painting

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

baroque

#

painting

#

figuration

#

intimism

#

group-portraits

#

genre-painting

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

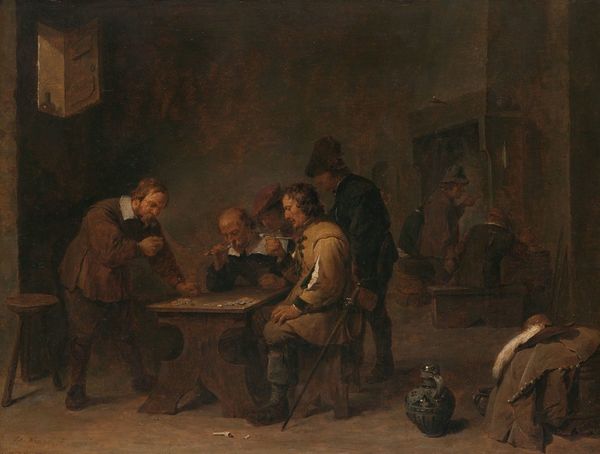

Curator: Immediately, I see camaraderie in the warmth of this dimly lit space. Is that raucous laughter hanging in the air? Editor: It certainly feels that way. We're looking at Adriaen van Ostade's "Three Peasants at an Inn", a painting showcasing a genre scene steeped in the intimism typical of his oeuvre. Curator: Ostade often returned to scenes of daily life. Here, we see three men, presumably peasants, gathered, drinking, playing music… a common, relatable scene. The man with the tankard held aloft seems the very picture of revelry, almost Dionysian. What’s striking is how these seemingly mundane moments carry such a profound emotional weight. Editor: It’s the way Ostade uses the symbolism of the tavern, isn’t it? Inns have historically been public spaces, outside of traditional social regulations. That's emphasized here; notice how one figure proudly brandishes a glass while the other strums away on an instrument. Both actions serve as archetypes for the tavern—a zone of mirth where one's expectations for good-mannered propriety are gladly reduced. Curator: Absolutely. These visual elements offer insights into the broader context of tavern culture in Dutch society at the time. A space of liberation, certainly, but perhaps also an escapist setting in a world of socioeconomic strain. The tavern itself could even function as a stage on which status lines became obscured. Editor: Precisely, the pipe laying on the floor in the lower right—is that one dropped in contented distraction or does it reveal the temporary abandonment of responsible routines? And the window: so small, it's as if the subjects want to emphasize their own enclosed atmosphere. Curator: Van Ostade painted many scenes of the downtrodden. Do you think such work helped to foster greater civic compassion towards impoverished communities? Editor: It’s possible, yes. At the very least, it invites us to reflect on the complexities of societal norms and human nature itself. To examine the everyday experiences of a social group commonly rendered invisible by historical discourse. Curator: Looking at it now, Ostade created more than just a glimpse into a tavern. He distilled the human desire for connection and reprieve into one frame. It strikes me, our modern pursuit of community isn’t all that different, is it? Editor: I agree completely. It’s a compelling testament to the power of imagery and storytelling that continues to resonate centuries later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.