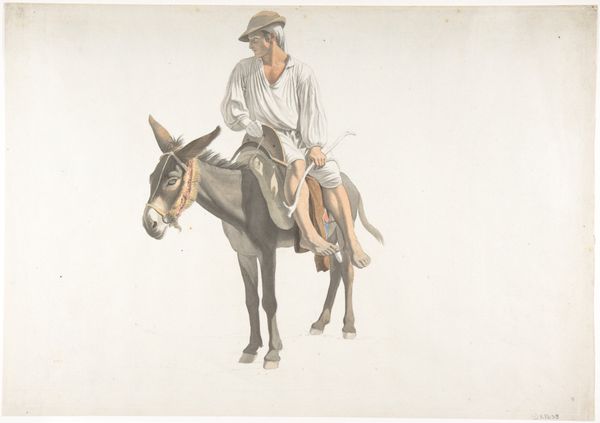

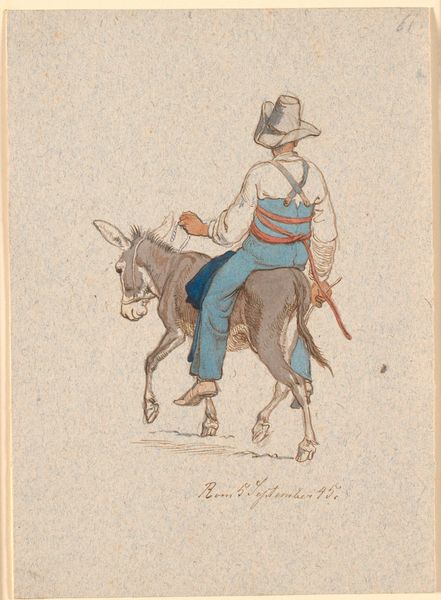

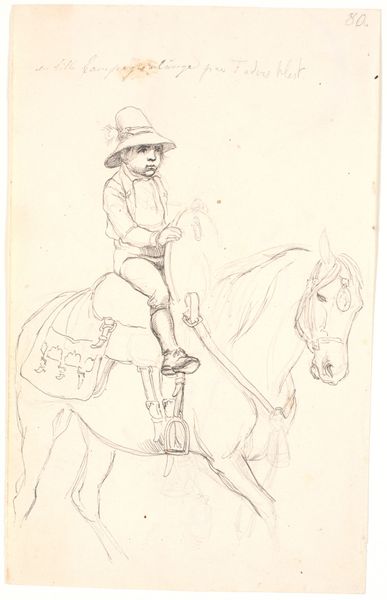

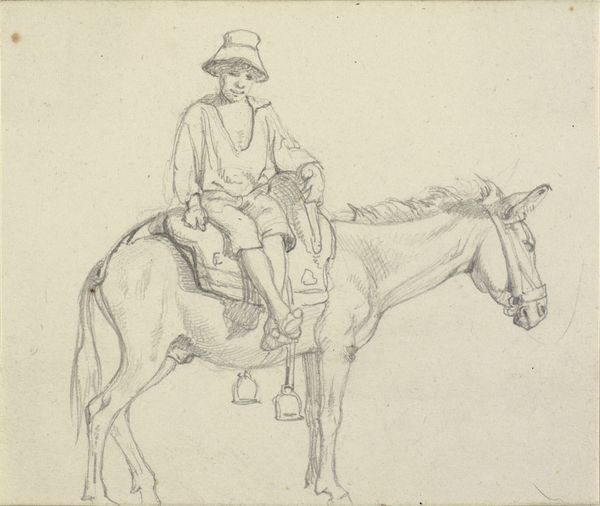

En italiensk bonde med hans søn, siddende på et æsel 1846

0:00

0:00

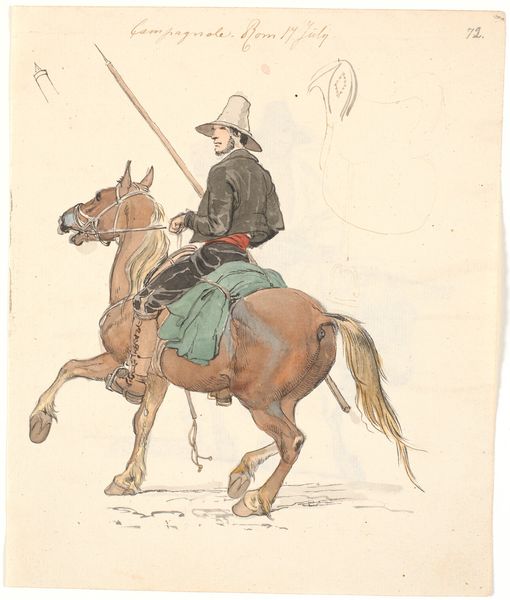

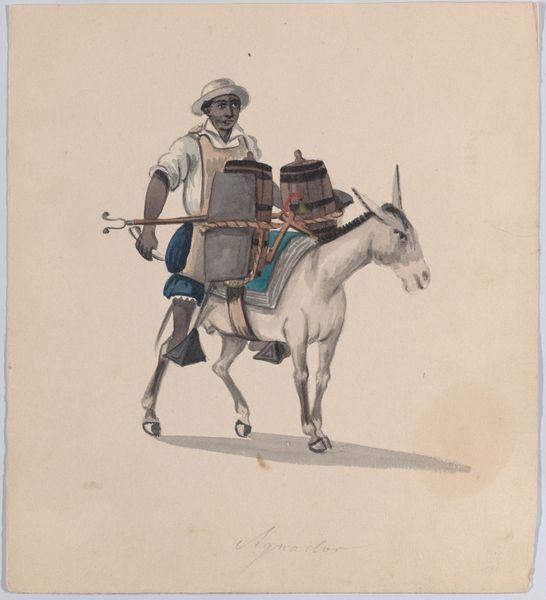

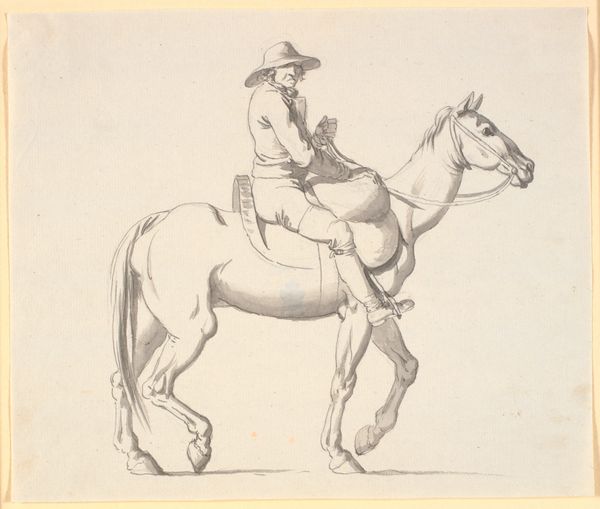

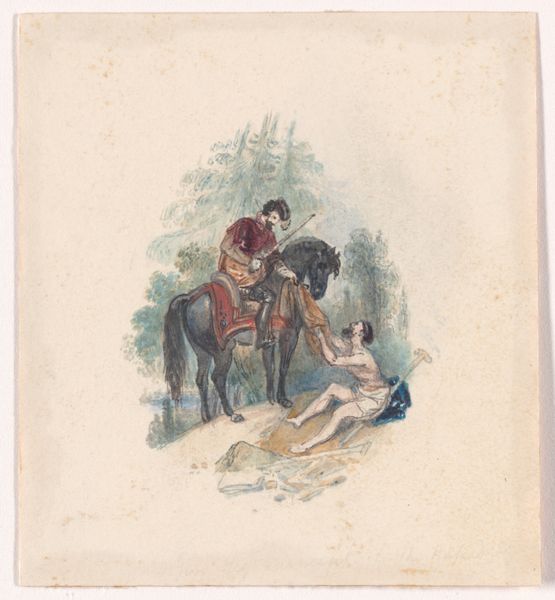

drawing, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 171 mm (height) x 212 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Johan Thomas Lundbye's watercolor drawing, "An Italian Farmer with His Son, Sitting on a Donkey," created in 1846, offers us a glimpse into rural life through a Romantic lens. What's your first take? Editor: The delicate washes give it a sense of sun-drenched stillness, doesn’t it? And the almost caricatured figures invite an immediate connection. What can you tell me about the context? Curator: Absolutely. Lundbye was part of the Danish Golden Age, when artists sought inspiration in both national identity and wider European culture. Italy, of course, was a popular destination. He's portraying, in a sense, an idealized peasant class. His work fits into a larger narrative that involves themes of social justice, and how identity gets represented. These peasants of Southern Europe, often rendered through idyllic, soft painting styles. Editor: The donkey, naturally, would immediately evoke the biblical connotations of humility and poverty. Its representation here makes me think about art historical trends representing farm animals over centuries: it feels related, even distantly, to images of the Holy Family traveling on donkeys. Curator: Good point. While these tropes existed, there's the critical aspect to consider too. It raises questions: what does it mean for a relatively privileged Danish artist to depict the daily lives of Italian peasants? Are we truly getting an unvarnished glimpse of reality, or is Lundbye reinforcing class divisions? Editor: It does provoke consideration on multiple symbolic levels. You know, from their somber, slightly world-weary expressions to their sun-baked skin tones, they communicate both hardship and perhaps a quiet resilience. The son, with his red hat, mirrors in the overall color story to that of the father’s draped garment—perhaps reflecting cycles of inherited identity. Curator: I agree. The work becomes not just a landscape piece or genre painting, but a study in cultural representation and perhaps a critical engagement with notions of privilege. How do we view art, and the gaze through which we approach this representation? Editor: Ultimately, images like this compel us to keep reassessing how visual representation informs identity and memory. It certainly encourages a richer interpretation of our shared, visual past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.