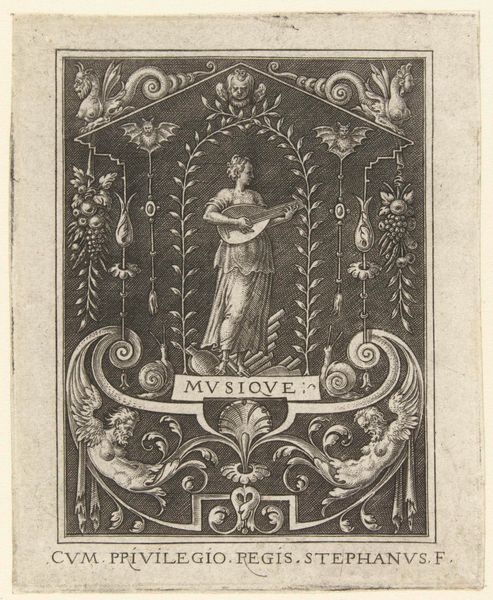

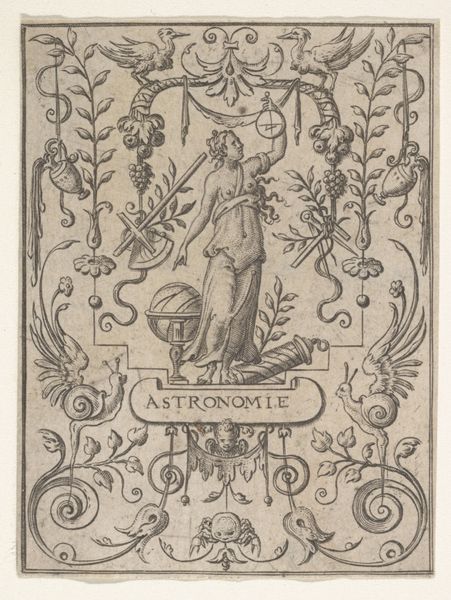

Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

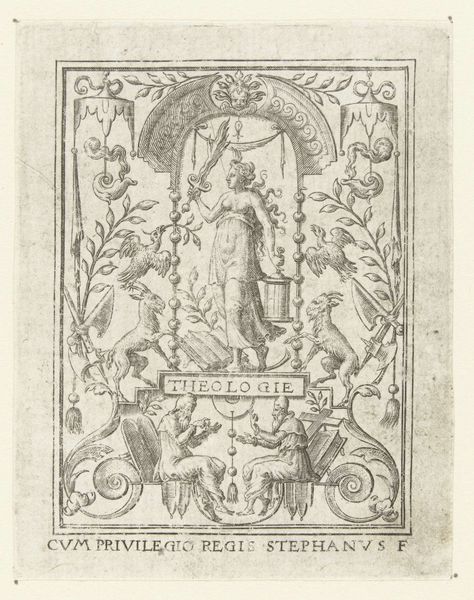

Curator: Before us, we have "Fysica," an engraving made with pen, dating back to the years 1528 to 1583, crafted by Etienne Delaune, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It is exquisitely detailed. The line work is delicate, yet there's a profound sense of density to the whole composition. Editor: It feels ornate, yet restrained by its very order. I am immediately struck by the symmetrical composition. There's a very definite hierarchy established with the central figure. Curator: Yes, a female figure personifying Physics. She stands on a pedestal inscribed with her name, holding a vessel, perhaps an alchemical flask. Consider what Physics represented then. Not just the study of the natural world, but also the pursuit of hidden knowledge, often linked to alchemy. Notice, the implements of alchemy—the mortar and pestle. Dogs flanking it; do they represent fidelity, or something else? Editor: Fidelity, maybe caution? Dogs can be quite intuitive. There’s definitely a symbolic program operating here. What about the architectural framing of foliage and fantastical birds perched above? Curator: Ah, that’s classic Renaissance symbolism! The birds could represent intellectual aspiration or even the transformation sought through alchemical processes. The snail creeping below the bird. Even this juxtaposition carries weight: aspiration grounded by the slow, deliberate work required for real knowledge. The roses signify beauty of physics, and roses are a gift to scientists by the art in that epoch. The architectural flourishes could reference knowledge is not something from an amorphous existence. Editor: I like the balance between naturalistic details, such as the botanicals framing the central image, and the more stylized, allegorical figures. How would this engraving have functioned in its time? Curator: Prints like this circulated widely, acting as visual emblems of knowledge. They could have been collected by scholars, artists, or even used as models for other works. “Fysica,” in essence, became a portable idea, a concentrated symbol of the era's fascination with science and the natural world. It has stood the test of time, hasn't it? Editor: Indeed. Analyzing it today, we rediscover a visual record and echoes of lost epistemologies. The interplay of lines and symbols is remarkable; even now, you can unravel deeper contexts just by studying it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.