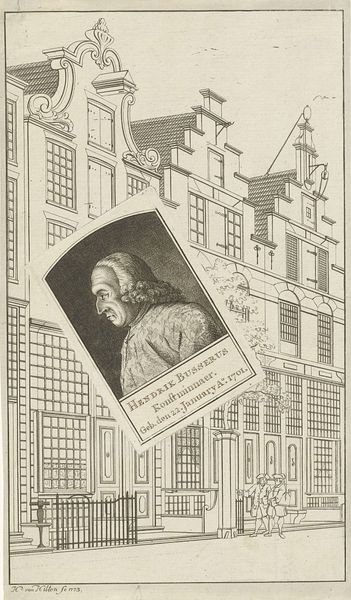

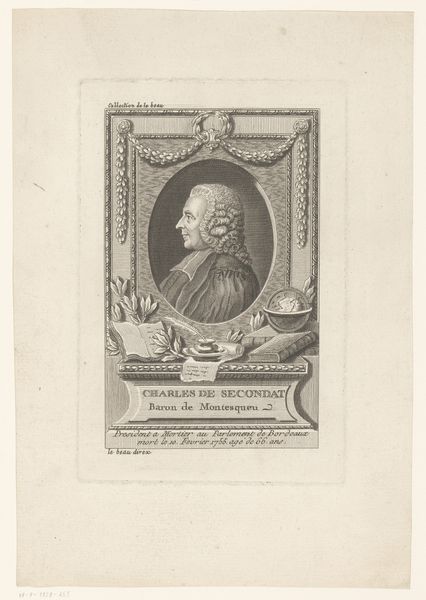

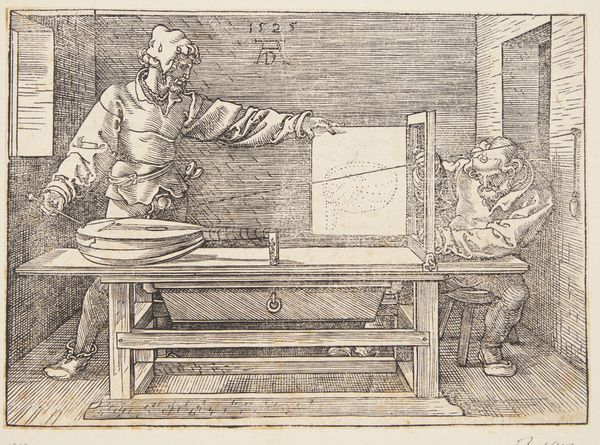

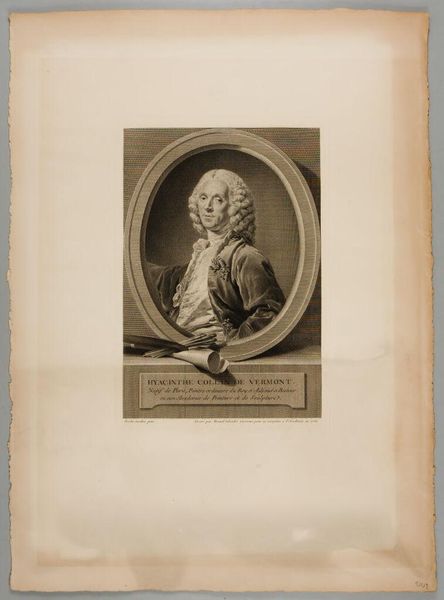

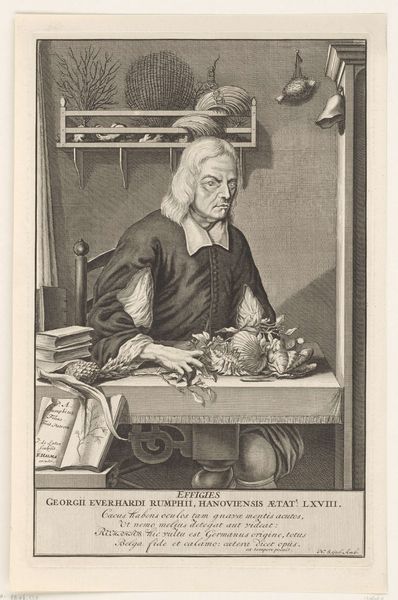

drawing, paper, engraving

#

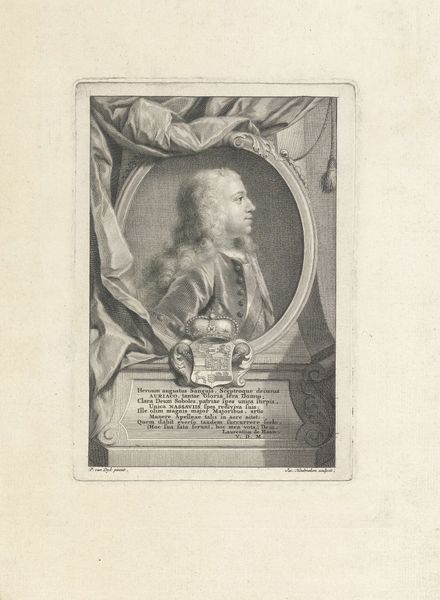

portrait

#

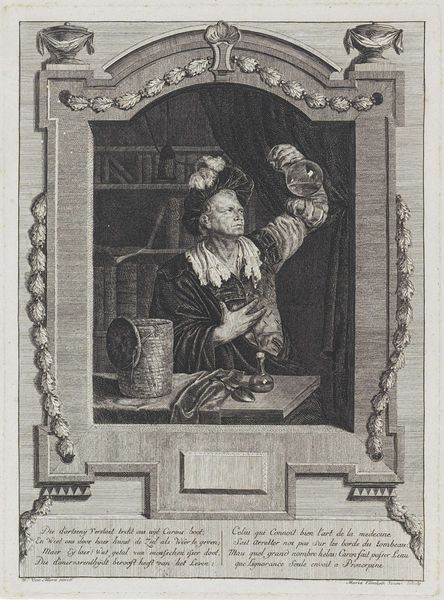

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

paper

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 129 mm, width 179 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving is entitled "Portret van Hendrik Busserus, omlijst met boekenkasten," made on paper by Julius Henricus Quinkhard between 1744 and 1776. Editor: It's a curiously domestic portrait; the bookcases dwarf the sitter. There's a calmness to the composition; muted, but inviting. Curator: Quinkhard worked in a highly structured academic style; portraits were commissions intended to express something about the sitter's identity, and that included material possessions. This drawing is clearly a commissioned piece. Notice the emphasis on literacy through its framing with books. This speaks volumes about social mobility and bourgeois values at the time. Editor: Absolutely. Books as a statement. And looking at the titles, "Atlas," "Theologici," "Botanici" - it reads as a catalogue of the man's knowledge and his self-professed identity as a scholar. It seems calculated to display intellect. Curator: Precisely. Engravings, unlike paintings, enabled wider distribution. Reproducibility meant ideas, fashions, and, yes, status could circulate. So it's about not just possessing knowledge but demonstrating it publicly to assert standing within Dutch society. This ties directly into mercantile activity; status becomes a tool. Editor: So, Hendrik Busserus used this technology as a soft of branding? An 18th-century Linkedin profile picture? Curator: In essence, yes. These engravings represent labour too. Think about the craftsman skilled in the techniques of Baroque and Academic styles of drawing that allowed this exact communication. How do their own identities appear here, suppressed behind the Busserus brand? The value isn’t merely in the final image. Editor: This brings up a much needed questioning. This portrait unveils how social capital worked then. And really asks: Who was profiting from this publicised access? Curator: Examining Hendrik Busserus's portrait through the lens of materiality helps us realize it served multiple purposes beyond a simple likeness. Editor: This pushes me to think more deeply about that age. Not just its art, but about its people and the labor that has survived into our material culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.