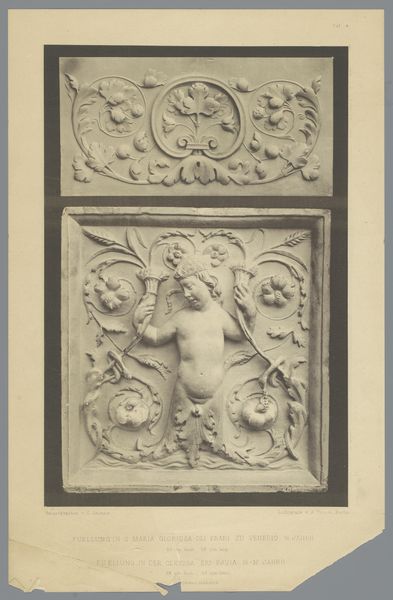

relief, sculpture, marble

#

medieval

#

stone

#

sculpture

#

gothic

#

relief

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

marble

Dimensions: overall: 45.1 x 35.3 cm (17 3/4 x 13 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have "Charity," a marble relief sculpture created around 1330 by Giovanni di Balduccio. Editor: It’s strikingly serene, almost ethereally white. The woman's upward gaze lends the whole piece a hopeful, pious feel. The texture seems smooth, cool. What was it like to see this when it was new, glowing white? Curator: Seeing this in its original context would indeed have been a powerful experience. Marble reliefs like these, situated within ecclesiastical spaces, reinforced societal values—in this case, the virtue of charity. Look at how the artist used gesture and inscription to create visual arguments of faith in the late medieval period. Editor: Inscriptions, yes, a scroll is right there—although the message has faded quite a bit, obscured. Her dress falls wonderfully though—simple, unadorned and pure white, the curves soft and sensual against the architectural grid. But let’s talk about the two children with her. What is going on there? The one she holds is almost deformed somehow…or damaged? Curator: Well, they were often presented with exaggerated features to highlight dependence on maternal figures, meant to underscore the virtuous acts of the central figure and those capable of providing succor. Charity extends from material goods to piety. Editor: Hmm, piety or guilt, perhaps. Does it show how the Church’s authority can intersect so directly in artistic representations, and how they manipulate emotional levers, maybe, to control wealth and power in the Republic? Curator: Yes, that touches on the intersection of religious, economic, and political forces that determined artistic patronage. This image served to shape and reflect civic virtues and beliefs about piety. It represents a larger system of symbolic communication during a time when visual imagery carried immense weight. Editor: A weighty burden indeed, carried in seemingly lightweight marble! Thinking about its social context has really brought it into richer, slightly uncomfortable focus. But a reminder—as many great art pieces do—that art, beauty, politics, power and beliefs, well, they’re all wound together pretty tightly. Curator: Absolutely, reflecting on that entanglement is vital. Thinking about artworks as a window onto the values and priorities of their time enhances our ability to understand not only the art itself, but the societies in which such compelling representations circulated.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.