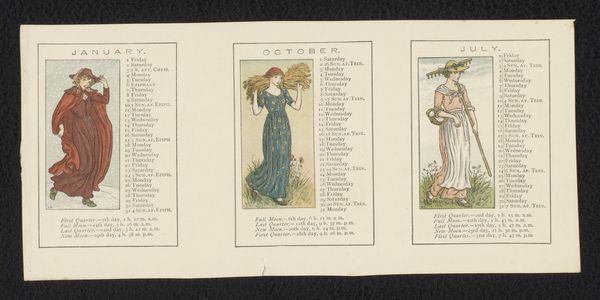

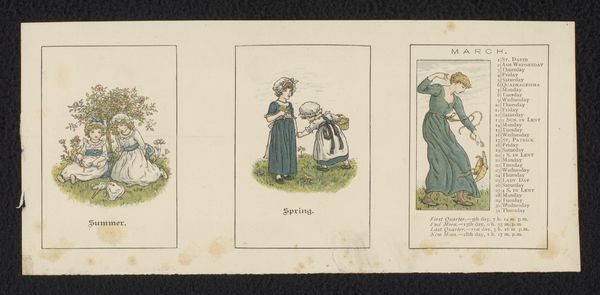

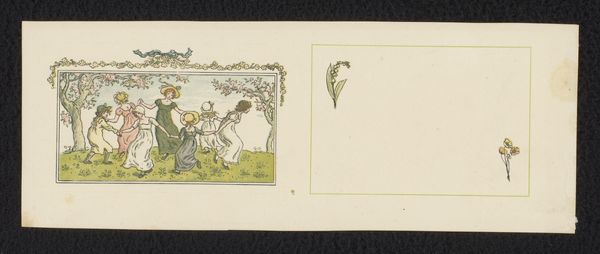

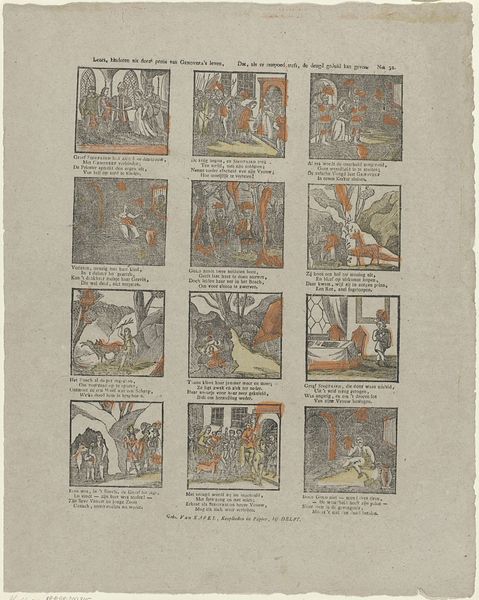

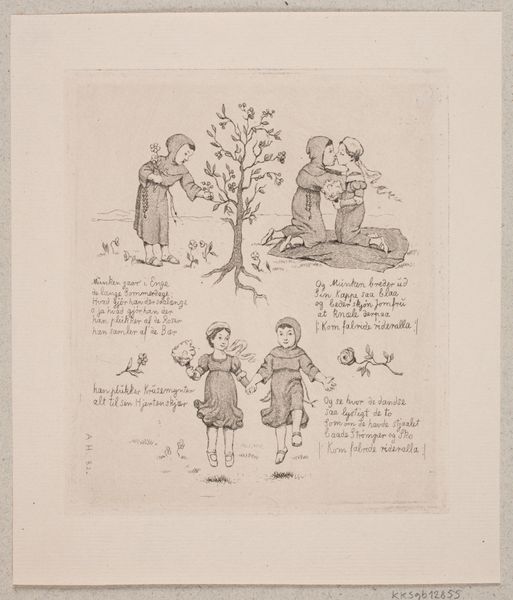

graphic-art, print

#

portrait

#

graphic-art

# print

#

landscape

#

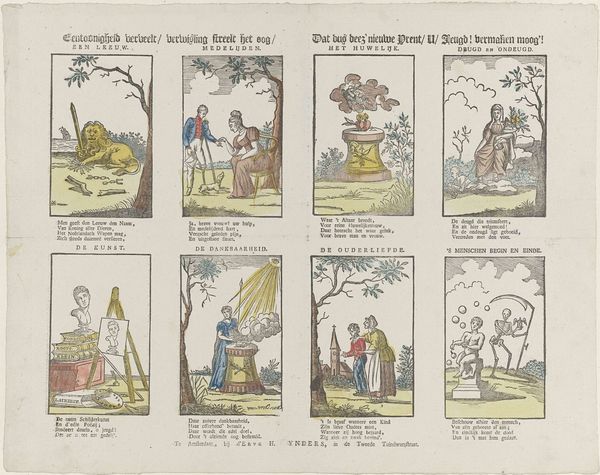

folk-art

#

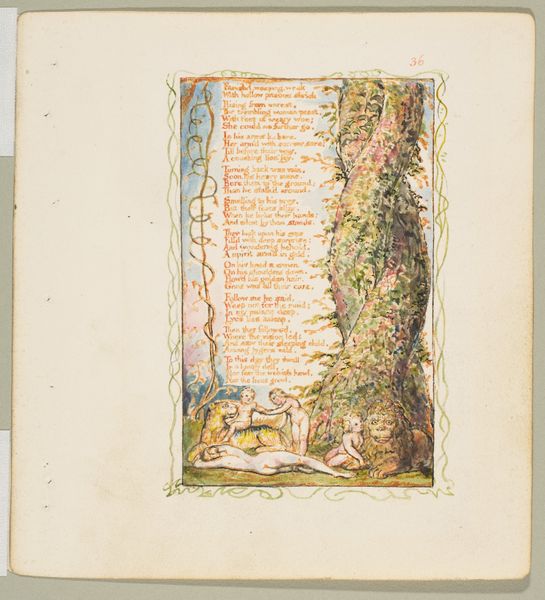

symbolism

#

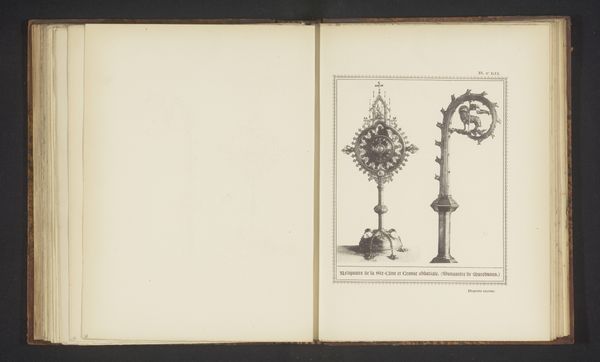

decorative-art

#

miniature

Dimensions: height 109 mm, width 238 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at these proofs, what first catches your eye? Editor: There's a delicate sweetness about them, isn’t there? A nostalgia baked into the pastel colors and these miniature scenes. They feel like fragments of a gentler world. Curator: Indeed. We’re viewing a print featuring six proofs for "Kate Greenaway's Almanack for 1892," attributed to Edmund Evans, who specialized in color wood-engraving. This sheet offers a fascinating glimpse into the creation of a popular illustrated almanac of the late 19th century. Editor: "Kate Greenaway’s Almanack," would've seen this as an emblem of idealized domesticity, and feminine virtues within a burgeoning industrial age? How was it circulated and consumed by the masses? Curator: Published annually, Greenaway’s Almanacks were immensely popular, functioning both as practical calendars and as showcases of her charming illustrations of children and seasonal imagery. These were often bound and given as gifts. Note the aesthetic details of folk-art traditions; consider how that design shaped cultural values of the time, particularly ideas about childhood and beauty. Editor: Right, the romanticization of innocence… and I can already hear the critics decrying its escapist sentiment. I’m drawn, however, to what it tries to preserve—a sense of connection to nature in the face of urbanization. And this care is further embellished and stylized in decorative motifs. Curator: The decorative borders and idealized figures speak to a yearning for a simpler, more picturesque past. This kind of design served not only as entertainment but also shaped and promoted a particular vision of British identity. Note, too, that Greenaway’s art was part of a broader Arts and Crafts movement that pushed back against the dehumanizing effects of mass production. Editor: You are right, and thinking of current trends in cultural products of beauty and decorum makes the impact more apparent, despite some anachronistic design quirks. As a matter of history, though, what makes this object remarkable to us now? Curator: Because the prints allow us insight into production processes of these mass distributed objects of beauty. The print displays proofs of each of Greenaway’s illustration works as printed, allowing us an intimate look at this historical moment in print-making practices. Editor: Seeing it as part of an industrial workflow, adds even another fascinating element. Now it feels far from simply 'sweet'—this object is complex with design and technique, and the era’s vision of innocence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.