coloured-pencil, painting, watercolor

#

coloured-pencil

#

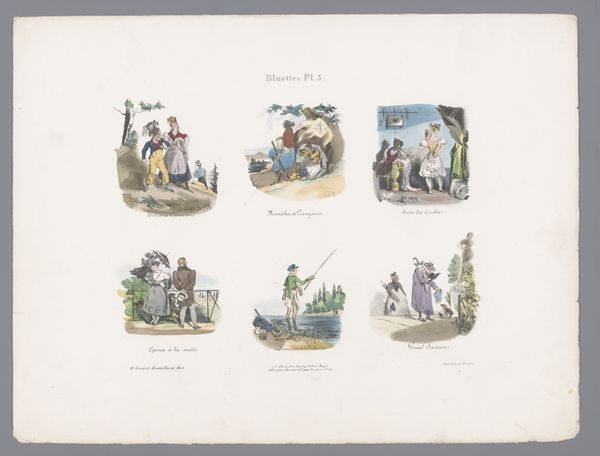

painting

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

folk-art

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 218 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

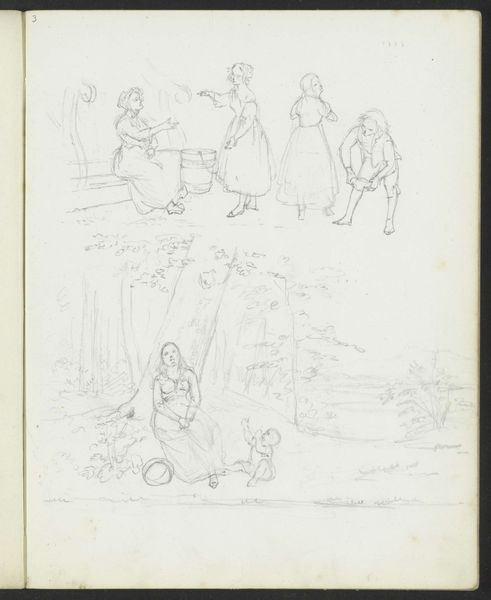

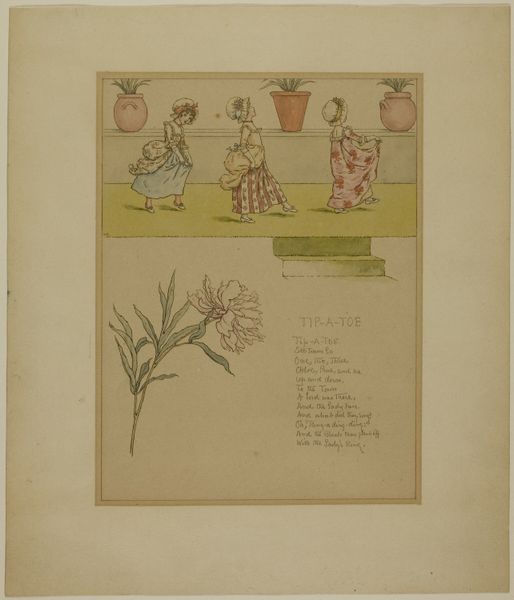

Editor: This is "Vijf proefdrukken voor de Almanack for 1887," which translates to "Five Proof Prints for the Almanac for 1887." It was made before 1886. The mixed media—watercolor and colored pencil—gives it a storybook feel. There’s a depiction of what seems like labor in a field in the image. How do you interpret this work through a socio-historical lens? Curator: It is tempting to read this work as a sentimental glimpse into rural life before industrialization. However, I suggest we examine these images not just for their aesthetic qualities, but as representations of labor and class. Consider the figures working the land; are they romanticized ideals of farm workers or accurate portrayals of lived realities? The style hints at folk art, often tied to community and tradition, but what social structures are subtly being reinforced here? Who is absent from these images? Editor: That's interesting! I was mostly drawn to the composition, but I didn’t really stop to think about the absence of other kinds of figures or who exactly the artist meant to portray. Could you tell me more about the kind of theory that you bring to a work like this? Curator: Think about intersectionality—how class, gender, and even age intersect in shaping individual experiences within these rural communities. Are we seeing a celebration of labor, or a glossing over the harsh realities of working-class existence? Does the medium—the gentle watercolor and colored pencil— soften a potentially critical perspective? Editor: So, you're saying that the 'folk-art' style and soft colours might mask underlying power dynamics? Curator: Precisely. It compels us to question whether this almanac reinforces dominant narratives about rural life and potentially obscures the complexities of class struggle during that period. Whose story is really being told and who is missing? What does it omit and how does it resonate with, or diverge from, contemporary discussions about labor and social justice? Editor: Thank you; it’s changed my initial perspective. Now, I am viewing it as less of an innocent folk scene and more of a curated presentation of certain ideals. I’m leaving this interaction with a new awareness of art’s potential as a vehicle for understanding the intersections of culture and class. Curator: Agreed. Art isn’t created in a vacuum and taking a contextualized view such as this, we can see beyond the face value!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.