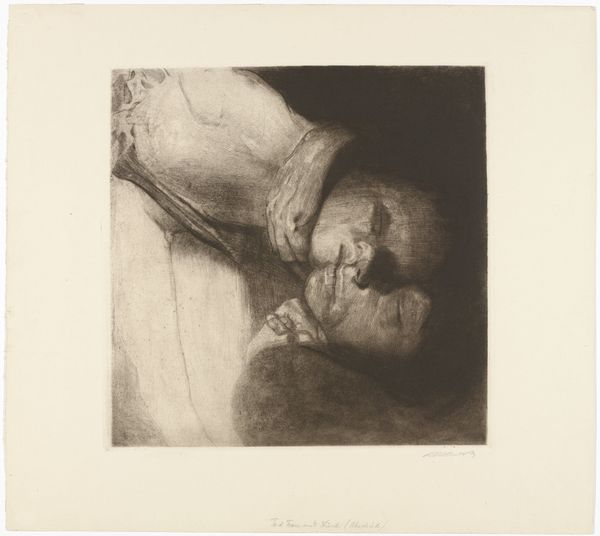

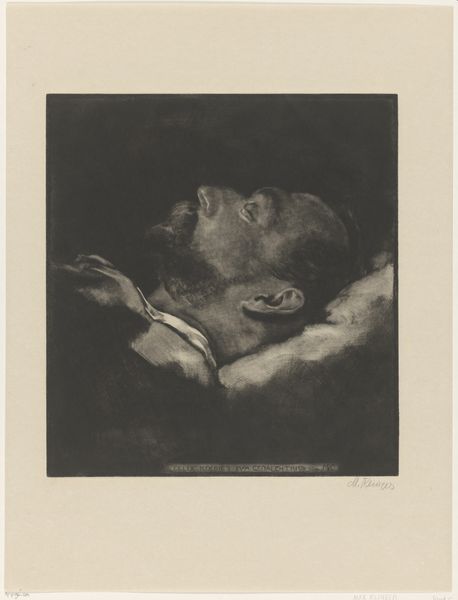

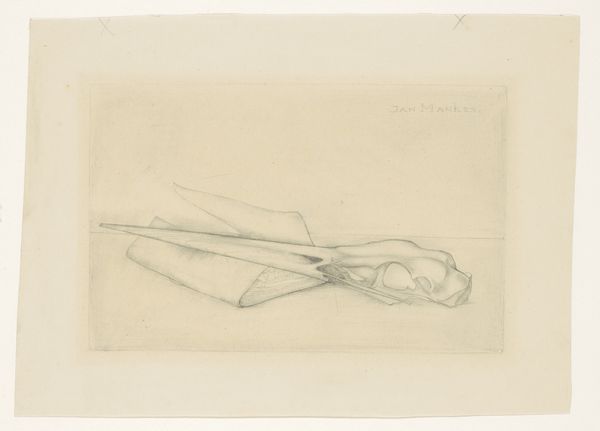

Portret van Johann Heinrich Lavater op zijn doodsbed 1775

danielnikolauschodowiecki

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 152 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki’s engraving, “Portret van Johann Heinrich Lavater op zijn doodsbed,” created in 1775. The piece resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: What a haunting image. It’s stark, intimate—you can almost feel the stillness in the room. It makes you confront mortality head-on. It reminds me of that sensation you get in that small hours of the morning before the world wakes, and for a moment it feels as if time has briefly ceased its march forward. Curator: Indeed. The work serves as a poignant visual document. Lavater, a prominent Swiss pastor and theologian known for his work in physiognomy, which is a now debunked, pseudoscience involving deducing character from facial features, and the artist Chodowiecki were acquainted, giving this portrayal an even deeper layer of significance. Editor: It makes you wonder, doesn't it? Was this some form of post-mortem analysis using physiognomy? What can we glean, or what did they hope to glean, about Lavater's life through this final repose? Did he have any final reflections that Chodowiecki might have wanted to immortalize? The subtle use of light and shadow really accentuates the stillness of his features. It's a very arresting artistic choice. Curator: Art and death have been intertwined throughout history, and during the 18th century, there was a growing interest in portraying death in a realistic and, at times, sentimental way. Prints such as these allowed for the wider dissemination of such imagery, solidifying a person's legacy but also shaping public sentiment and memory. Editor: There's something undeniably sacred and respectful about it though. I almost feel as if I am intruding. It gives you an impression of the weight of silence that occurs in the aftermath of a death. He isn’t just a figure, or even just a notable theologian; he is a person laid bare, devoid of artifice, making him… just, real. Curator: It encapsulates the historical and artistic currents of its time. Beyond just a portrait, it embodies the evolving ways society sought to come to terms with the inevitable end, capturing more than just an image. Editor: Agreed. It's not simply a portrayal of death, but an artifact that resonates even now with considerations on life, loss, and remembrance. I like that a lot.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.