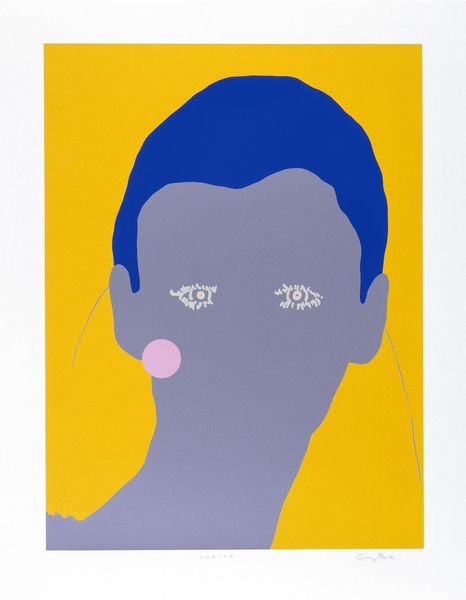

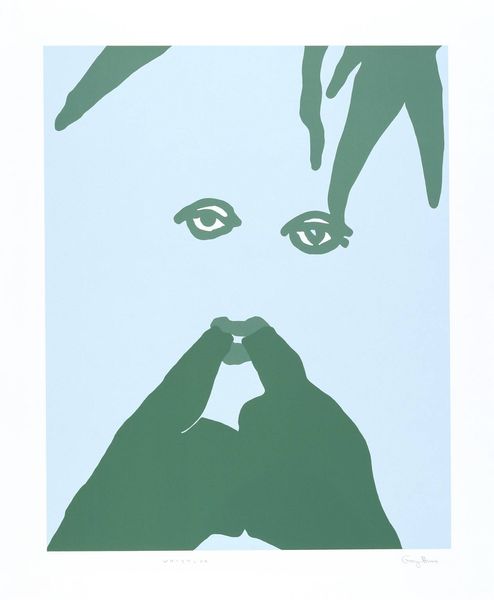

Dimensions: image: 909 x 633 mm

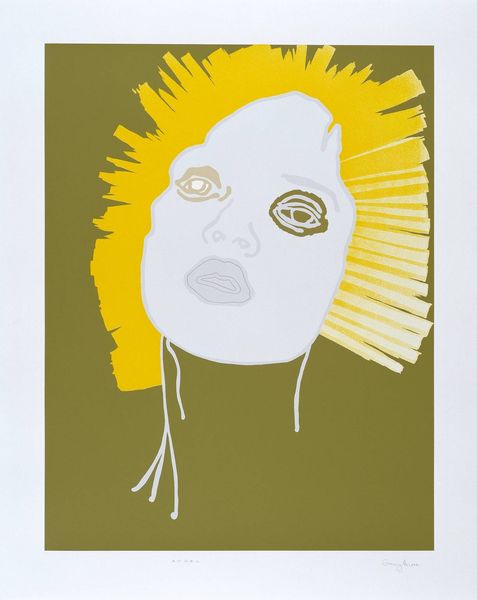

Copyright: © Gary Hume | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

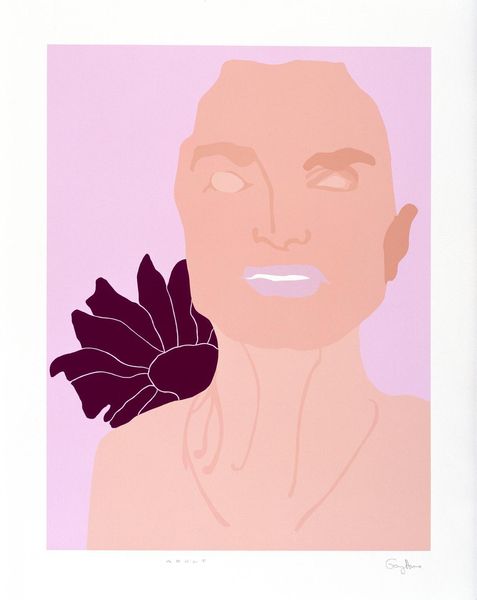

Editor: Here we have Gary Hume’s "Lady Parker." It’s quite striking, a portrait rendered in flat planes of lilac and gold. What can you tell us about the context of this piece? Curator: Hume's work often engages with ideas of celebrity and the objectification of women. Consider how the simplification of Lady Parker's image—the flat color, the minimal lines—might comment on the way female figures are reduced to commodities within popular culture. Editor: So, is Hume critiquing the media’s representation of women? Curator: Precisely. He presents us with a flattened, almost generic image, prompting us to question the gaze and the power dynamics inherent in portraiture and celebrity culture. What does the color choice suggest to you? Editor: The lilac feels almost artificial, maybe highlighting the artificiality of the image itself. Curator: Exactly. It invites us to consider how these constructed images shape our perceptions and expectations of women. Editor: I hadn’t considered all the layers of social commentary. Thanks! Curator: It’s crucial to explore those layers and challenge the status quo!

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Hume’s Portraits is a series of ten screenprints commissioned by Charles Booth-Clibborn and published by him under his imprint, The Paragon Press, London. They were proofed and printed at Coriander Studio, London in an edition of thirty-six plus ten artist’s proofs. Tate’s copy is number eighteen in the edition. Each print was made using between three and fifteen colours and coated with several layers of varnish in sections. The varnish results in a sheer, glossy surface similar to that achieved by Hume’s use of household gloss paint in his paintings such as Incubus 1991 (Tate T07184) and Water Painting 1999 (Tate T07618). The prints are based on paintings Hume made between 1994 and 1998. Some of these paintings were derived from photographs, others from Hume’s imagination. Each print has a subtitle related to the original painting. This is the seventh image and its subtitle is Lady Parker. It is based on a much larger painting, Lady Parker (After Holbein) 1998 (Guy & Annushka Shani, London) in gloss paint on aluminium panel. It differs from other images in the series in consisting mainly of drawn lines on a flat monochrome pink background rather than areas of flat colour. In the painting the lines are grey; in the print they are pale blue, with a darker shade of blue used to delineate Lady Parker’s eyes. Two geometrically perfect black discs on either side of her face in the painting have been replaced by larger pale yellow discs on the print. These discs, possibly representing earrings, constitute the most radical aspect of Hume’s transformation of the original. As the painting’s subtitle explicates, the image is based on a portrait attributed to German-born painter and official portraitist in the court of King Henry VIII, Hans Holbein (the Younger, 1497-1543). Holbein’s drawing of Lady Parker (thought to be Lady Grace Parker, who was married to Sir Henry Parker in 1523 at the age of eight) is one of his most popular images available in reproduction. Hume has depicted her in renaissance costume in the style of drawing typical to contemporary cartoons or fashion drawing.