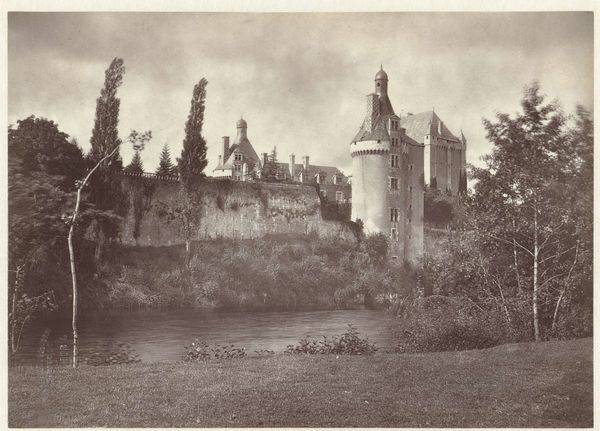

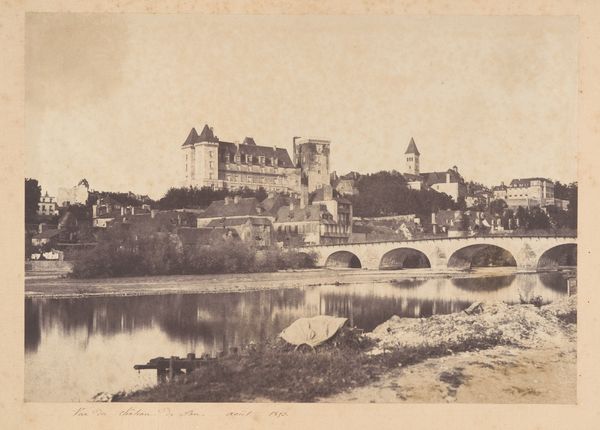

Dimensions: height 153 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

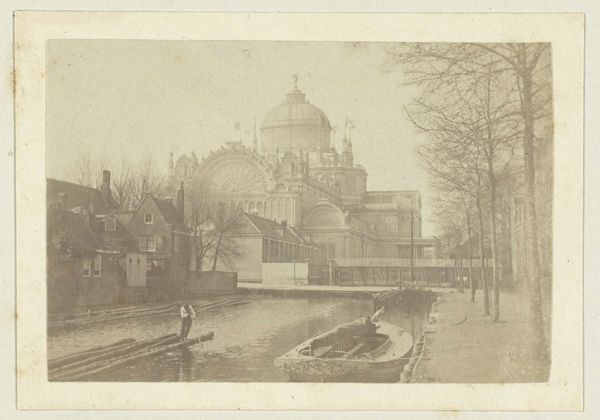

Curator: What a strikingly composed photograph. The stillness of the water juxtaposed with the imposing structure... Editor: Indeed. We're looking at a gelatin silver print by Jules Robuchon, dating roughly from 1880 to 1886. It’s titled "Besneeuwd Château de Touffou in Bonnes, Frankrijk," capturing the chateau under a blanket of snow. The choice of the gelatin silver process speaks volumes about accessibility; by this period, it was becoming more industrialized, and less reliant on individual artist control, yet offers remarkable detail. Curator: The formal arrangement is exquisite. The bare tree in the foreground acts as a framing device, drawing the eye towards the chateau. The water mirrors the scene, creating a sense of depth and almost ghostly duplication. It really emphasizes the structure and massing of forms. Editor: I am compelled to think about the conditions of its production. Consider Robuchon traveling, burdened with equipment, and potentially darkroom necessities in order to make these prints on site. What was his social position, how did this project relate to that identity, and, subsequently, who could view it? Photography by this time, was still an art of labor and materiality that involved a considerable level of preparation and consideration beyond merely taking an image, unlike say a digital photograph today. Curator: That’s a great point, and I completely agree. Despite these cumbersome means of creation, what stands out for me is its emotional register. The scene is rendered with subtle tones. I find it melancholy, almost Romantic in its treatment of light and shadow, and use of pictorial space. It is visually intriguing; those muted tones enhance the architectural forms and their imposing nature in the landscape, softened by winter. Editor: I’d add that such views romanticize not just nature but also feudal structures. One is prompted to look at an idyllic snowy picture and is implicitly forced to think, “who maintained that picturesque location?” Who cleared that path in the winter and lived in relative comfort compared to others that might have maintained this “artistic” site in the picture? How the wealthy elite enjoyed landscapes purchased at a massive surplus value of labour from others, for the sheer sake of “the look?” That image, I posit, can’t truly be separated from this picture’s history of power and extraction. Curator: Certainly, it offers more than meets the eye, prompting reflection on how it was made and circulated. Editor: Agreed; examining its mode of production is crucial.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.