer to re-examine the aesthetics of deterioration as they become active consumers in this new landscape. It really asks questions about nature, obsolescence, time, capitalism...all intertwined. Curator: An unsettling beauty. I'll remember this. Editor: It urges you to be conscious of how our very own act of beholding something decaying marks it as consumption within culture, really impactful piece.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.