photography, albumen-print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 182 mm, width 241 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

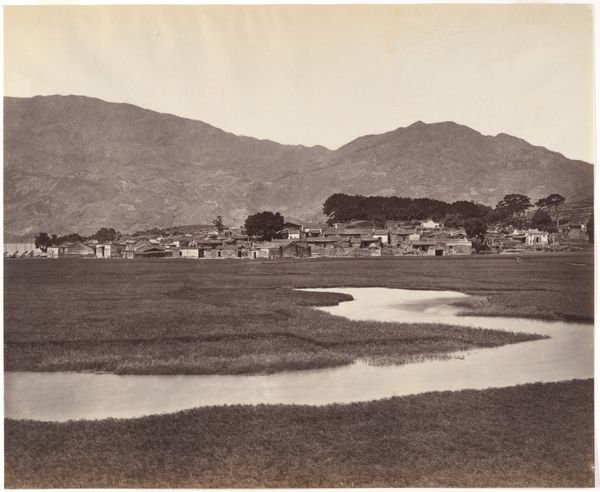

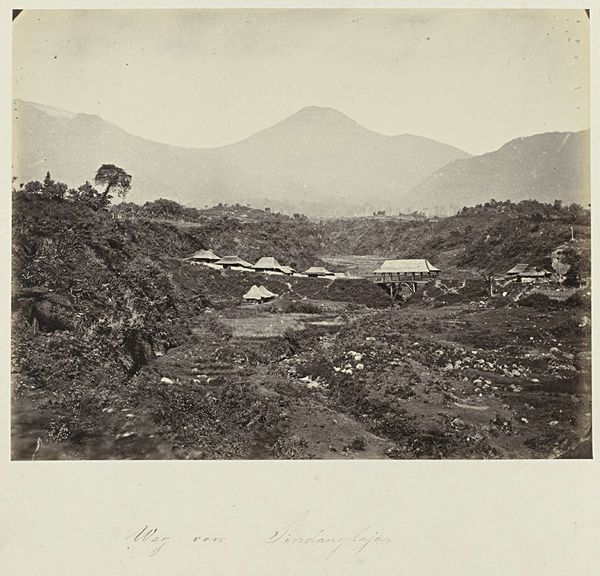

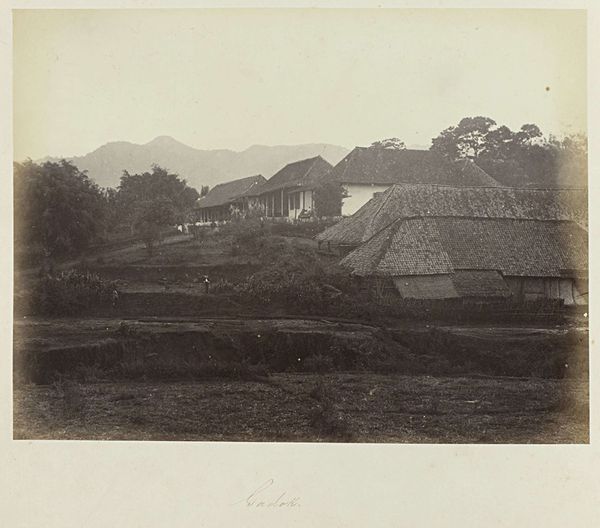

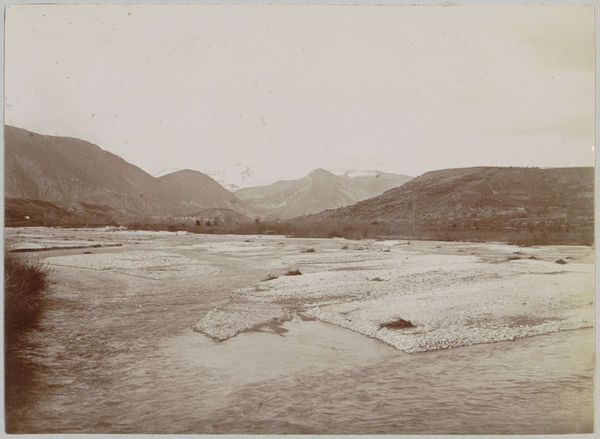

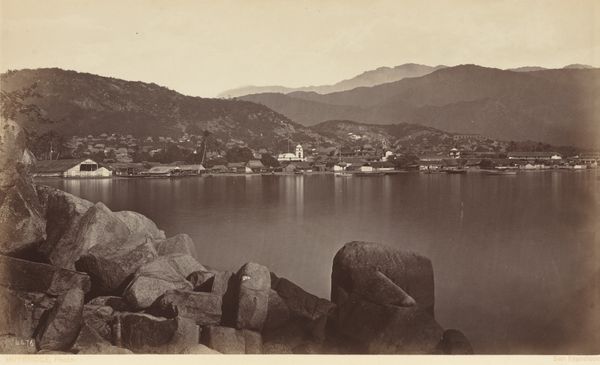

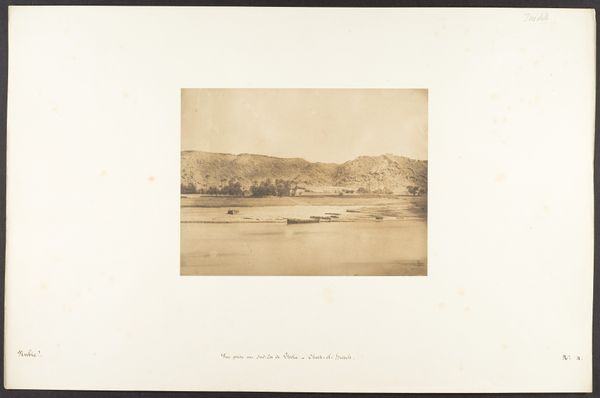

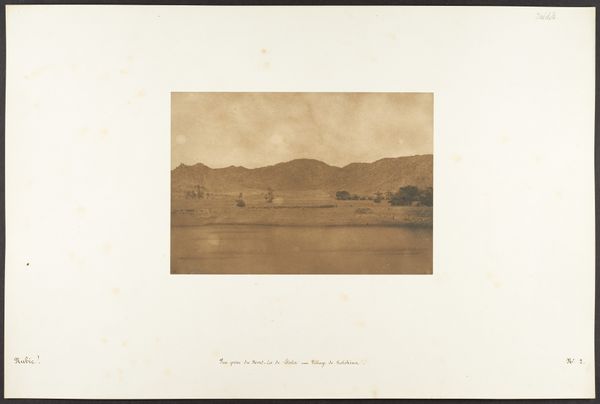

Curator: "Meer bij Sindanglaja," or "Lake at Sindanglaja," an albumen print made sometime between 1863 and 1869 by the firm of Woodbury & Page. It's quite striking. Editor: Yes, a serene and balanced composition. The reflection in the water mirrors the mountains beautifully. A feeling of quiet grandeur. Curator: I find it fascinating considering the context of its production. This is colonial Indonesia. Woodbury & Page were a commercial photography studio catering to a European clientele. They captured images of the landscape, architecture, and people, turning them into commodities. This seemingly picturesque view is implicated in a system of power and control. Editor: I agree, yet there's still something powerful in the image itself, irrespective of its colonial undertones. Water often symbolizes reflection, subconscious thoughts, even cleansing. Paired with the mountains which can represent permanence or challenges, it forms a symbolic narrative. Is this photographer seeking some solace amidst colonial enterprise, maybe even asking for change? Curator: Or perhaps just seeking profit. These prints were mass-produced. Labor was cheap, and the materials readily available. The albumen process itself, using egg whites, involved a very specific type of work. I can't divorce myself from those realities when looking at this. The labor that went into its production shapes its meaning as much as, or perhaps even more than, its symbolic weight. It is about the materials, how they come together. Editor: I appreciate your point, the tangible realities are indeed integral. At the same time, even commercial images become historical artifacts in their own right, often resonating in unpredictable ways. One element I note are the native buildings pictured among a colonial presence; are we meant to compare how people dwell on the land and its possibilities? Curator: Interesting. You bring up the question of intent; the colonial gaze is never really transparent, and perhaps its lasting visual record holds meaning not originally anticipated by the producers. Editor: Indeed, and maybe our diverse views towards interpreting it is one good use to the visual culture these companies manufactured. Curator: I agree that bringing modern attention to the context and material involved expands our perception of not only the artwork but those historical eras as well. Editor: And how lasting memories emerge as a constant conversation with the symbols that linger on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.