drawing, print, ink, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

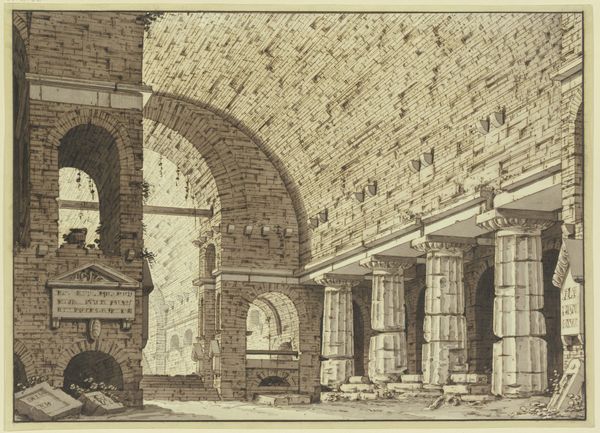

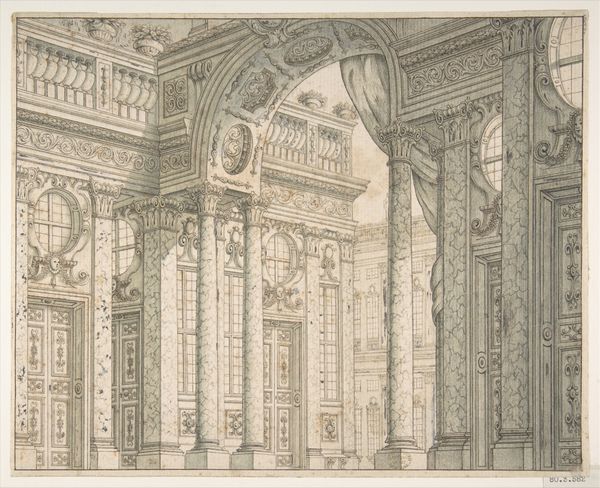

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed): 11 11/16 × 17 1/16 in. (29.7 × 43.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The pen and ink drawing before us is titled “A Grotto,” and it's attributed to Antonio Fantuzzi, dating to around 1540-1560. Currently, it resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It has a rather haunting quality, doesn't it? The density of line work creates a cavernous depth, yet also traps the eye. I am immediately drawn in but don’t feel welcome to explore too deeply, particularly as every column seems to sprout demonic faces. Curator: Indeed. Grottos during the Italian Renaissance were artificial caves, often incorporated into gardens. They were places of retreat and display, intended to evoke a sense of classical antiquity and the sublime power of nature, particularly of Ovid's Metamorphoses. Wealthy landowners displayed art, sculpture and plants within. Editor: And in this case, Fantuzzi represents the sublime through almost suffocating detail. Look at the arches themselves. They frame an interior, but the rough stonework fights the geometry—an unsettling combination of naturalism and classical form. And that sense of entrapment increases further down the colonnades. Curator: I agree. There is a push and pull. Renaissance grottos became theatres of power and were built by figures looking to cement their legacy. Fantuzzi was connected to the school of Fontainebleau at this time. Given the architectural emphasis in Fantuzzi's work, I wonder whether he made preparatory drawings for court festivals. Editor: The artist really maximizes the sense of depth by reducing the amount of tonal contrast and increasing line density in the further recesses. The perspective is not quite perfect. It seems deliberately skewed, heightening the disorienting effect. I want to be drawn further in but hesitate because the artist has flattened all three dimensions. Curator: Exactly. As viewers in the 21st century, we come to this image with layers of assumptions, forgetting perhaps that in the 16th century such architectural follies represented both the ambition and perhaps hubris of power. They transformed the environment at the expense of labour and resources. Editor: Seeing how you've helped to contextualize this grotto’s architectural space allows me to notice nuances in the structure. What had struck me simply as ominous detailing might signify something quite specific about Italian power and landscape appropriation. Curator: Absolutely. Fantuzzi's "Grotto" becomes a commentary on the era’s aesthetic and social values rather than just a drawing. Editor: Yes, by bringing into context this piece, I appreciate now, how form becomes informed by social issues. Thanks to you, I feel empowered and comfortable moving forward with the next stop.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.