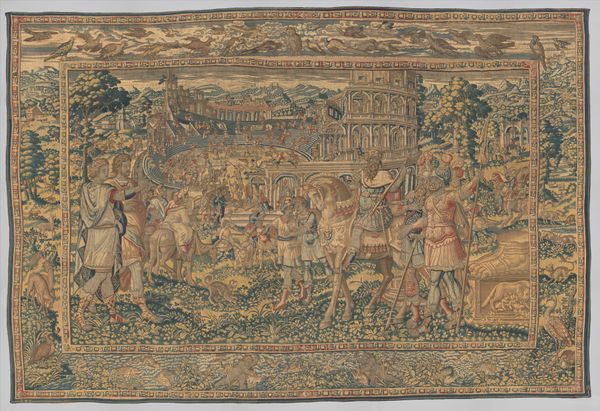

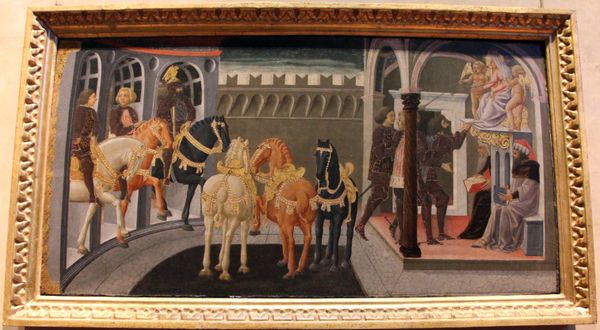

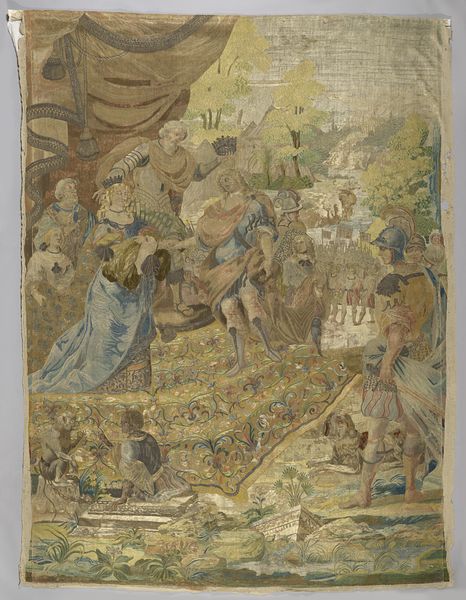

King Brennus of Gaul Captures the City of Rome; Marcus Furius Camillus Expels King Brennus From rome 1450

0:00

0:00

tempera, painting

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

early-renaissance

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: Here we have Lo Scheggia’s “King Brennus of Gaul Captures the City of Rome; Marcus Furius Camillus Expels King Brennus From Rome,” a tempera painting dating back to 1450. It's quite the busy scene. What stands out to you when you look at this piece? Curator: Well, immediately I think of the politics of imagery and historical narratives, and who commissions them. Given the Early Renaissance style, likely someone from the rising merchant class wanting to associate themselves with Roman virtues. Look at how the artist crams the canvas; it speaks volumes about how this story was valued and visualized. It’s not just art, it's propaganda. What do you think that narrative is doing here? Editor: You think it's about wealth, Roman virtues and showing the patron in a certain light. It seems pretty clear from the title what story is important here – the Romans bravely rising against invasion – but does that reflect reality? Curator: History painting in this period, like much art, was used to legitimize authority and create national myths. How accurate is this representation of events? It's really about instilling civic pride, linking patrons to this ideal. Brennus, the Gaulish leader, is diminished here. It promotes ideas about Roman greatness and the protection of the city. It creates, or bolsters, a national identity. Editor: So it’s not just about historical record, it's a lesson or maybe even encouragement. Curator: Precisely. This piece says, ‘We are the heirs to Roman resilience; we too can overcome.’ Art becomes a tool of governance. These kinds of narratives about triumph against all odds would really resonate during periods of conflict. But who really benefitted from the promotion of those sentiments, you think? Editor: Now, understanding the painting’s role as a social and political statement, rather than just a historical depiction, changes my perspective completely. I was originally focusing on the visual spectacle of the piece, but seeing it as a tool to construct a particular narrative is eye-opening. Curator: Absolutely, thinking about this type of work helps one consider visual narratives in a broader framework – how power influences what stories are told and remembered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.