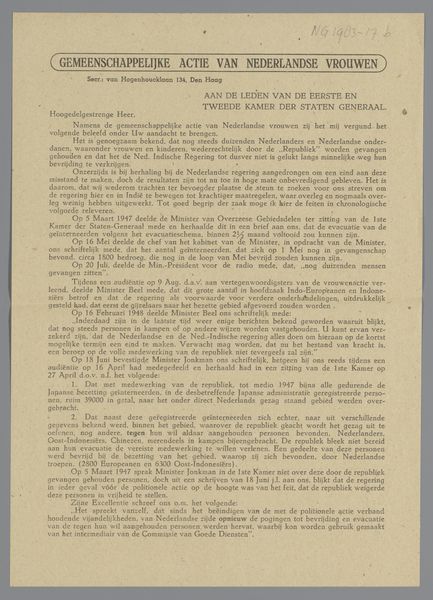

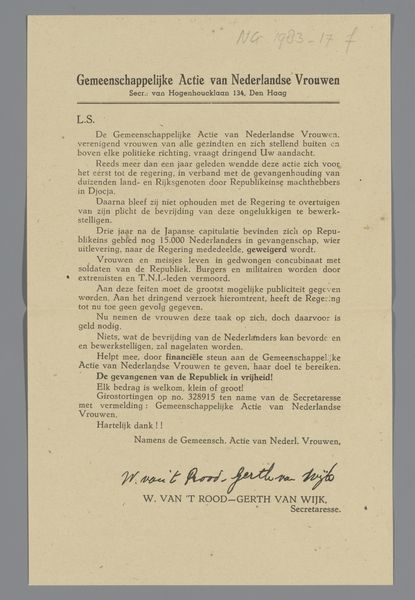

Nog steeds 15000 Nederlanders de gevangenen van de Republiek Djocja 1948

0:00

0:00

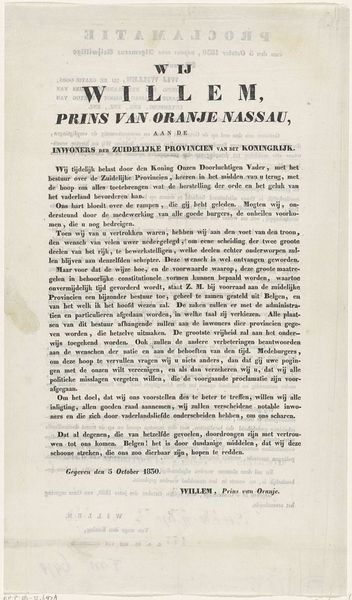

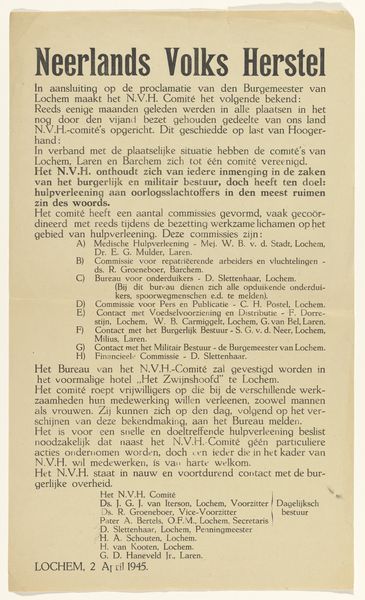

print, paper, typography, poster

#

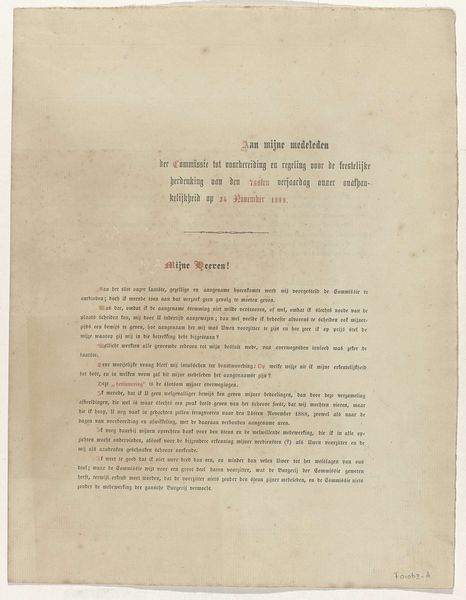

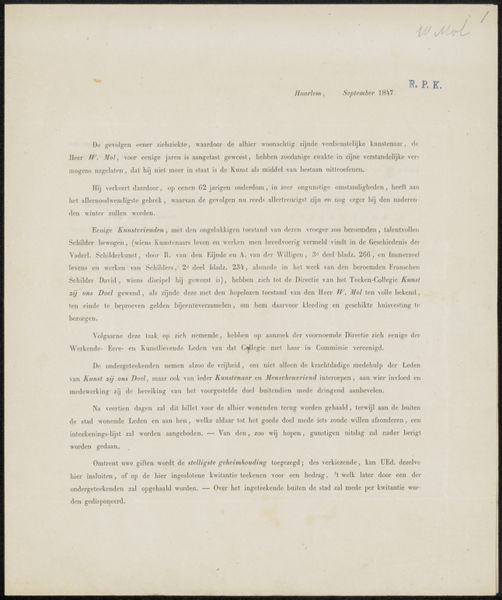

newspaper

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

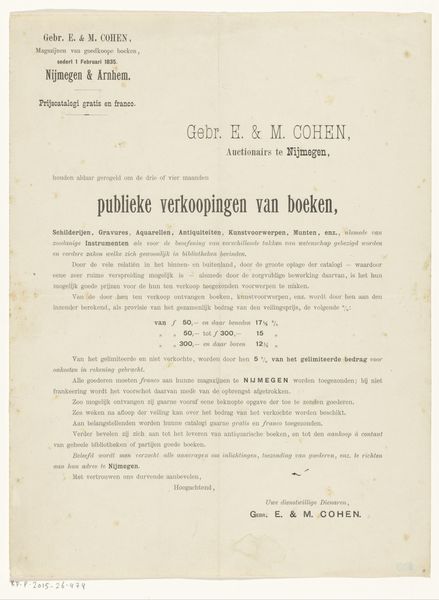

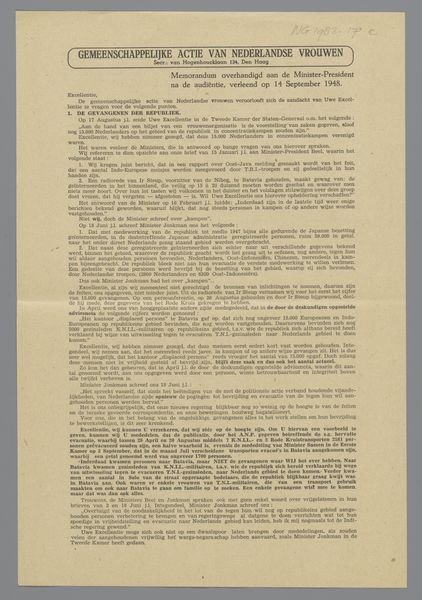

design document

#

paper

#

typography

#

stylized text

#

history-painting

#

poster

Dimensions: length 31.8 cm, width 22 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Artist: Here we have "Nog steeds 15000 Nederlanders de gevangenen van de Republiek Djocja," which roughly translates to "Still 15000 Dutch People Prisoners of the Republic of Djocja." It's a print, likely a poster, made in 1948 by W. van 't Rood-Gerth van Wijk. It has this sort of Dutch Golden Age typography, but for a very different purpose. Curator: My immediate reaction? Stark. Bleak. It looks mass-produced on cheap paper, probably cranked out in large quantities. This isn’t some gilded-age masterpiece; it's ephemera meant to be consumed and discarded. The weight of those numbers – 15,000 – coupled with the typography suggests the urgent distribution of a painful, difficult message. Artist: Absolutely. The weight of that number does so much work. There’s a rawness here, the plea jumping off the paper. I feel the desperation of those trying to raise awareness and rouse action, imagining them collating and distributing these from a cramped office. Curator: Precisely. Let’s think about what paper and printing represented in post-war 1948. Rationed resources, the mechanics of propaganda, grassroots movements vying for public attention through accessible means of communication. This isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s about the tangible realities of a nation grappling with conflict, struggling for resolution through the channels available. It seems aimed directly for social participation by ordinary citizens as it asks its reader to share their opinions at the end, and solicit signatures for it, implying the collective value of such responses. Artist: I see this piece not just as an artifact of war, but a human cry. Van ‘t Rood-Gerth van Wijk manages to convey deep worry about the captured, even when it’s rendered with mass media. If we see beyond the paper and the ink, we realize a desperate soul pleading for fellow human beings who had become invisible behind a conflict, still worth fighting for. Curator: And by acknowledging that cry, we’re not only reflecting on historical injustice, we are actively analyzing its presentation within social space. It is more than text printed on paper. The materiality allows this injustice to be made known through affordable dissemination. That, to me, makes the whole picture speak.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.