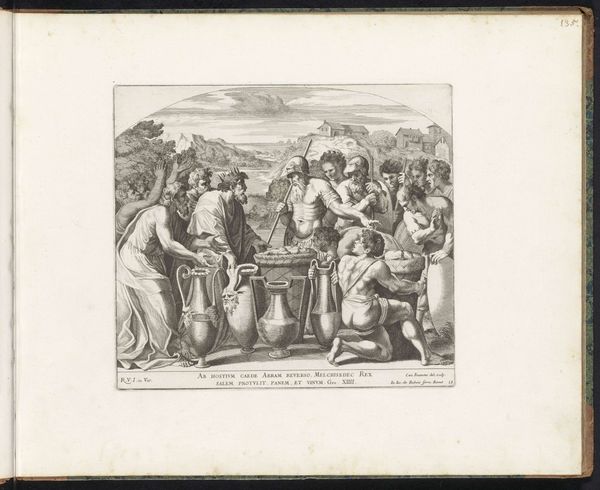

print, engraving

#

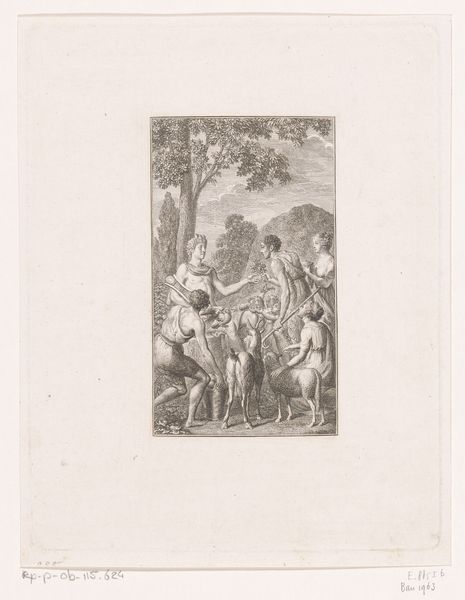

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

dog

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 157 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, look at this Baroque print. It's called "Allegorical figures with coats of arms at a fountain", made somewhere between 1680 and 1702 by Joseph Mulder. Currently it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a strange little drama unfolding, isn't there? Everyone posed so formally, with a cheeky dog paddling away. I’m initially struck by the tension between the almost dreamlike atmosphere and the precise linework typical of engravings. Curator: Absolutely. It seems on the surface very fanciful but if you zoom in the allegorical figures each have significance, they speak to historical power and dynastic lineage. See, each of them is supporting the Guntherstein family’s coats of arms. There’s an almost unsettling insistence on preserving lineage in what is, essentially, a fleeting artistic medium like print. Editor: Print as propaganda! It is a potent combo when aimed at solidifying social hierarchy, I find myself thinking about Mulder's engraving process, especially the choice to showcase heraldry through such labor-intensive, yet repeatable means. It makes the question of artistic labor as class labour jump right into mind. Were such elaborate designs typically outsourced or crafted in-house for wealthy families like the Gunthersteins? Curator: I think both things are true, he likely had studio assistants but would oversee every little line. Mulder was at the time, if not famous, then certainly an accomplished and sought-after artist. So to be employing that talent for what ultimately functions as glorified advertising is quite the thing. Don't you think there is something almost mournful about how seriously everyone takes it? The woman seated has this wonderfully theatrical posture. She's doing *her job*. Editor: It is like an ad. A status announcement rendered in copper and ink. Though the figures appear grand, let’s not forget how these images enter the domestic spaces. Who encountered it? Did those interactions change or maintain social roles? I wonder, with all this rich detail, what statement it tried to make. Was it really effective as branding or just elaborate decoration that fed into capitalist appetites and then… disappeared from collective memory. Curator: Maybe its effectiveness is precisely how normal the conceit feels to us, you know? That this over-the-topness, it fades away and feels unremarkable in retrospect. To ask "did it work?" is to fail to reckon with the pervasive ways something like power is reproduced—literally, here. It gives us an occasion to rethink our relation to printed matter and luxury itself. Editor: Indeed! Considering the artist's process and these characters situated at the intersection of production and visual delight, gives a deeper look at how the work blurs and reveals, questioning those values it so deliberately meant to uphold.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.