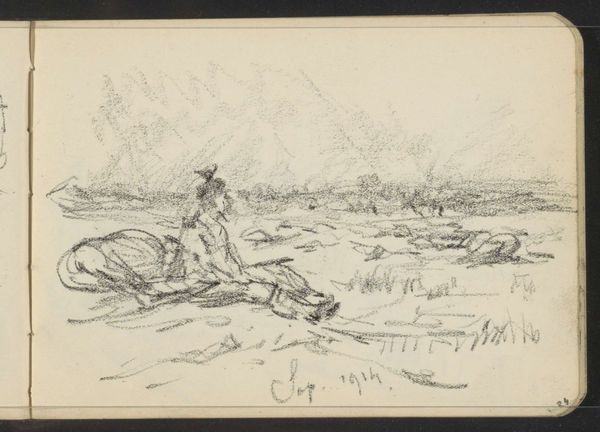

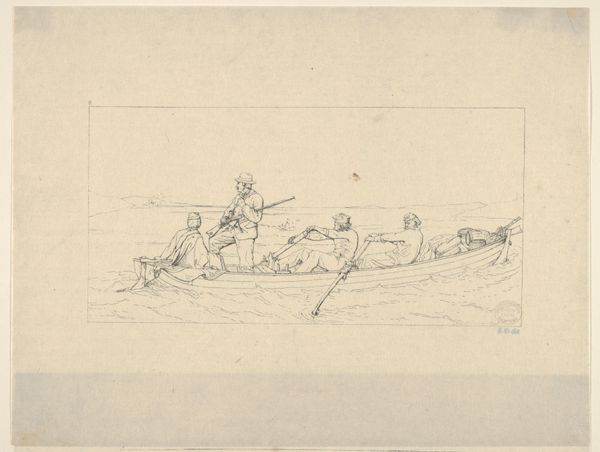

Bjergrigt landskab med en kirke (fortsat fra forgående side) 1835

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Dimensions: 137 mm (height) x 211 mm (width) x 10 mm (depth) (monteringsmaal), 137 mm (height) x 211 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Looking at this landscape drawing by Martinus Rørbye, titled "Mountainous landscape with a church," dating back to 1835, it feels immediately like stepping into a sun-drenched daydream, doesn't it? All shimmering water and distant hills. Editor: Indeed, what's compelling is Rørbye’s emphasis on process; this isn’t a finished painting destined for a salon, but rather an intimate pencil drawing. You can almost hear the scratching of lead on paper, sense the artist capturing the immediacy of his surroundings. Curator: Absolutely! It's a romantic snapshot. See how he's perched the figure, almost casually, against that backdrop of hazy mountains? It whispers of freedom and exploration. It reminds me a little bit of Kerouac. I wonder, was it just a study, or was it trying to capture the immensity of nature, a divine spark in the ordinary? Editor: The bare materiality of the pencil suggests its own narrative. Consider Rørbye’s choice to draw such a vast, idealized scene using such humble materials—the very tools of early industrial labor. And consider that the ‘romanticism’ is consumed now as something of great worth displayed on museum walls; it invites us to question how objects become valuable. Curator: A beautifully grounded thought. It does offer this raw, sketch-like glimpse behind the curtain. It invites you into his process. Did you ever feel like you're capturing a lightning in a bottle when creating? It's almost a compulsion to transcribe and express before the moment flees. Editor: The real jolt is the visible trace of work. The ‘divine’ is not purely aesthetic but woven through production itself: sourcing the materials, honing craft, sketching lines to communicate meaning. That shifts our perspective. Curator: Well, it makes me reflect on my appreciation and my work itself. The simple act of pausing and really *seeing* something... It feels incredibly profound sometimes, doesn't it? Editor: Precisely, an art that comes alive precisely through our attentiveness, through an acute consideration of its conditions of being and becoming.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.