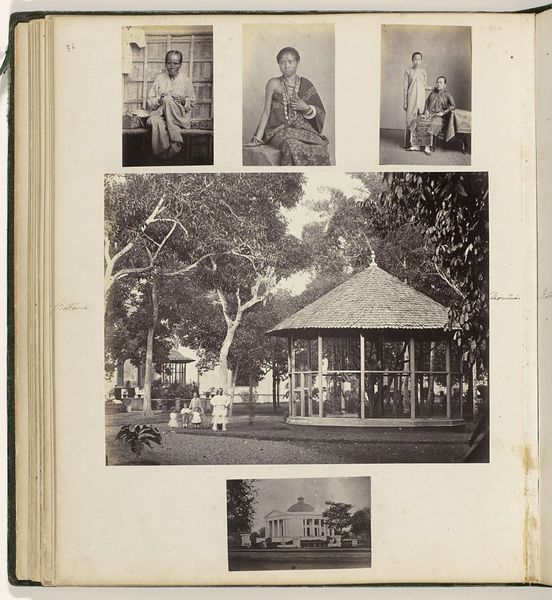

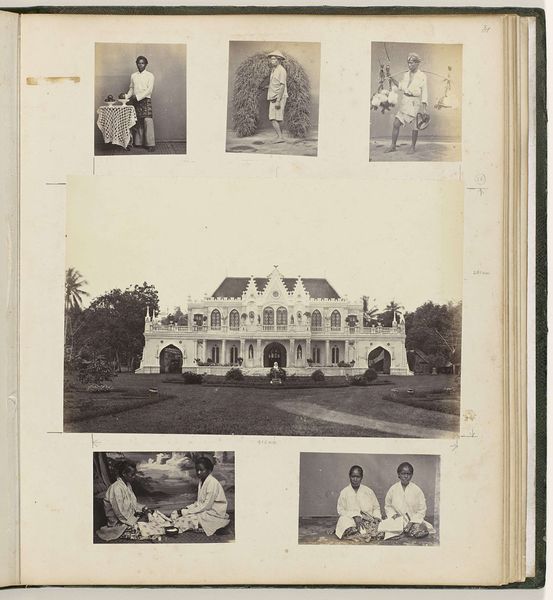

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

asian-art

#

indigenism

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 305 mm, height 189 mm, width 242 mm, height 80 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

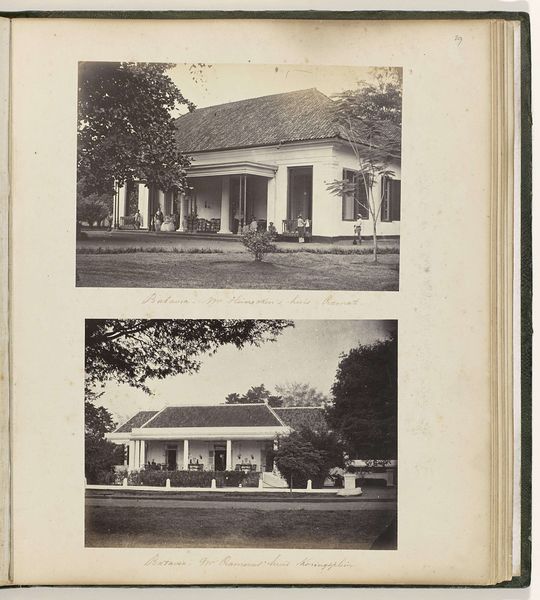

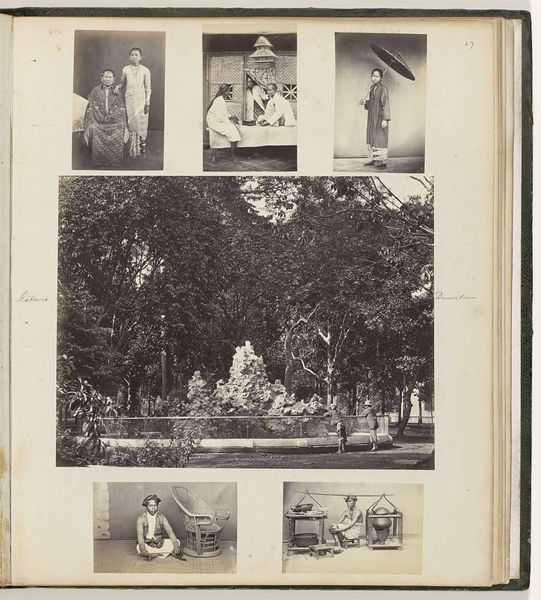

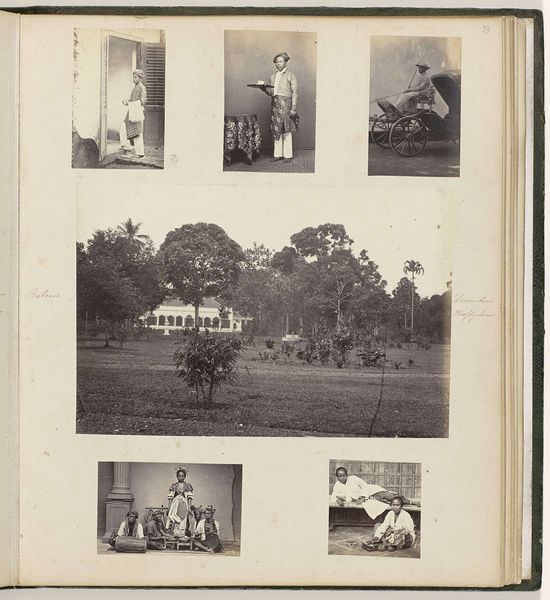

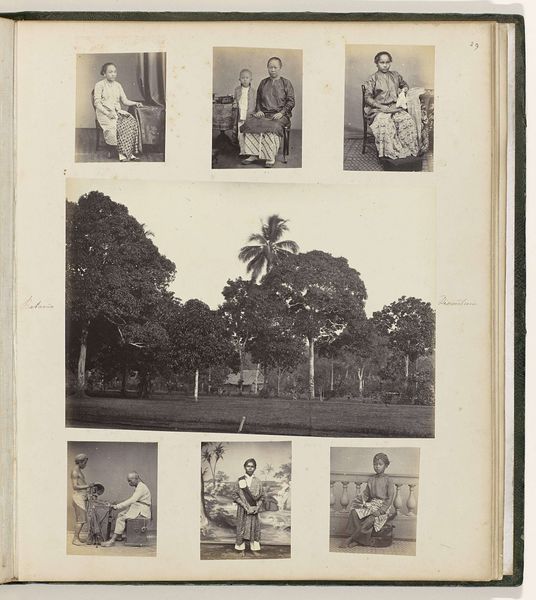

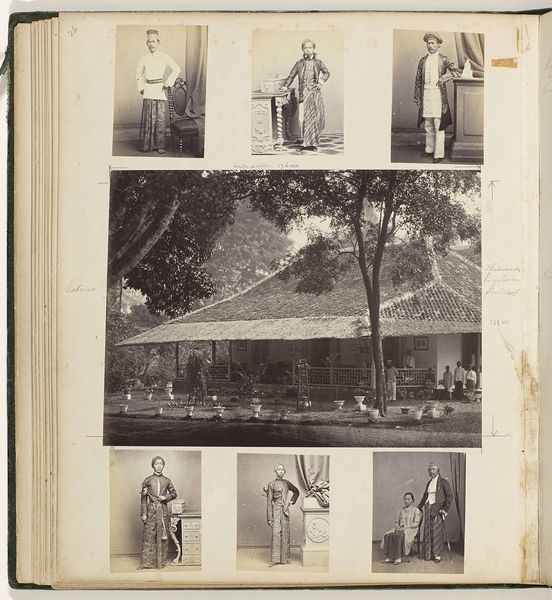

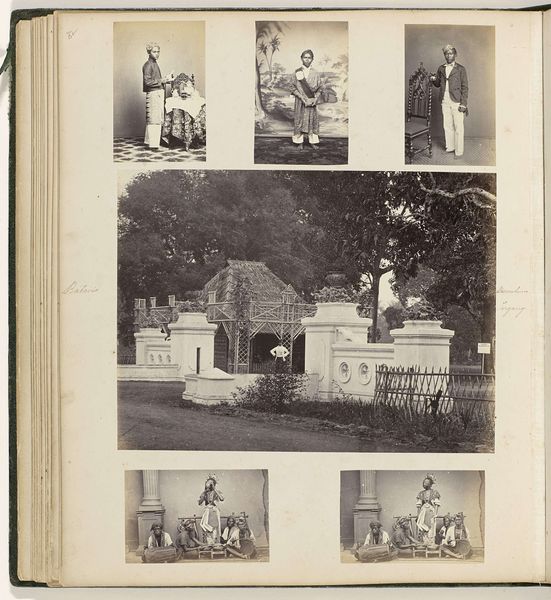

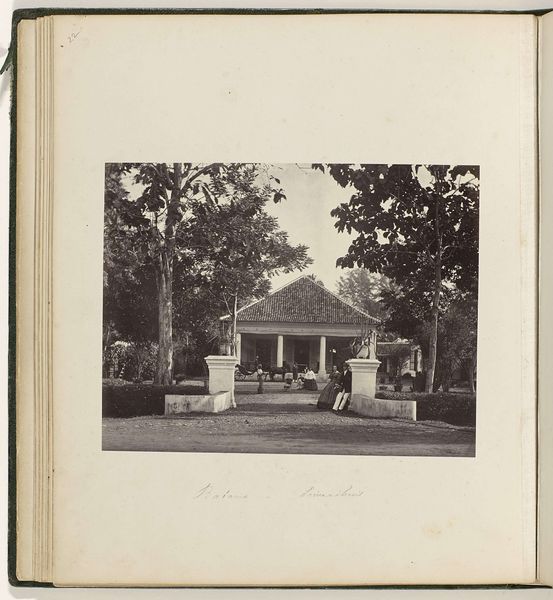

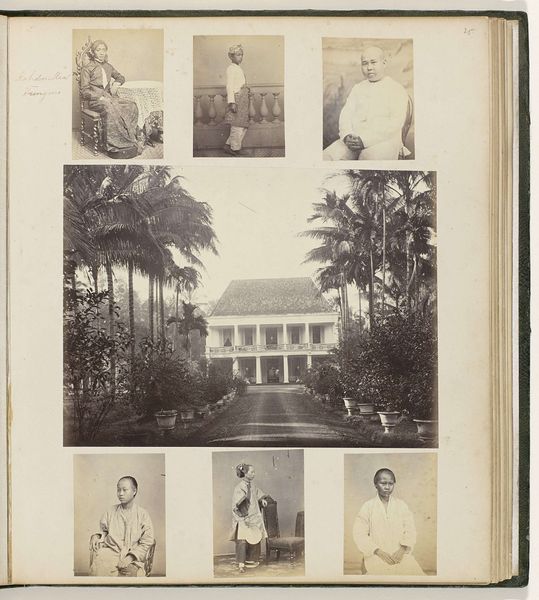

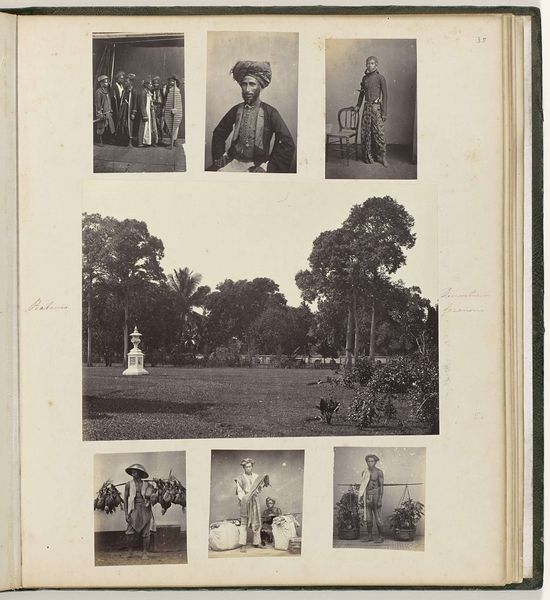

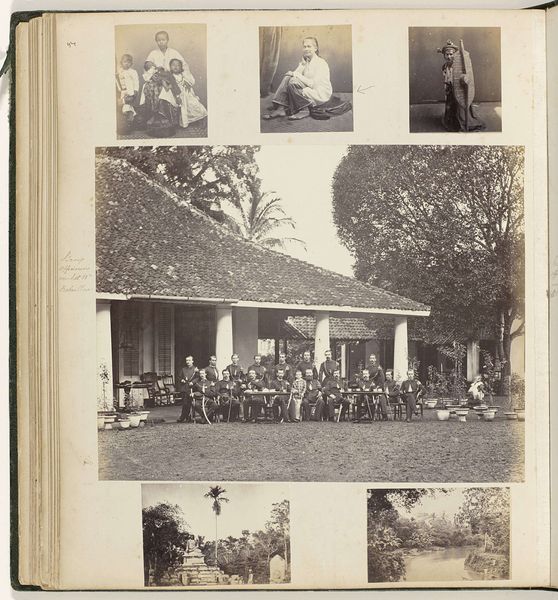

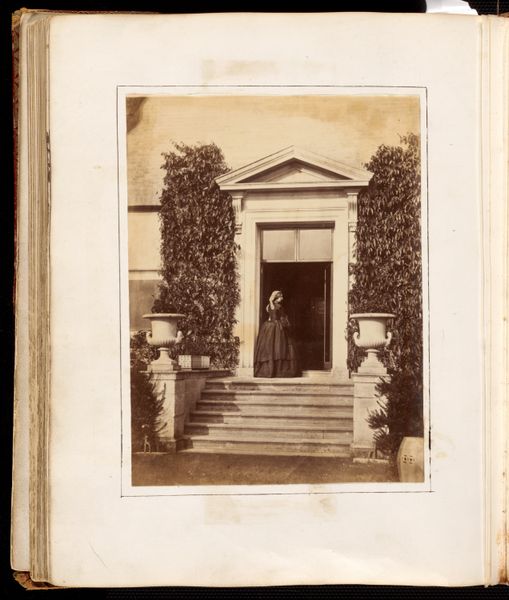

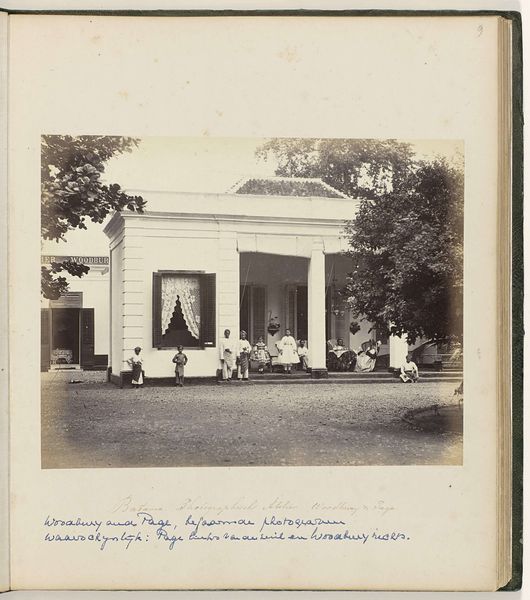

Curator: Take a look at "Church and Six Portraits," dating back to between 1863 and 1866, by Woodbury & Page. This albumen print gives us a glimpse into 19th-century Indonesia through a colonial lens. Editor: My first thought? Melancholy. The tones are subdued, almost sepia, lending it an air of nostalgia. It's a collage, of sorts, with individual portraits surrounding a neoclassical-looking building—a church, it seems. Curator: Precisely. What strikes me is the presentation itself—the calculated arrangement. It reflects the Orientalist fascination with cataloging and documenting the "exotic." The church represents the imposition of Western influence. Editor: Absolutely. I’m caught by the faces, though. Those portraits have stories behind them that we'll never know. I'm guessing they were posed, of course. There is a certain power dynamic suggested through the image layout here, I'd say. Curator: Indeed, the photographer would have dictated the setup for each of those images to convey specific narratives—likely reinforcing existing colonial power structures and projecting Western ideals onto Indonesian subjects. These photographs participated in constructing and disseminating particular versions of Indonesian identity. Editor: And there it is, the inevitable imposition, but I also see individual dignity resisting categorization—a spark of uniqueness in their eyes or bearing. Even through that photographic agenda there remains some kind of life I see. The portraits make you feel a connection, even though so distant from when and how they lived. What about the inclusion of a building then—is that intended to remind one of its history as a part of a wider city scape? Curator: Yes, precisely. It serves to emphasize and amplify colonial architecture of Batavia cityscapes during a time when architecture represented and communicated Western societal and governmental rule. Editor: In terms of my final thoughts, as an object it intrigues and stimulates reflection on how images frame our perceptions of other cultures. And of how little has changed regarding imposed expectations. Curator: Well articulated! The beauty of studying such an artefact from this era is that it allows us to critically examine these constructions and challenge the lasting impact of colonialism's visual legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.