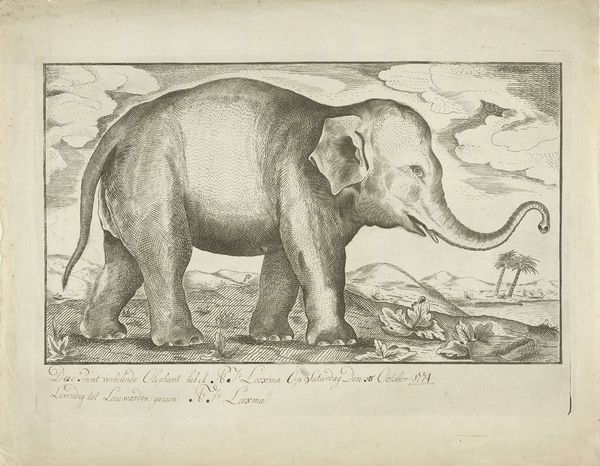

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 10.9 x 13.3 cm (4 5/16 x 5 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

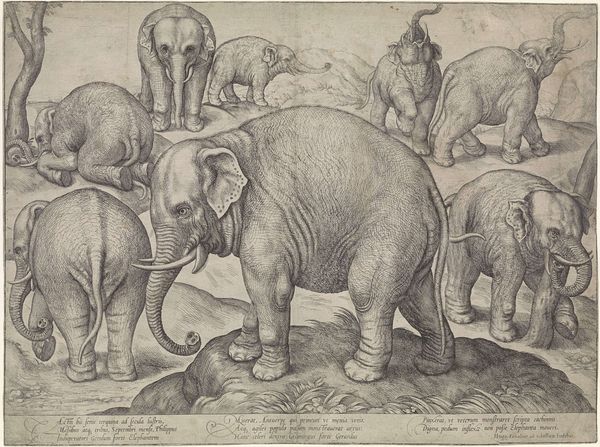

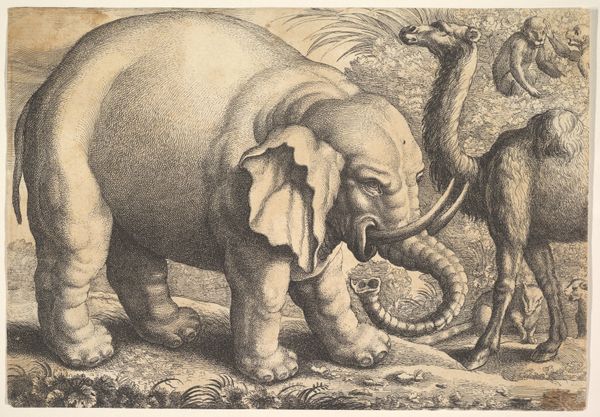

Curator: Before us, we have Martin Schongauer's "Elephant," an engraving likely created between 1480 and 1490. Editor: It's strangely captivating. There's a beautiful awkwardness to it, and the line work is so detailed and controlled, yet the proportions feel… off. Curator: Indeed. The image reflects the era’s understanding—or rather, misunderstanding—of exotic animals. Elephants were incredibly rare in Europe at the time, largely known through descriptions and not direct observation. Editor: So, it's less a portrait and more a cultural projection? I mean, look at the tower on its back! That speaks volumes about how they envisioned the animal being used—a beast of burden, a mobile fortress, a symbol of power, rather than a living being. Curator: Precisely. And consider the historical context. This print circulated widely. Schongauer's "Elephant" becomes a vehicle for disseminating not just an image, but also an ideology about human dominion over the natural world. It's a form of early colonial imagination. Editor: That's where it gets unsettling. We see the fine detail in the rendering, almost like a scientific illustration, but it’s promoting a narrative of control and exoticism that erases the animal's agency. The craftsmanship is superb, but it serves to reinforce existing power structures. Look at the tiny rider; barely registers! Curator: But it also introduced audiences to the wider world. The circulation of such prints undoubtedly played a part in sparking curiosity in foreign lands. And that detail and the controlled line you described so well was the result of Schongauer being a goldsmith before he took to engraving. Editor: Yes, it opened new avenues, while at the same time imposing a European framework. I think that contrast is exactly where the image speaks most loudly. It invites us to consider our responsibility in representing others. Curator: And also demonstrates how culturally charged an artwork can become beyond the artists original intention. It also acts as an historical reminder. Editor: Exactly. Seeing the "Elephant" through this lens allows us to discuss how such portrayals continue to inform perceptions of marginalized communities today. Curator: It's a beautiful print to have initiated that discussion. Editor: I agree. A truly rich object to contemplate, both for what it shows, and what it conceals.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.