Dimensions: height 144 mm, width 269 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

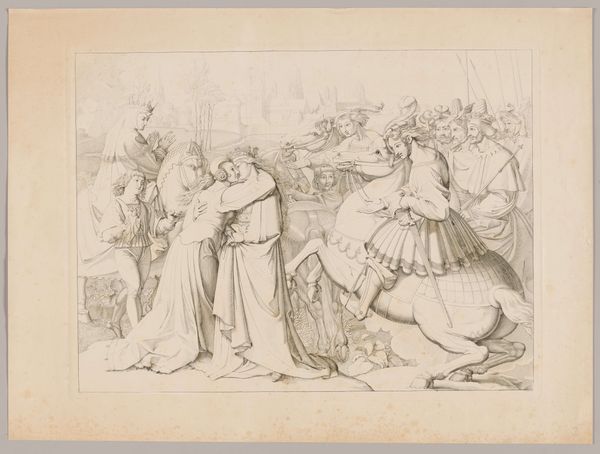

Curator: Here we have "Dancing Couples with a Duo of String Players" by Willem Linnig the Younger, likely created between 1852 and 1890. The medium is pen and ink on paper. Editor: It has this immediate energy. It feels fleeting, like a snapshot of a lively gathering caught on paper. The scratchy linework makes it raw. Curator: Absolutely, the rapid strokes suggest movement and spontaneity. Linnig comes from a family deeply entrenched in the artistic fabric of 19th-century Antwerp. Looking closely at the process, the hatching, you can see the hand of the artist so directly. What sort of labor goes into evoking leisure like this? Editor: It certainly reflects a particular societal bubble of the time. These gatherings were spaces for socializing, negotiating social status, but also often spaces of constraint and the performance of rigid gender roles. The dancers and musicians aren't simply expressing joy; they are performing a ritual loaded with cultural meaning and limitations. What social stories are hidden within the dance itself, within those very gestures? Curator: Well, the material execution reveals Linnig's mastery and understanding of the marketplace for art at that time, and reveals something about the access he might have had to education and materials. He clearly caters to the tastes of a particular consumer group within this historical period, a middle class with growing wealth and the leisure to enjoy these scenes. Editor: Exactly. He portrays a kind of fabricated intimacy. The romantic era's obsession with emotion hides power dynamics, you see. But the act of capturing it becomes interesting itself when considering the hierarchies it naturally reifies. It asks the viewer who and how we celebrate. And what about those he doesn't celebrate. Curator: He's choosing to document a moment steeped in a certain aesthetic and cultural privilege that the labor itself both acknowledges and somewhat attempts to challenge by revealing his own labor. Editor: It's a complex dance on paper that reveals more than a few different tensions. It's also not separate from social tension, and by documenting the era he's complicit in the history. Curator: So, through Linnig's pen and ink, we witness not just a dance, but a confluence of artistry, social structure, and, potentially, the underpinnings of historical memory. Editor: Ultimately, viewing this pen-and-ink image invites contemplation of a romantic celebration and all that isn't contained by the image. It causes me to challenge whom and what we value culturally even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.