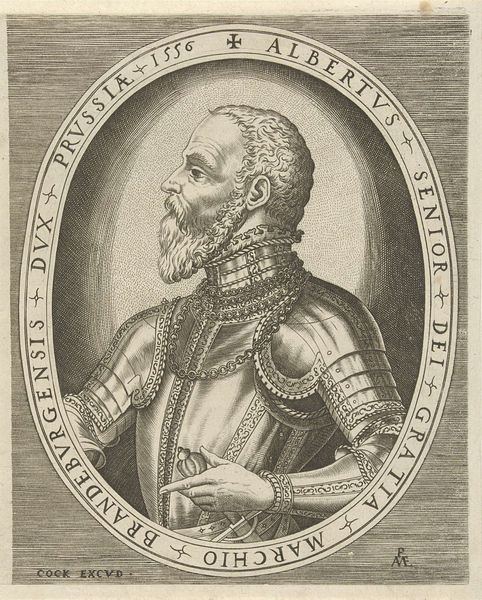

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

11_renaissance

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 314 mm, width 219 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a rather striking engraving titled "Portret van Karel V van Habsburg," estimated to have been created sometime between 1546 and 1562, credited to Frans Huys. It currently resides in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, what grabs me is the sheer amount of texture achieved through engraving. The detail on the armor, the rendering of flesh... it really speaks to the skill and labor involved in this printmaking process. Curator: Absolutely. Engraving lends itself well to the creation of pattern and a precise quality of line, and here we can appreciate the Mannerist influence. The surrounding allegorical figures feel quite elaborate, creating a circular framing, further emphasizing Charles' role in earthly dominion and likely intended to emphasize his piety. He is holding the orb of earthly power in one hand, but his sword crosses right in front of it! Editor: Right, that sword can be understood as one of the essential tools and technologies used by the ruler. But those female figures around the border? How were the reproductive means and patronage that sustained workshops linked to such aristocratic productions? That inscription on the bottom might yield more information about where this image came from. Curator: Precisely! Notice, for example, how Charles holds a sword, visually intersecting a terrestrial globe crowned with a cross, a bold declaration linking worldly authority with spiritual mandate. Even his stern visage underscores his unflinching commitment. One really feels the weight of the Hapsburg legacy! Editor: Well, the engraving format also speaks to circulation—printed images were far more easily distributed, democratizing access to the royal likeness and imperial authority, beyond painted portraits available only to the wealthy elite. Think about the markets, the workshops… the means of dissemination were as crucial as the message itself. Curator: Fair point. The print as a material object does democratize viewership; in doing so, we come to acknowledge a different sphere of Charles’ reach that moved beyond geographical dominion to image economy and visibility, which, to be fair, remains an important attribute of power to this day. Editor: Looking at it this way allows us to understand how this was a functional item as well as a striking image. It reflects the very process of image making and its significance in Early Modern Europe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.