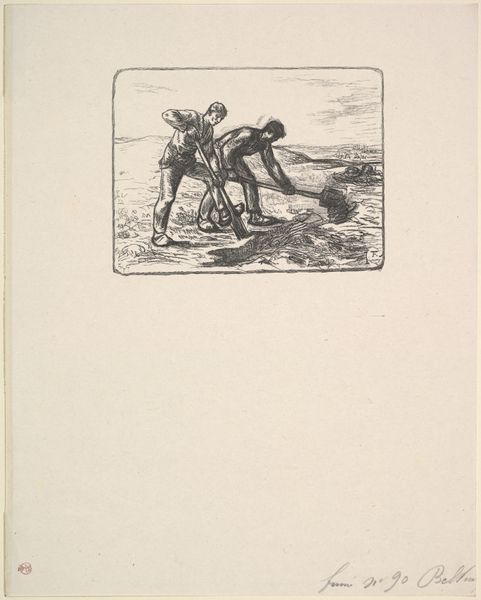

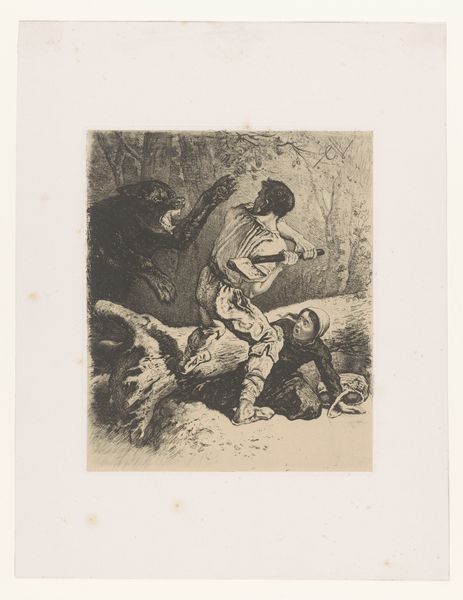

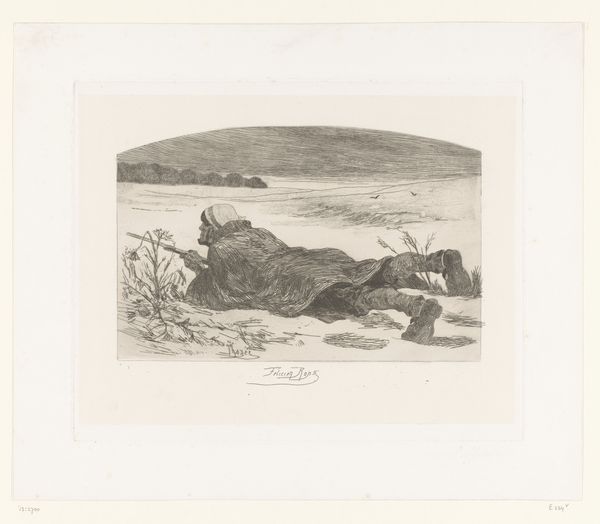

The Ass and Two Thieves, plate 75 from Souvenirs d’artistes 1862

0:00

0:00

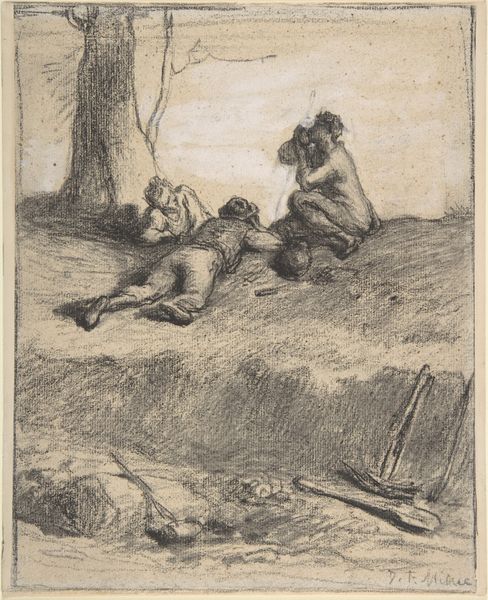

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

caricature

#

paper

#

realism

Dimensions: 229 × 203 mm (image); 450 × 316 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: We're standing before "The Ass and Two Thieves," plate 75 from *Souvenirs d’artistes*, a lithograph by Honoré Daumier, created in 1862. It’s part of the collection here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately, I see this struggle—brutal and raw. There's a theatricality, yet it also feels intimately real, like a street scene witnessed from a window. It feels harsh, almost violent. Curator: Daumier was, in many ways, the people's artist. He understood social dynamics and wasn't afraid to critique them. During this period, Daumier frequently turned his satirical eye to the petty bourgeois and the criminal underworld of Paris. He initially began his career creating biting lithographs which satirized the French bourgeoise for journals like Le Charivari, which helped fuel and develop political movements. Editor: And you see that commentary reflected in the bodies – the vulnerability of the victim on the ground, the aggressor looming over him. Note the hat near the victim, almost a symbol of the middle class from whom it was taken by force. How do you see that socio-political critique unfolding here? Curator: This image belongs to a broader print series entitled *Souvenirs d’artistes,* suggesting the life and memories of an artist, though the image is still of violence and brigandry. Daumier also likely saw himself in the poor soul on the ground, in many ways forced to create work in return for a meager paycheck. Editor: Exactly! We have to situate Daumier within this specific historical moment. What were the conditions that made such stark social disparities, such everyday violence, so visible, so inescapable? Who benefited, and who suffered? The print becomes more than just art; it’s a piece of historical evidence of life at that time, and he’s showing the price he, too, had to pay to survive in society. Curator: And while his art was born of these tumultuous social currents, its resonance remains. There's a timeless quality to its social commentary, making it all the more accessible. This intersection of class, morality, and the sheer struggle to survive resonates across time, and allows us to see past our time. Editor: Yes, by looking back at what Daumier saw in his moment in history, we can find so many of our own present problems and issues to examine. These works ask not just what things were, but rather how they got that way and whether that’s how we’d like them to continue.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.