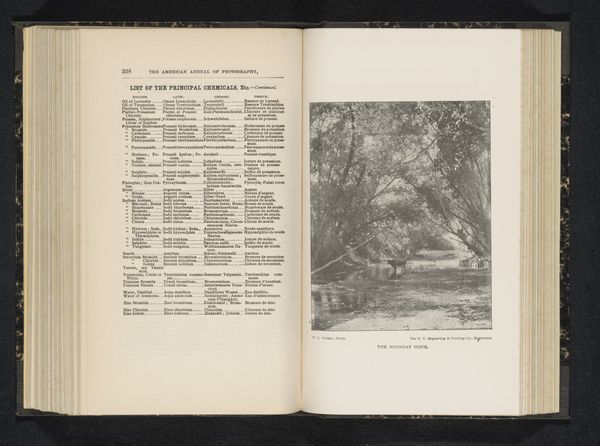

print, photography

# print

#

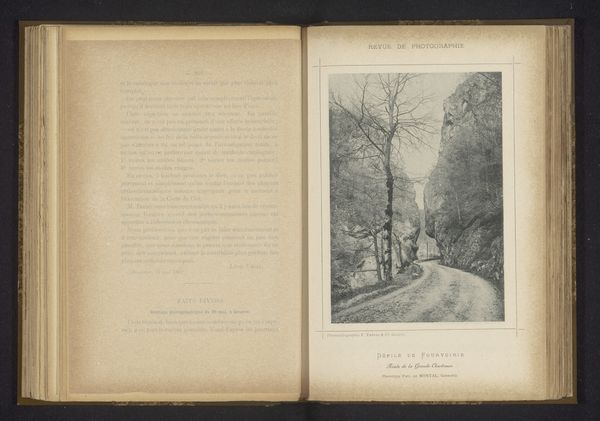

landscape

#

photography

#

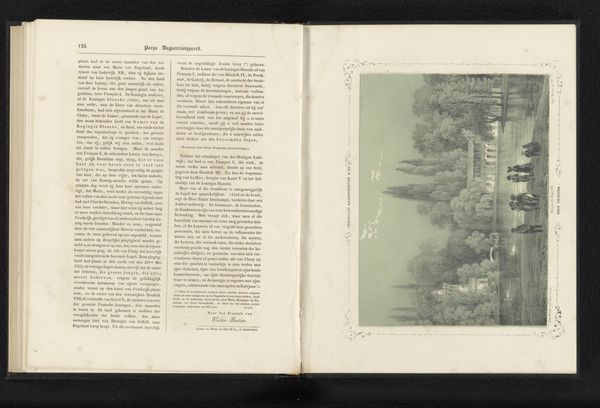

building

Dimensions: height 151 mm, width 107 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

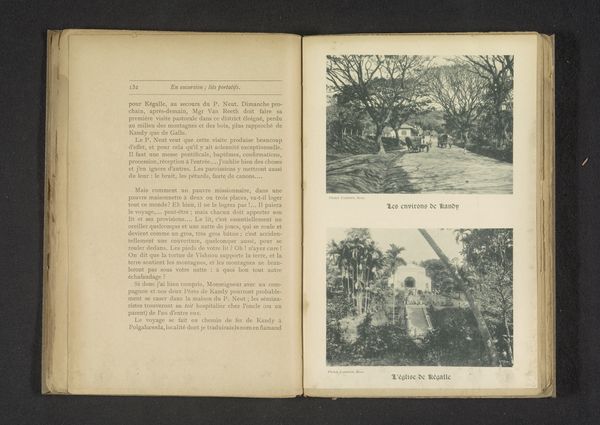

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this compelling print: “Exterieur van het Kreuzkloster te Braunschweig” by W. Berge, created in 1893. The image captures the exterior of the Kreuzkloster, or Holy Cross Monastery, in Braunschweig. What’s your first impression? Editor: There's a strong sense of solemnity here. The stark black and white, the bare trees—it creates an almost mournful mood. The long path draws the eye directly toward the building. Curator: Indeed. What interests me most is understanding Berge's process. This isn’t a straightforward photograph, it's a print. What kind of labour was required to translate this scene? How were photographic technologies and printmaking techniques intertwined at the time, and what does this reveal about the hierarchies between art forms? Was this considered art, documentation, or something in between? Editor: I'm drawn to how this scene represents a specific kind of power structure through its architectural forms and setting. The monastery's stone façade, viewed through leafless trees, might imply the rigidity of religious and class structures—as perhaps felt during this moment in the late 19th century. Is this just a beautiful landscape, or is it about institutions and access? Who had access to places like this then, and who has it now? Curator: Precisely. We have to remember that prints were often produced for wider consumption. So who was the intended audience? Were these images tools for education, civic pride, or simple mementos for the burgeoning middle class? These reproductive technologies changed who got to experience this location—not only on paper but physically, too, since the images boosted tourism. Editor: Considering Braunschweig's history as a city wrestling with shifting political dynamics, and a history of shifting identities, perhaps this image is hinting at anxieties linked to changes of power or old authority. The photograph shows a structure from a period when these monasteries yielded to secular governments, making such places more relevant, as buildings, than for religious purposes. The landscape's silence speaks to this societal shift, I feel. Curator: Yes. And the choices in printmaking speak to shifting artistic value. It makes you wonder how something we might pass off today was deeply rooted in the social fabric. Editor: It's definitely a work that reminds us of how every visual choice is intertwined with narratives of social and historical change. Curator: A worthy lens through which to consider even what looks like a simple scene.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.