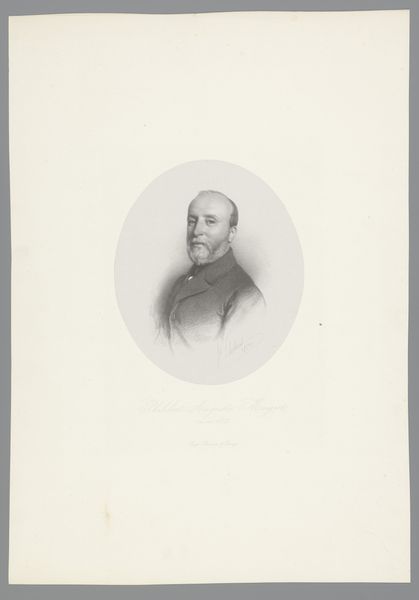

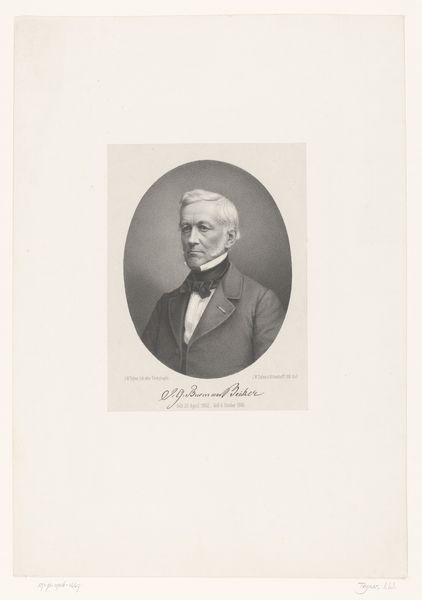

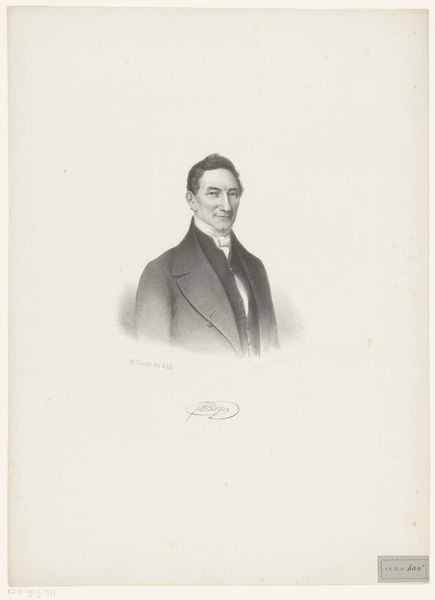

Portret van Aymard-Charles-Marie-Théodore markies de Nicolaÿ 1847 - 1885

0:00

0:00

josephschubert

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 488 mm, width 340 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There's an immediate serenity about this portrait. Editor: Indeed. We are looking at a pencil drawing from sometime between 1847 and 1885, now held here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s entitled "Portret van Aymard-Charles-Marie-Théodore markies de Nicolaïff", and its creator is Joseph Schubert. It's a wonderfully poised example of the academic style in portraiture. Curator: His gaze… there’s a detachment there. It feels less about connecting with the viewer and more about presenting a specific image, almost a stoic acceptance of duty. Editor: Precisely. Portraits of this era served a very clear societal function. They were commissioned by individuals like the Marquis to solidify their place, not only in their immediate circle but also for posterity. Notice the precise rendering of his features, the controlled shading creating a dignified persona. Curator: That stiff cravat also contributes to this aura of formality and restricted self-expression. It feels symbolic of the constraints of aristocratic life. Editor: Absolutely. The rise of Romanticism also influenced portraiture. It was intended to portray a sense of order. However, this era embraced realism in art, so there was still a commitment to capturing the subject as closely as possible to their likeness and features, as the aristocrat class of that era aged. The artist here, Schubert, expertly toes that line. Curator: But I also notice the subtleties— the gentle curve of the lip, the soft light catching his hair. Schubert managed to breathe a spark of individuality into this man beyond the markers of nobility. Do you notice those glints of gentle light? Editor: That observation reminds me of how such commissions walked a fine line between idealization and factual depiction. Too much idealization might be viewed as vanity or as a political misstep, whereas something hyperrealistic could cause one to appear aging and weak. So, we circle back around to control. Curator: A balance carefully maintained by both the sitter and the artist, then. It makes me wonder about the power dynamics at play and who really was crafting the visual narrative. I feel that portraits of this type act like icons, less concerned with individuality than representation of an archetypal symbol. Editor: And the Marquis certainly wanted to ensure that message of unwavering dignity would endure long after he departed from this earth. It’s an incredibly well-executed exercise in the public construction of legacy and self, though. Curator: A silent but compelling performance then. Editor: Exactly, a portrait to remember.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.