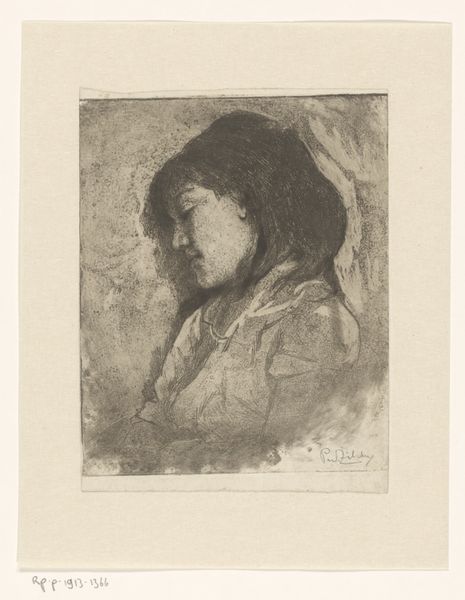

Dimensions: 55.6 x 61.2 cm

Copyright: Public domain

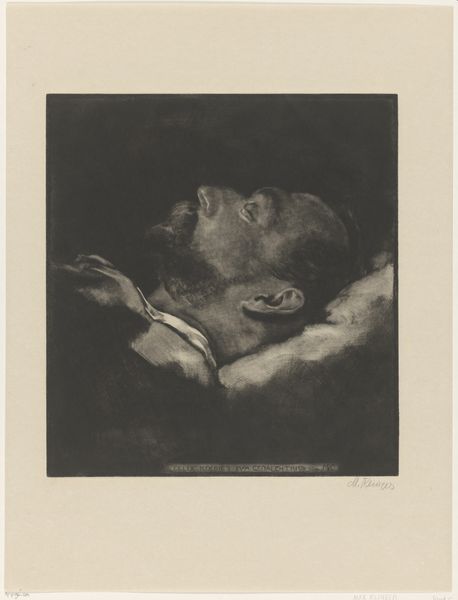

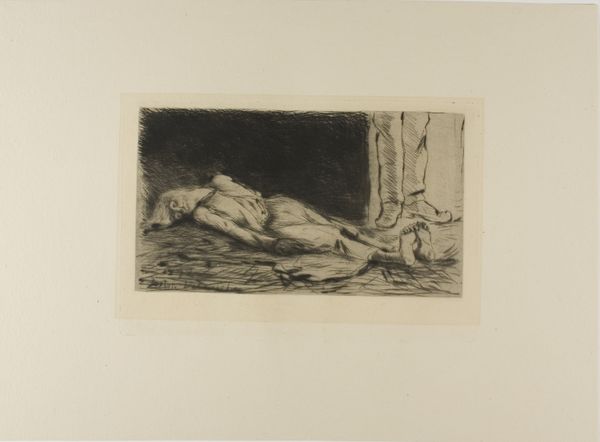

Curator: This is Käthe Kollwitz’s etching from 1934, "Death, Woman, and Child," currently held at MoMA. The somber tonality and intimate scale create an immediate impression, don't you think? Editor: Yes, a deeply unsettling mood pervades the entire scene. It’s raw, stark, and profoundly human in its depiction of despair. Kollwitz was working during a turbulent period in German history; can we delve into those themes of trauma and grief reflected here? Curator: Precisely. Look at the composition, how Kollwitz uses line and shadow to construct a claustrophobic space. See how Death looms over the figures? His stark face obscures a full appreciation of the maternal protection. It's a masterful exploration of light and dark, visually expressing internal psychological turmoil. Editor: The etching's stark contrasts serve as a visual metaphor for the political and economic instability that ravaged Germany at the time. One sees her own son's death during WWI echoing powerfully, channeling the trauma of war and poverty experienced disproportionately by women and children. Curator: One might argue her mastery lies not just in documenting social realities, but also transforming lived experience into a potent visual language. Editor: I see more of a feminist analysis, observing a critique of patriarchal systems through these brutal realities. The piece is, through the German Expressionist idiom, a mirror to society. Consider her choice of printmaking—a medium accessible to many, thereby turning it into an intrinsically democratic art form. Curator: That emphasis underscores her political commitment but I contend we shouldn’t sideline her formal skills and unique visual approach; note the textured layering and angular compositions throughout her career. Editor: I agree to an extent, but it's precisely that marriage of form and sociopolitical messaging which distinguishes Kollwitz’s position. Understanding art means engaging these multiple registers; form cannot exist in some aesthetic vacuum. Curator: Indeed. Reflecting upon Kollwitz, we're challenged to view history not as some detached record but an echo we see through the artist’s capacity to transform pain and loss into an act of creative agency. Editor: Precisely—to see within “Death, Woman and Child” not only a reflection of its era, but its ability to inspire resistance in the present and empathy with other social actors for all viewers to encounter.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.