Dimensions: Image: 32 x 43 cm (12 5/8 x 16 15/16 in.) Mount: 46 x 60.5 cm (18 1/8 x 23 13/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

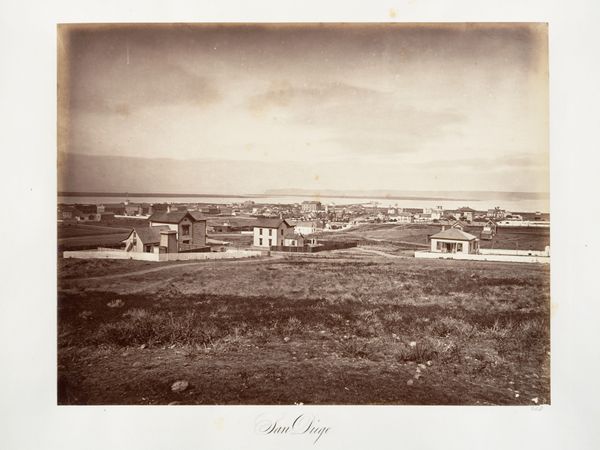

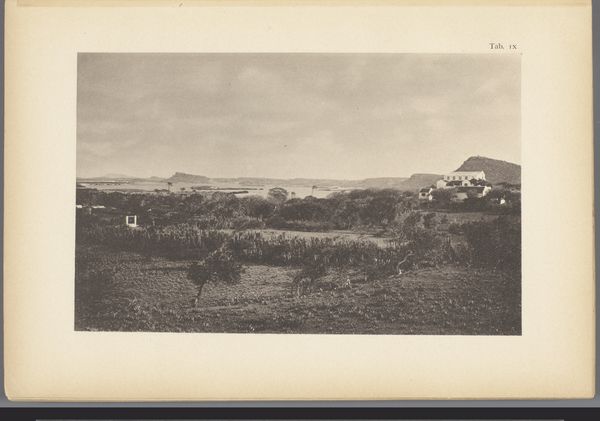

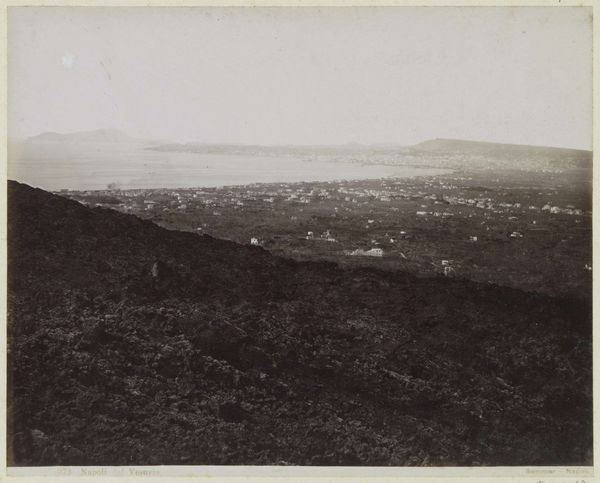

Curator: This is Edouard Baldus’s “St. Nazaire,” a captivating albumen print made between 1859 and 1862. It gives us a sweeping view of the coastal town. The print itself is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: There's something incredibly still about this image. The composition, with that rough, earthy foreground sloping down to meet the tranquil bay, creates this sense of a quiet observation, a town suspended in time. It’s muted and monochromatic palette conveys almost an melancholic ambiance. Curator: Absolutely. The albumen print process Baldus used, treating the paper with egg white before coating it with silver nitrate, gives it that subtle tonal range. It allows for capturing the details in both the shadowed foreground and the brighter distance of the buildings along the shore, but also demanded lengthy exposure times, so that stillness you perceived is quite literal. Consider Baldus’s broader career. His commissions to document architectural landmarks were acts of preserving and documenting not just buildings but social structures undergoing rapid change at the time. Editor: Precisely! And that is especially pertinent in St. Nazaire. The town, depicted in a seeming pastoral state, actually carried the deep scars of political repression, specifically the 1848 June Days Uprising in France. It served as one of France's primary penal colonies. What does it mean to see a location like that, which for many signifies loss and hardship, photographed with such...equanimity? What narrative is deliberately silenced, and how does Baldus' position as a photographer in that historical moment influence the aestheticization of what's literally and metaphorically in the picture? Curator: Those kinds of tensions— between objective record and artistic license, between representation and exploitation—are critical to analyzing the political weight of photographs, but also remind us that we bring contemporary values and theoretical frameworks to works created in very different material and ideological contexts. How do we balance an evaluation of process and the socioeconomic implications of that process, versus imposing meanings retrospectively onto Baldus? The production constraints themselves impacted both the aesthetic outcomes, as we’ve observed. The costs, the technologies of photographic equipment available, even the physical constraints on the scale of the print and how those prints would be assembled and consumed–all shape the context we examine and respond to when viewing works like "St. Nazaire" today. Editor: Ultimately, thinking about images like this means continually re-evaluating what we think we know about art, about history, and about each other. Baldus offers both something and suppresses many facets. Curator: Yes. Engaging with historical images can both sharpen and challenge contemporary awareness of social dynamics and aesthetic judgements and processes in artistic output and meaning making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.