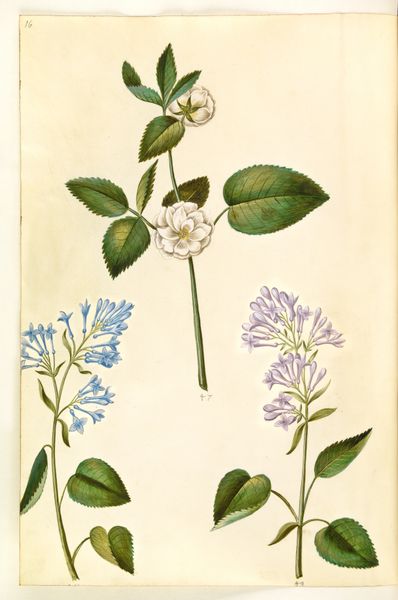

Phaseolus coccineus (pral-bønne); Cerinthe major (stor voksurt); Borago officinalis (almindelig hjulkrone) 1635 - 1664

0:00

0:00

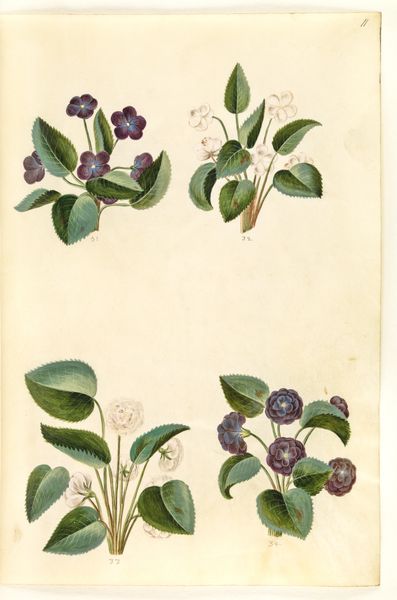

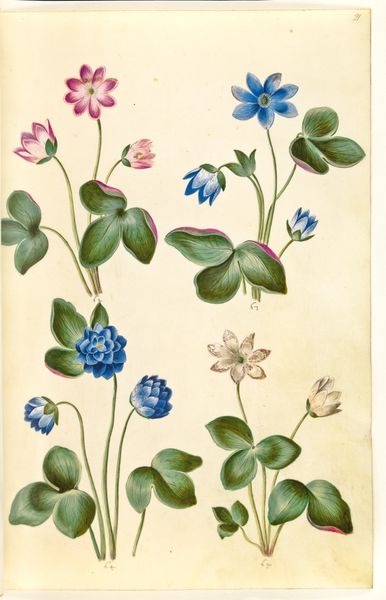

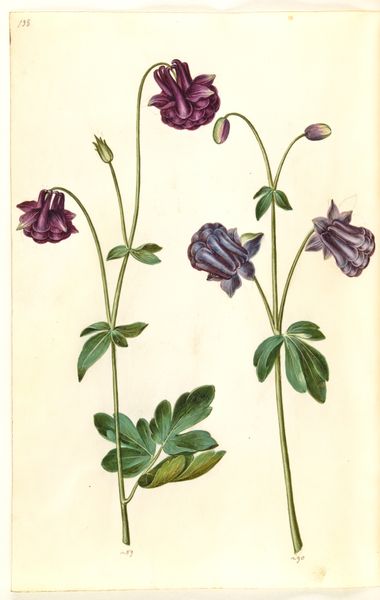

drawing, gouache, watercolor

#

drawing

#

still-life-photography

#

gouache

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

botanical art

Dimensions: 375 mm (height) x 265 mm (width) x 85 mm (depth) (monteringsmaal), 358 mm (height) x 250 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: What a captivating study in naturalism! We're looking at a botanical drawing from between 1635 and 1664 by Hans Simon Holtzbecker, titled "Phaseolus coccineus (pral-bønne); Cerinthe major (stor voksurt); Borago officinalis (almindelig hjulkrone)". Holtzbecker masterfully employed watercolor and gouache on paper. Editor: The composition strikes me immediately. It feels meticulously observed yet almost ethereal, given the washes of color. The detail in the leaves is particularly remarkable. Curator: Agreed. Let's consider Holtzbecker's approach. As a court painter, botanical studies weren't simply about aesthetics. They served a practical purpose, perhaps informing medicinal or horticultural practices. How the pigments were sourced, how he ground them, all influenced the availability and longevity of the art, which, as raw materials, often came from far away. Editor: And from an iconographic perspective, flowers and plants in this era often carried symbolic meanings. The Borago officinalis, or borage, with its vibrant blue flowers, for example, has long been associated with courage. Its presence here perhaps alludes to bravery and resilience. Curator: Good point. This resonates when considering the context. Europe was transforming, societies reorganizing to supply newly developed desires in both home and industry, from textiles to spices. Holtzbecker isn't just showing us pretty flowers, but the literal and conceptual material used to create and feed European society and visual culture. Editor: There is a palpable tension. Holtzbecker documents an early empirical investigation into a natural phenomenon with precision, but the medium softens the hard-edged "scientific" view with inherent artifice. Curator: That interplay is vital. It highlights the active labor needed to procure these "natural" elements and transfer them from the natural, unprocessed environment, to a controlled, highly coded one like this painting. The hand of the artist is visible in both respects. Editor: Absolutely. The way Holtzbecker captures the veins on the leaves, for instance – they are like maps, charting not just the plant’s anatomy, but our understanding of the natural world at that time. There is an unmistakable humbleness that lies between observed object, and human effort. Curator: The symbolic interpretation is grounded in the understanding of labor, in material extraction, processing, and social coding to which plants became subjected. It creates an intellectual tension—knowledge in the service of resource, versus the artistic impulse to reveal truth. Editor: Well said. It's a work that reveals the layered meanings we bestow upon the natural world and the visual symbols by which those meanings become transmitted. Curator: And in his expert rendering, Holtzbecker shows not only nature’s splendor but humanity's profound ability to transform and be transformed in kind by nature.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.