Copyright: Public domain

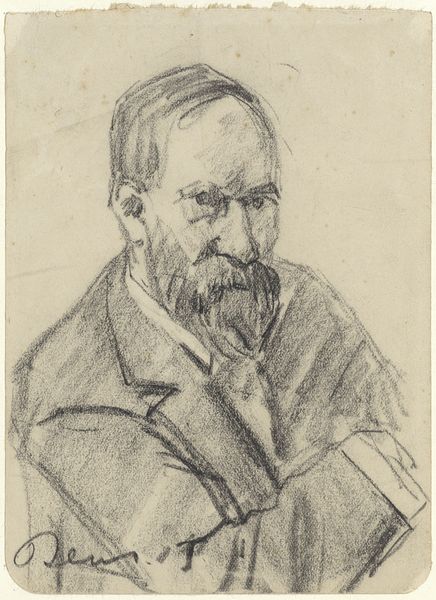

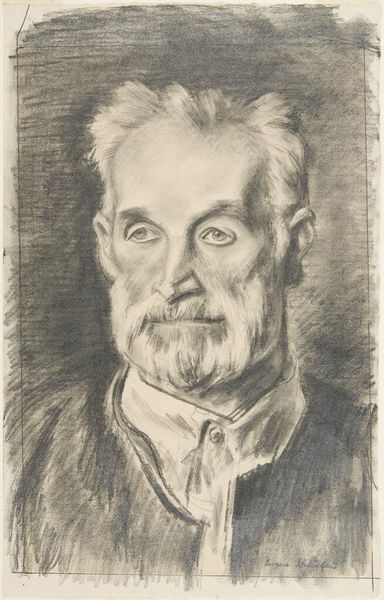

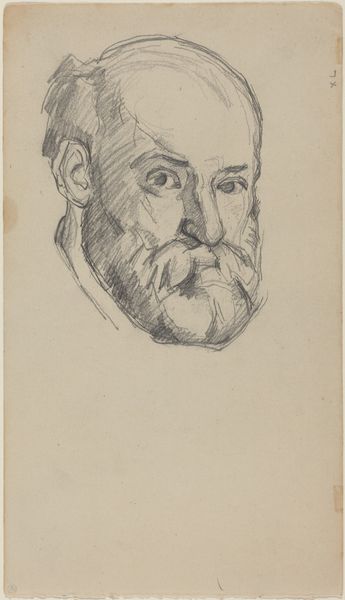

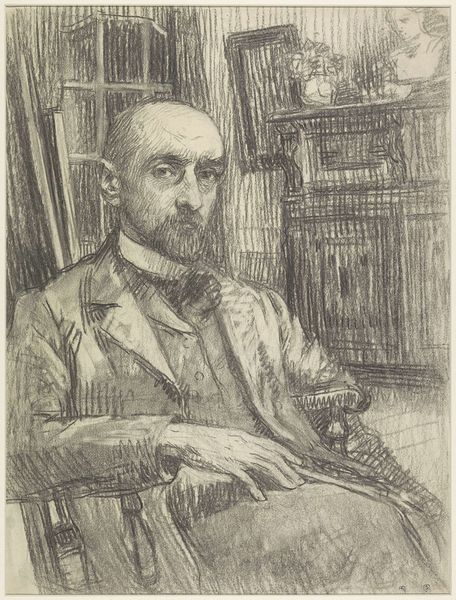

Curator: Maximilien Luce's 1898 pencil drawing, "Portrait of Henri-Edmond Cross," seems to capture a moment of quiet contemplation. What leaps out at you initially? Editor: There’s a kind of weary defiance in the subject's eyes. I read that as an active choice, maybe resistance. But also, the contrast of those sharp eyes with the flowing, almost dreamlike rendering of the beard... it suggests conflicting layers, wouldn't you say? Curator: Absolutely. It feels like Luce is peering beyond Cross’s external image, maybe searching for that spark, that individual character. He's known for capturing the everyday realities of the working class, so to see this more intimate portrayal of another artist... it is intriguing. The pose, the angle... it seems less about portraying status and more about understanding the person. Editor: Yes, and speaking of understanding… This drawing lands amidst a moment of heightened socio-political tension in France. The Dreyfus Affair, anxieties about class… how might Luce's own socialist leanings influence how we should interpret this “quiet contemplation," as you call it? Curator: Well, the intensity of the gaze does prompt questions, doesn't it? Knowing Luce’s political background adds layers to how we see the artwork; maybe there’s some deep questioning in those eyes. However, there's this undeniable humanity that surfaces, right? Just this feeling of empathy radiating out of the drawing. I can sense, in that particular moment, that they saw one another. Editor: But who are they “seeing?” A fellow artist? A fellow human? Or simply a fellow white male? To what extent does the lens of privilege determine the bounds of empathy available to both the artist and his subject? The technique, while beautiful, also reinforces certain canons of portraiture, historically unavailable to, say, women or people of color. Curator: Yes, certainly a point well worth pondering. It does highlight that tricky area where art exists both as individual expression but simultaneously mirrors the wider frameworks. Anyway, this piece stays with you, like a melody hanging in the air. It is, fundamentally, the study of a very specific relationship, viewed through a pencil and paper, which always retains the ability to intrigue and bring us back for another look. Editor: Right. The intimacy that you described is definitely potent, if also inflected by power dynamics we must remain aware of. It’s a powerful piece precisely because of the questions it provokes and the historical and societal contexts in which it was made.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.