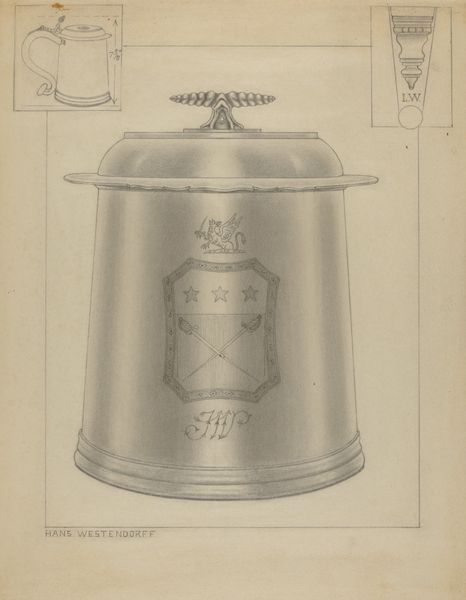

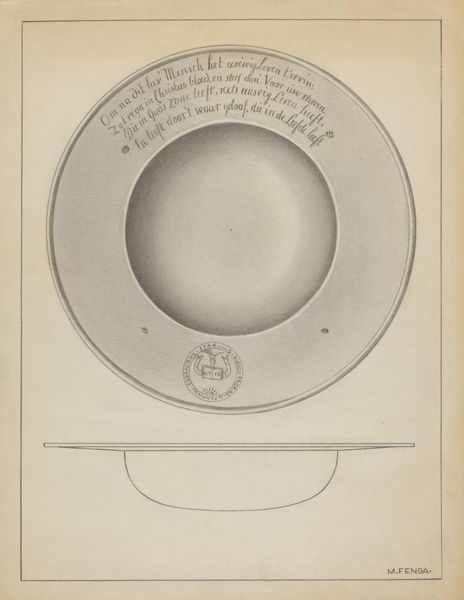

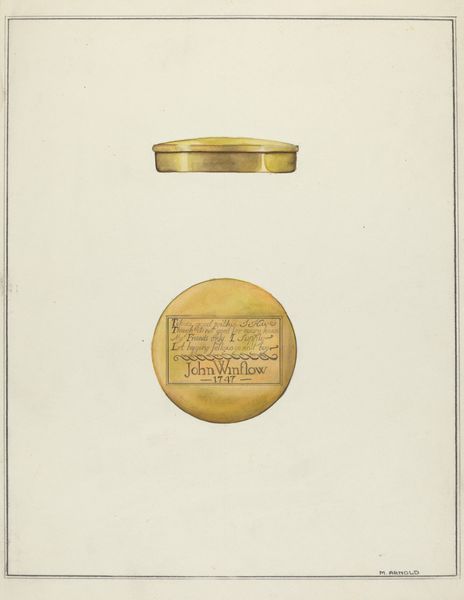

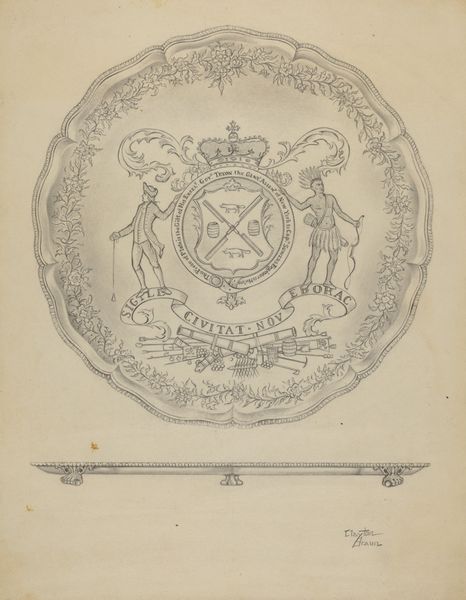

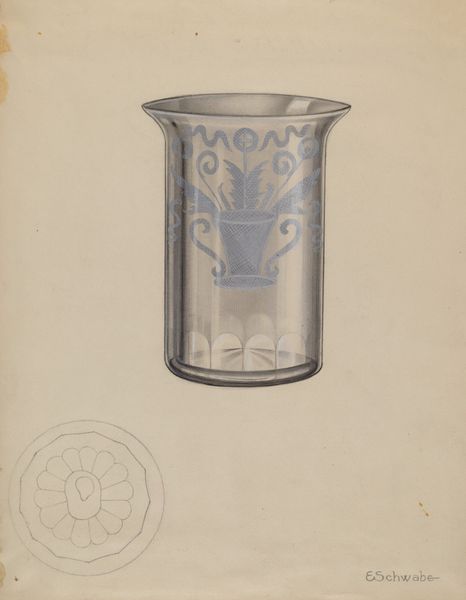

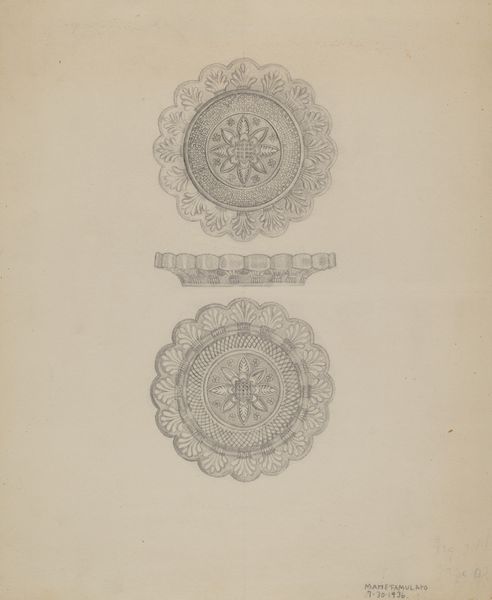

drawing, ink, pencil

#

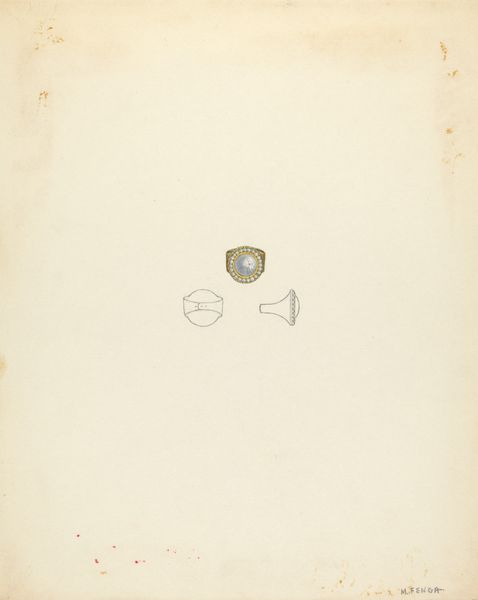

drawing

#

ink

#

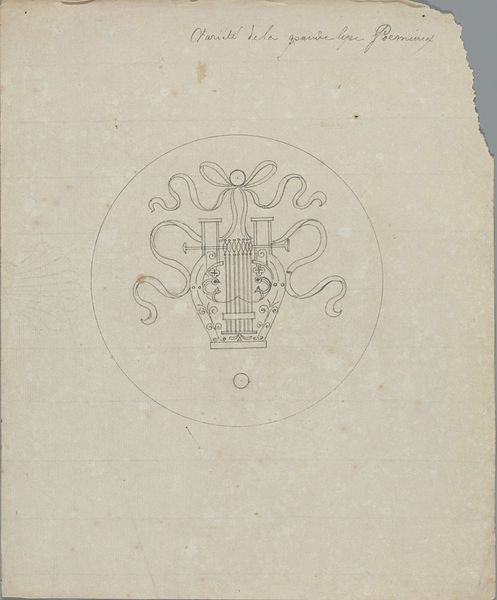

pencil

#

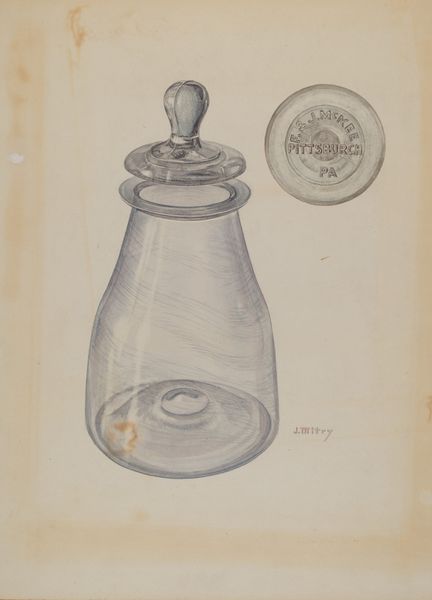

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 29.1 x 22.5 cm (11 7/16 x 8 7/8 in.) Original IAD Object: 14 1/2" High 7 1/2" Dia.(top) 7 1/4" Dia.(base)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at Frank Fumagalli’s drawing, "Churn," likely created around 1936, we see a meticulously rendered image primarily using pencil and ink, though there's a suggestive use of watercolor around the form, and this choice certainly prompts observation. What are your initial thoughts on this seemingly humble piece? Editor: My first impression is one of starkness and almost a muted industrial quality despite its rather mundane subject matter. The sparse lines give it a feeling of precision, while the very muted colors give a sense of vintage utilitarian design. What do we know about its production, materials and, more broadly, what do you think it reflects about its context? Curator: Fumagalli, about whom little is known beyond his illustrations and work with the Index of American Design, captured not just an object, but an aspect of early 20th-century Americana during a time when national identity was being redefined through various art projects, which might illuminate how social structures and aesthetic preferences evolved in pre-war America. The churn’s design points towards a society that values a fusion of functionality and understated beauty. It reflects an intersection where practicality and an emerging sense of 'American' aesthetics met. Editor: Precisely, and by paying attention to the craftsmanship – how the lines capture not just shape, but the implied volume and texture – we see value placed on process, and an aesthetic derived from production. I’m particularly drawn to how the materiality, suggested by ink and watercolor washes, is integral to how it conveys the object’s potential use, linking labor and design through visual language. Curator: It's as if Fumagalli intended for the image to be an accessible piece for everyone in its period and beyond. It makes me wonder, though, how viewers at the time received a work so divorced from high art. Did they see in it something revolutionary, something that questioned their prevailing assumptions, or simply a tool made appealing? Editor: Possibly both. The appeal isn't just visual; it's textural, suggestive, like a recipe handed down – connecting the making of art to the making of everyday life, while the technique makes what might have been thought of as applied design as important as more formally composed "fine" art, bridging social gaps through art appreciation and a more hands-on attitude. Curator: The politics inherent in imagery here seem to revolve around the normalization and almost heroic elevation of utilitarian design and everyday existence within an American narrative. A single object that reflects the many facets of material culture and daily lives that built a nation. Editor: Absolutely, by embracing these 'mundane' items in fine rendering, artists acknowledged and perhaps valorized, processes that defined social strata through production and consumption. Food production and manufacturing. I walk away sensing its inherent quiet celebration of the handmade that is on its way to the machine-made, which could give the work new appreciation across our time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.