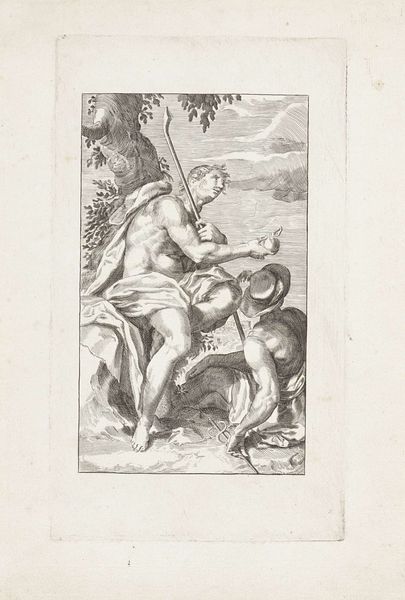

engraving

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

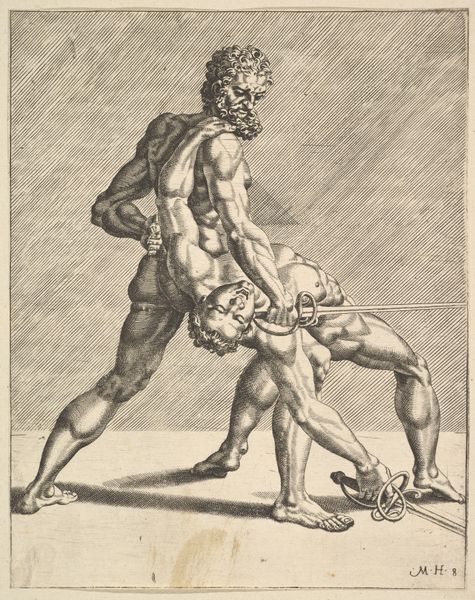

engraving

Dimensions: height 255 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Cornelis Bos's engraving "Two Swordsmen," created in 1552. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum. The immediate tension of the depicted combat is quite arresting. Editor: Yes, that initial impression is striking. There’s a raw intensity, a certain vulnerability conveyed through the very lines etched into the metal. Curator: Bos, working in the Mannerist style, really emphasizes the artificiality, even the performance of masculinity. Note the exaggerated musculature, the stylized poses – it's almost theatrical. This theatricality hints at broader narratives concerning power and control. The subjugation visible here can reflect power structures and social hierarchies of the period, wouldn't you say? Editor: Indeed. And the materiality itself speaks to that. Engraving as a reproductive medium allowed this imagery to circulate, almost like propaganda – disseminating specific ideals about strength and dominance across a wide audience. Who were these men supposed to be? How are swords, tools of combat and also of display, rendered here? The precise cuts of the engraving tool mimicking the cuts they inflict? Curator: The men could represent a number of things. It's worth bearing in mind the role of fencing as an elite pursuit at the time, often linked with nobility and codes of honour. And yes, the craftsmanship further elevates these figures. Editor: Look at the lines themselves. The physical act of engraving, cutting into copper, producing images of struggle... that connection between material and subject matter cannot be ignored. The cost to acquire such engravings limited consumption, and therefore regulated visibility of the violent action depicted. Curator: I agree that it's an interesting relationship. Looking at it with an intersectional lens, how might notions of masculinity, violence and artistry come together in ways that speak to a more complex construction of gender and power? How does the act of creating such images, which lionize dominance, serve and perhaps even consolidate structures of violence in broader society? Editor: And considering this was meant for dissemination—for reproduction— the material considerations speak to the economics of art-making in the period, raising key questions of labor and skill, also underlining how distribution of the artworks contributes to, or actively works to shape its social meanings. Curator: Exactly. It leaves one wondering what reception the image generated then, and the work that these engraved lines continue to do today in circulating ideals of violent masculinity. Editor: Absolutely. Examining the materiality, the choices in labor, and their consumption provides yet another lens. I leave here with more than only what meets the eye in combat, but what has escaped from these fine cuts!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.