albumen-print, photography, albumen-print

#

albumen-print

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

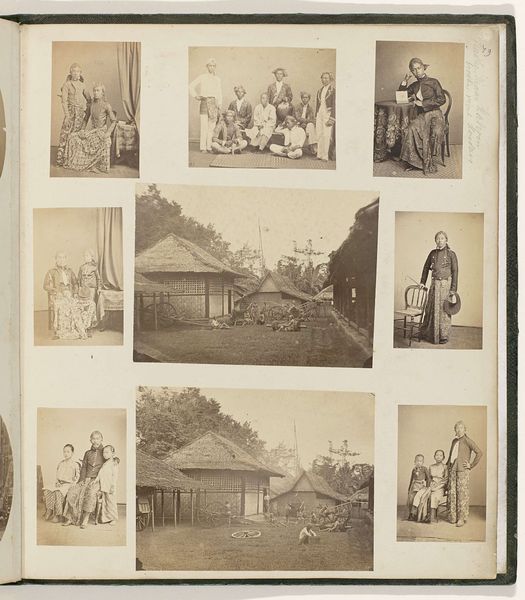

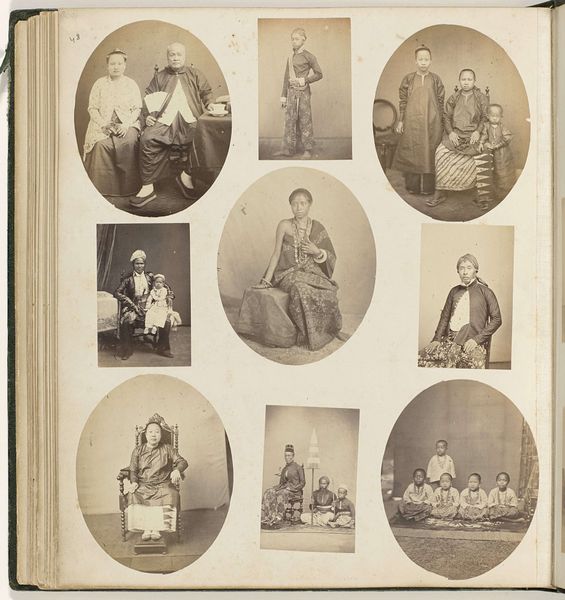

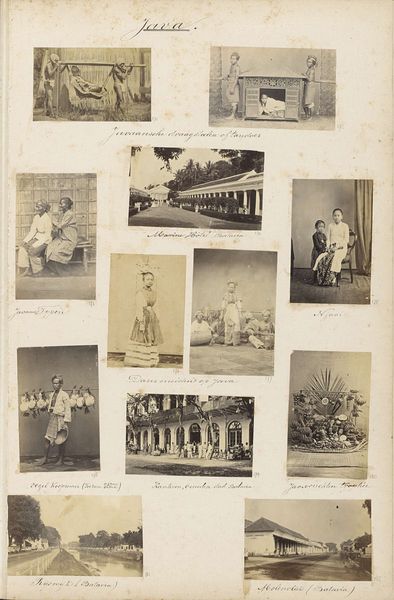

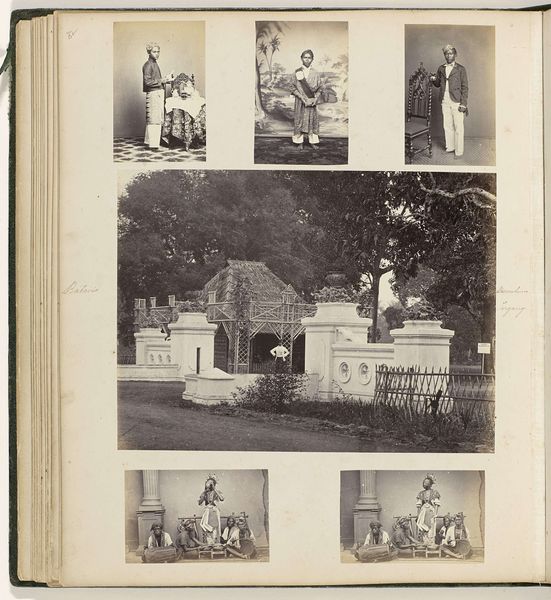

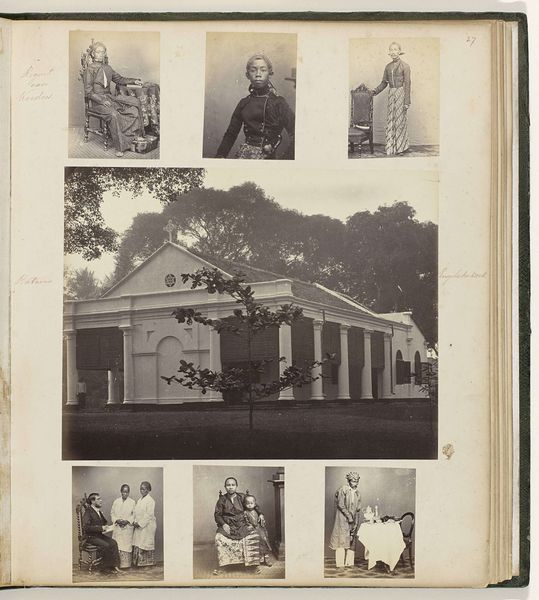

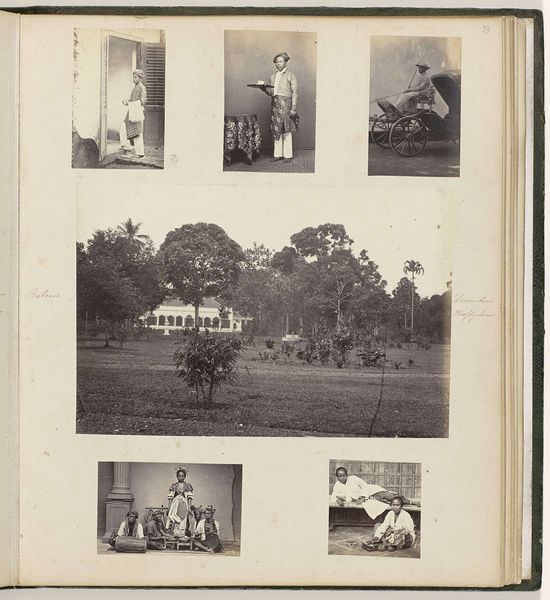

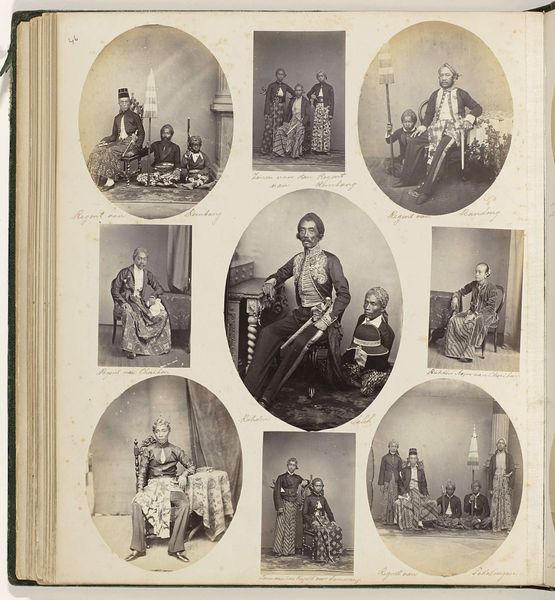

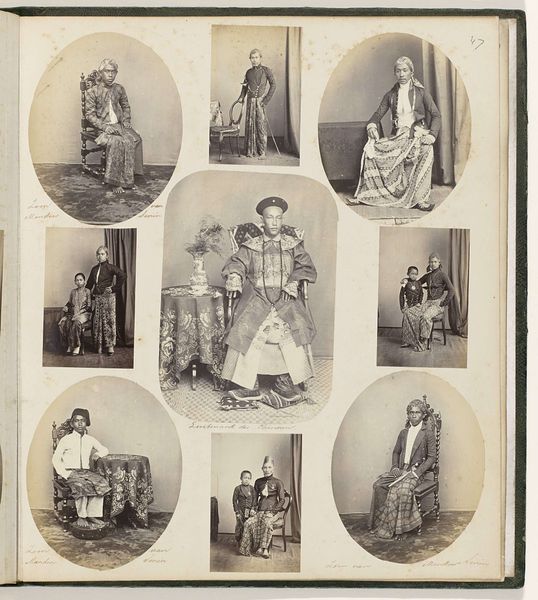

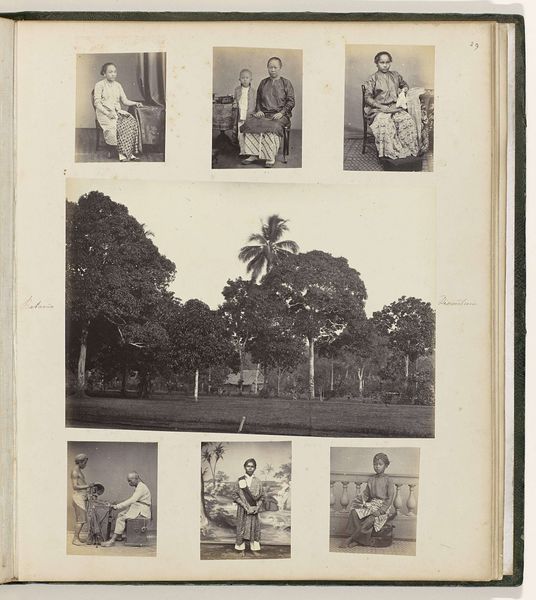

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 305 mm, height 177 mm, width 242 mm, height 80 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

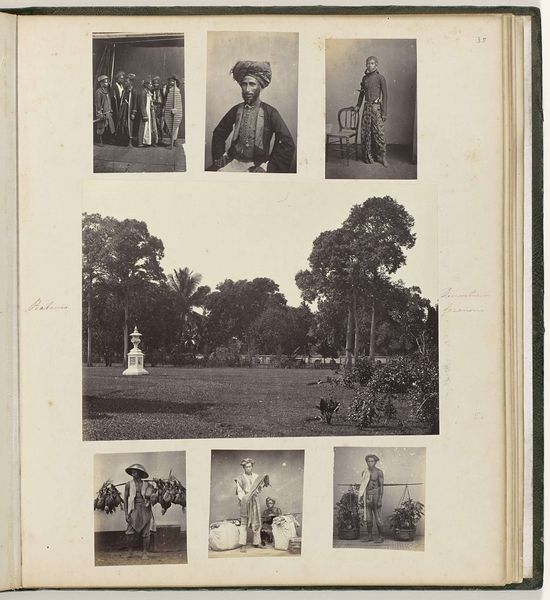

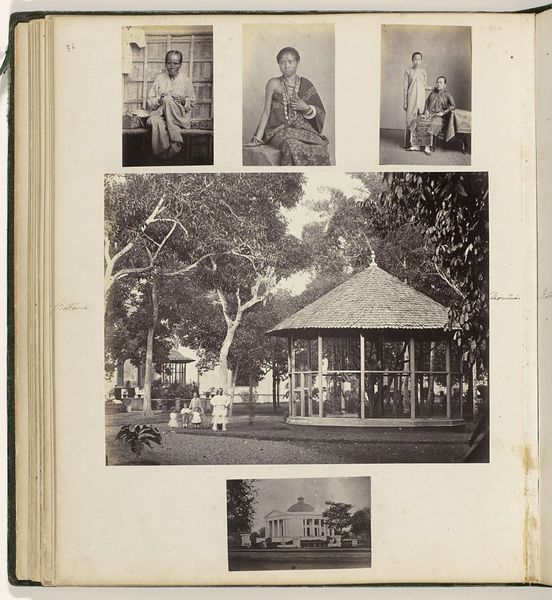

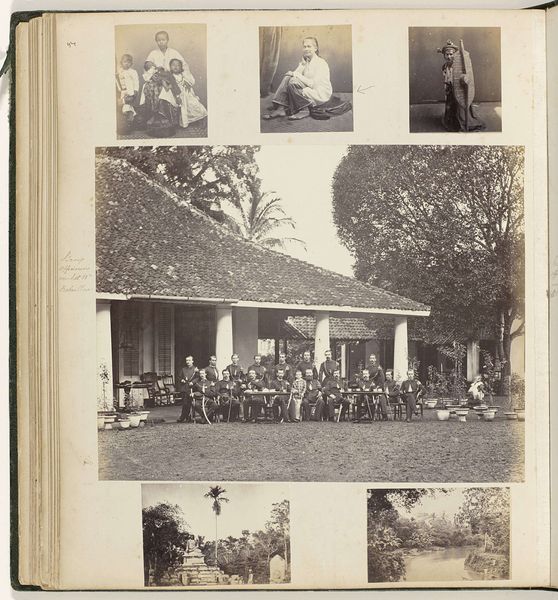

Curator: This is a fascinating albumen print from between 1863 and 1866 by Woodbury & Page, titled "Woonhuis en zes portretten"—a house and six portraits. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, the composition strikes me. It's not just a collection of images; the juxtaposition of the architectural photograph with the posed portraits creates a powerful, if perhaps unintentional, narrative about colonial representation. Curator: Indeed. Focusing on form, the image’s tonal range and careful arrangement immediately signal a meticulously constructed presentation. The house, centrally located, anchors the page, visually grounding the surrounding portraits. Editor: But it’s precisely that anchoring that raises questions. The portraits, presumably of Indonesian individuals, are relegated to the periphery, literally framed by the architecture. It evokes a dynamic that reduces people to mere exoticized artifacts within a colonial landscape. Curator: Certainly, we can observe the rigid formalism of portraiture during this era; the subjects, framed meticulously with props and furnishings, are less about capturing individual essence and more about constructing an image. Notice how the photographer captures each sitter and renders the architectural setting in great detail. Editor: Detail yes, but let’s think about that gaze. Consider that, while precise, it also reflects a constructed gaze—the photographers, a European company—capturing what they and their Western audience expect to see: a demonstration of control and power dynamics inherent to colonialism. The use of photography itself as a tool for documenting and thus claiming possession of the landscape and its inhabitants cannot be ignored. Curator: The play of light and shadow across the architecture is meticulously composed—we can interpret the house as a geometric study or an expression of structural values. Editor: True, and while admiring those aspects, we cannot ignore how this photograph also exemplifies the Orientalist aesthetics prevalent during the colonial period, shaping how we perceived the "Orient" through constructed imagery, thus othering communities to reinforce colonial power structures. It reminds us that visual aesthetics are never apolitical; here it's a quiet archive of colonial social engineering. Curator: Viewing the piece with both eyes opens a richer, complex understanding of the history embedded in these beautiful, though obviously constructed, vintage photographs. Editor: Precisely, making these layers visible encourages visitors to unpack not just what is on the surface, but to confront uncomfortable legacies still shaping how we see one another today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.