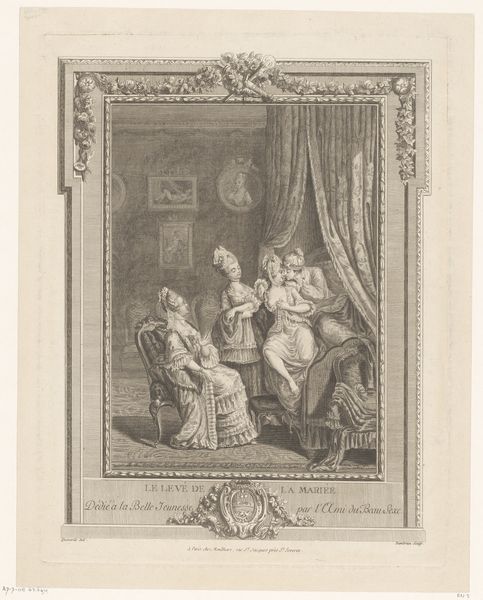

La Grande Toilette (The Patroness), from Le Monument du Costume 1777

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet: 12 11/16 × 10 3/16 in. (32.2 × 25.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's explore this engraving from 1777, "La Grande Toilette" also known as "The Patroness", created by Antoine Louis Romanet. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Well, immediately I see a snapshot of privileged life, rendered in delicate detail. There's a kind of theatrical artificiality that’s quite striking, bordering on parody of aristocratic ritual. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the toilette itself. Historically, the act of dressing, particularly for those in high society, transformed into a performative art. This image crystallizes the patroness' elevated social status—dressing became a public spectacle of power. The gestures within feel almost codified, symbolic. Editor: And those codified gestures smack of systemic inequality! A woman, likely of high birth, being prepped and primped by attendants... It’s a visual representation of a rigid social structure that prioritized appearances over equity and social progress. Look at the powdered wigs, the elaborate embroidery; these aren’t just details—they're symbols of exorbitant wealth contrasted against the impoverishment of the masses during pre-Revolutionary France. Curator: Yet those details speak to something deeper as well. Ornament and ritual create meaning, both within the moment for those performing them, and over time, culturally. Notice the way her gaze isn't directed at any specific person but looks off in the distance, creating a persona both tangible and distant. She almost blends with her surroundings: look how similar the wall decor's curvatures mimic her pose. What do you see there? Editor: I notice she appears oddly disengaged in the moment, perhaps burdened by the restrictions placed on women, on her performance of beauty as a form of social currency. She seems like a commodity herself in this scene. Curator: Possibly, though remember portraiture from this period served to project the ideal image of a sitter rather than documenting precise realism. It tells us more about societal values and less about a given woman's psyche. The objects mirror and candles reflect a life filtered through image and impression; appearances and roles that reinforced class power in tangible ways. Editor: But doesn't that precise filtering and mirroring itself betray an unease with reality? The fact they felt the need to curate and carefully perform these scenes speaks to underlying vulnerabilities and contradictions. I appreciate Romanet's precision, his documentation allows for dissecting and decoding of these symbols of excess, status, and performativity. Curator: Indeed, that sustained tension adds depth to this visual relic. We can feel how personal identity and societal artifice were so enmeshed. Editor: Agreed. These kinds of images prompt critical reflection; an engagement that transcends simply admiring a historical image. It calls on viewers to consider the lasting ramifications of such social hierarchies and unequal labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.