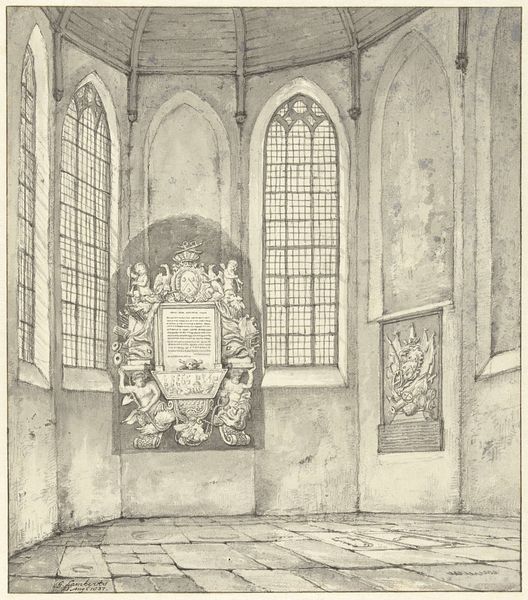

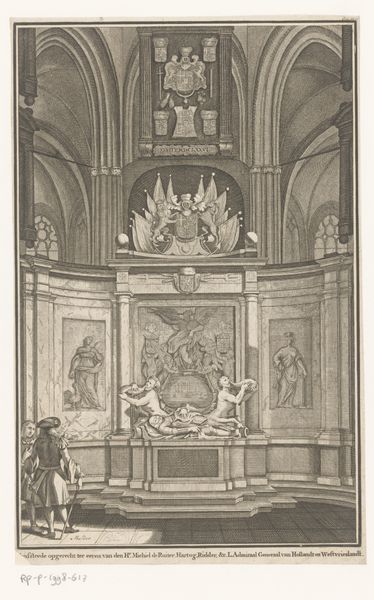

Grafmonument van Balth. Fredericus von Stosch in de Janskerk te Utrecht 1786 - 1850

0:00

0:00

gerritlamberts

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink, architecture

#

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

quirky sketch

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

geometric

#

architectural drawing

#

architecture drawing

#

cityscape

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 224 mm, width 276 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

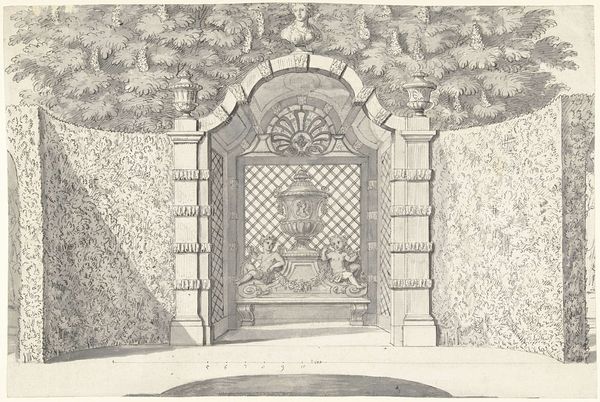

Editor: So, this is Gerrit Lamberts' drawing, "Grave monument of Balth. Fredericus von Stosch in the Janskerk in Utrecht," created sometime between 1786 and 1850. The Rijksmuseum holds it. It’s ink on paper, a fairly muted palette...almost ghostly, really. I am immediately struck by the stark geometry, yet also this strange domesticity due to the half opened door in the drawing, and, obviously, the scale of the depicted funerary sculpture, that dwarfs its immediate vicinity. How do you see this piece within the history of funerary art and its role within society at that time? Curator: It's fascinating how Lamberts captures the tension between public commemoration and private grief, isn't it? The monumental tomb situated within the domestic framing that you pointed to makes a compelling example for the history of Dutch Neoclassicism. It emphasizes rationality, order, and civic virtue that resonated with the ideals of the Enlightenment while it grapples with how political change disrupts existing social, familial hierarchies. Notice the somewhat muted or 'aged' colour palette, achieved using simple ink and toned paper which enhances the scene’s gravity. But how does that compare to the real site in Janskerk in Utrecht? How would you perceive that architectural site when facing that monument? Editor: I suppose in reality there is always going to be less quiet contemplation than one assumes when encountering artworks within institutions that were conceived long before being reappropriated to galleries or collections… So how much do you think that institutions and architectural contexts enhance or change the interpretation of the art itself? Curator: It is important to remind ourselves that the museum space fundamentally alters how we, as viewers, interact with and understand works that were once displayed in, and designed to belong to, spaces with clearly articulated political agendas and ideological purposes. This monument now prompts reflection on memory, power, and shifting values across centuries but always under contemporary agendas. The location becomes a site in and of itself... Do you see what I mean? Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about the context changes everything. Thank you, that’s something I will continue to keep in mind!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.