metal, sculpture

#

portrait

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

11_renaissance

#

sculpture

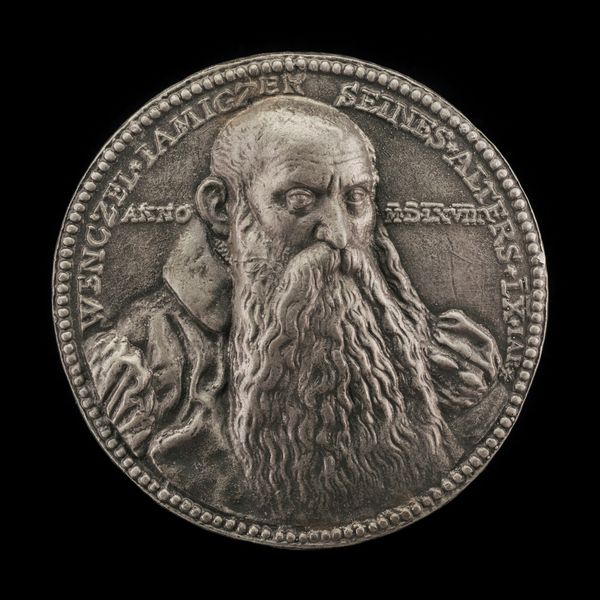

Dimensions: overall (diameter): 5.59 cm (2 3/16 in.) gross weight: 24.01 gr (0.053 lb.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Here we have "Jobst Tetzel, 1503-1575, Patrician of Nuremberg," a metal sculpture by Valentin Maler, dating back to 1569. It’s striking how such intricate detail could be achieved on a small, circular surface. What stands out to you about this piece? Curator: This medallion speaks volumes about the socio-political dynamics of the Renaissance. Medallions like these were powerful tools of self-representation for the elite. Jobst Tetzel, as a patrician of Nuremberg, was keen to project an image of gravitas and wisdom. How do you think the choice of metal as a medium plays into this self-presentation? Editor: It adds to the sense of permanence, doesn't it? Like solidifying his legacy, quite literally. So, beyond personal legacy, what role did pieces like this play in the broader cultural landscape? Curator: They were instruments of power. By commissioning such a portrait, Tetzel controlled his image. These medallions were often distributed, acting almost like early forms of political or social propaganda. The very act of crafting and circulating this image reinforces his status and influences how he's remembered. Editor: So, it's less about artistry for art's sake and more about strategically crafting an image? Curator: Precisely. It makes you consider the artist’s role, doesn't it? Was Maler simply fulfilling a commission, or was he consciously participating in constructing Tetzel’s public persona? It’s also interesting to think about how this piece would have been displayed or used. Was it a personal keepsake or a public symbol? Editor: That really shifts my perspective. It’s not just a portrait; it's a carefully constructed narrative for public consumption. I’ll definitely look at portraiture differently now, considering the power dynamics at play. Curator: Indeed. Art often serves purposes far beyond the purely aesthetic, especially in the Renaissance. This piece reminds us to critically examine the intended audience and the social forces that shaped its creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.