Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

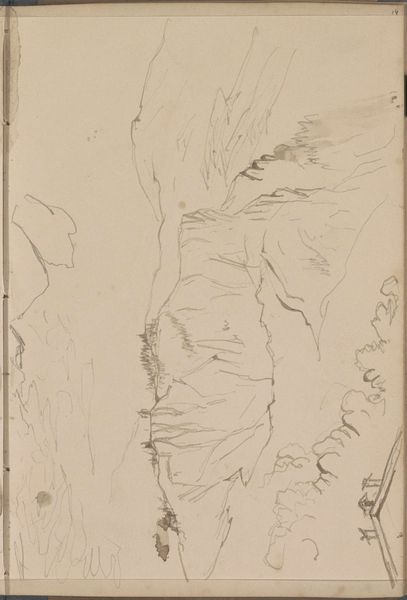

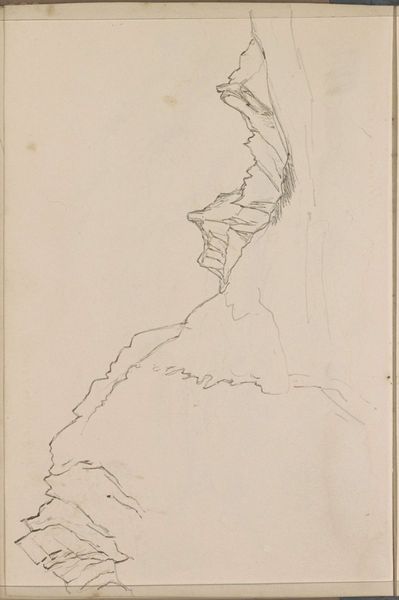

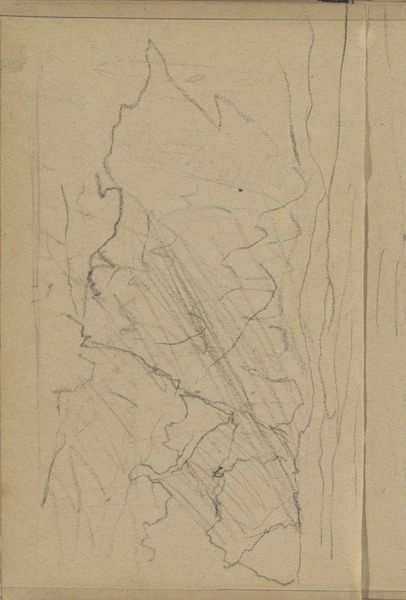

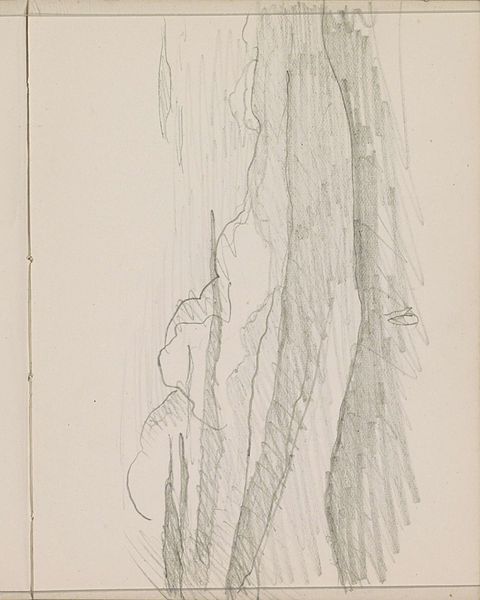

Curator: This pencil drawing is titled "Bos" (Forest) and it's attributed to Johannes Tavenraat, dating from sometime after 1854. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate response is one of quiet contemplation. The subtle pencil lines give it an ephemeral, almost dreamlike quality. There’s something both delicate and immense in the suggestion of a forest. Curator: Considering its probable date of creation, we might look at this piece through the lens of Romanticism. Nature, particularly the forest, was imbued with notions of the sublime, evoking feelings of awe, insignificance, and spiritual connection. Editor: Absolutely. And think about the symbols within the forest: the path, the hidden spaces, the overarching canopy. Forests in folklore are transformative spaces, places where identities are forged, tested, and redefined. They exist in the collective psyche. Curator: That makes me wonder, considering the time and location of the artwork's origin, if we can explore its connections to environmental movements that have used forests as spaces of activism and resistance. The struggle to maintain the sacred within nature—even sketched nature. Editor: It strikes me how unfinished the drawing feels. Note the contrast between the more detailed foreground trees and the almost vaporous quality of the background. It could suggest the limitations of human perception when confronted with nature’s grandeur. The visual impact carries an incomplete memory of nature. Curator: Perhaps it suggests the industrial revolution, too, and the impact it had on both lived experience and aesthetic representation. Editor: A potent observation, since we read of a historical rupture in the landscape and the perception of nature. Do you consider that an absence could represent the losses of that same progress? Curator: Certainly. These works prompt discussions of what's included, and what's notably left out. And beyond mere natural depictions, it is vital to address the power structures and the politics ingrained in them. What kind of forest is not depicted here, and what communities are denied representation within this aesthetic tradition? Editor: I’m thinking again about how the very act of sketching preserves an individual's impression of this space. And I appreciate seeing this visual encoding from the nineteenth century. Curator: Understanding it is crucial, precisely because it also invites interrogation. I wonder, in examining how it continues to resonate today, how we can create broader, more inclusive dialogues around both artistic representation and ecological consciousness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.