print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

perspective

#

cityscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 490 mm, width 714 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

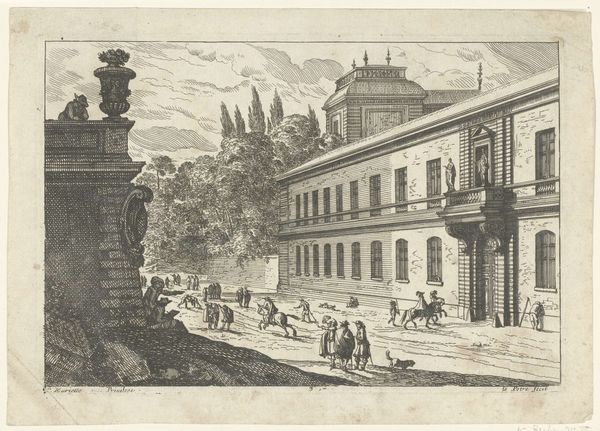

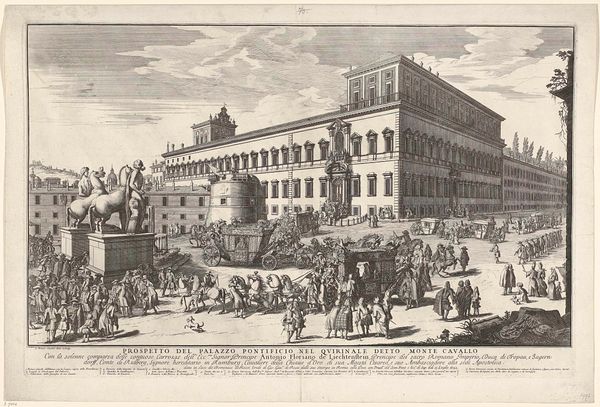

Curator: Looking at Jan Lamsvelt's "Twee gezichten op Palazzo Montecitorio te Rome," from 1724, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, one is struck by the sheer scale and ambition conveyed through this print. What's your initial read on this architectural rendering? Editor: It's strikingly cold. Despite the people scattered throughout the courtyard, it feels almost desolate. The architecture dominates everything, dwarfing the human figures and creating a sense of alienation. There is also something unnerving in the mirror presentation, one perspective mirroring the other. Curator: The artist is very concerned with how state power is viewed and felt. Lamsvelt captures two perspectives of the Palazzo, emphasizing its role as a seat of authority, a very important piece of architecture that began construction in 1650 and remains important to this day. Its design evolved significantly from Bernini's initial plans and shows several Baroque features. Think about how the engraving would've functioned for those who may never visit Rome, in establishing a grand image of authority. Editor: Exactly, this wasn't just a representation of a building; it was about projecting power and legitimacy. And the architectural perspective itself plays into that, doesn't it? The linear perspective and symmetry create a sense of order, control, and permanence. Look how this perfect vision denies space for dissent and celebrates hierarchy and control. I'm also interested in what isn’t shown; who truly benefited from its halls, and what may those beneficiaries have left behind? Curator: Those are critical lenses to examine the work. Considering Lamsvelt's role within the artistic and social circles of the time is paramount to a full understanding. The choice to portray the Palazzo in this manner also aligns with the period's fascination with civic pride and projecting strength through architectural prowess. What might this sort of print have represented for the people in Amsterdam during this period? What would they have gleaned from these halls? Editor: Well, to your point on civic pride, it feeds into the colonial mentality, as well. Images of grand structures in colonizing nations create impressions, and function as psychological warfare against those subjugated by those powers. And as this type of perspective became standard for propaganda in service to the state, what sort of accountability would it suggest to reimagine public works from the bottom up? How can a critical eye change the ways an institution behaves? Curator: A very pertinent provocation to reconsider, especially when observing today's power dynamics that continue to favor hierarchical designs. Thank you, this has offered much to think about. Editor: Agreed, looking at this piece through a modern perspective helps highlight the continued power and influence architecture can have over our perception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.