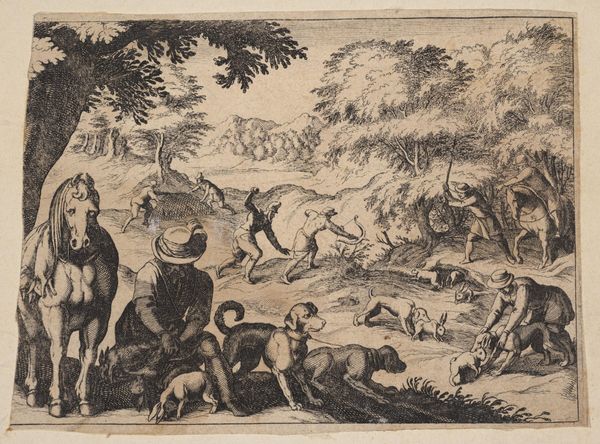

print, engraving

#

pen drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 318 mm, width 467 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately striking, isn't it? The level of detail in this black and white print is simply incredible! Editor: It does feel very busy, doesn’t it? All the flora and fauna vying for attention… Curator: Indeed. This is "Adam and Eve in Paradise," created by Pieter Serwouters in 1611. Currently it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you about it formally? Editor: Well, considering it is labelled a print, the intricacy of the line work and the texture he’s achieved are remarkable. It speaks to serious technical skill in engraving, don’t you think? So many details…fur, leaves, musculature. One wonders about the kind of tools he would have needed. Curator: Precisely. The piece really reflects its era. The Northern Renaissance was very interested in representing nature, and especially animals, in a lifelike fashion. This image is meant to convey both a literal biblical scene but also comment on then-current notions of paradise as an idyllic, natural place. Look at how nature frames their sin in this garden… a charged space, morally! Editor: Interesting point. And you've got Adam and Eve, not alone, but surrounded by all sorts of creatures – the natural world witnessing their fall. Also, given that it is an engraving made by Serwouters, presumably in multiples, who would have been the intended audience for a print like this? Wealthy individuals? Church institutions looking to communicate morality? Curator: Most likely a bourgeois or aristocratic clientele who wanted to own smaller, collectible depictions that reinforced certain social or political ideals. These images provided entertainment, promoted piety, and demonstrated a level of learning and refinement for their owners. It reflects much on how knowledge was disseminated during the time as well. Editor: Yes, it is indeed an object meant for private viewing but also for public display inside the household of the era. It invites speculation on how images and religious stories could have affected family dynamics, conversations, education. Looking at its production and distribution unveils that world. Curator: It certainly gives us much to consider regarding not only art history but also social history and materiality itself! Editor: I agree. By examining these artistic choices and social considerations, we gain a richer understanding of 17th-century ideas.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.